Five places in Yorkshire to assess key geological hazards

A field trip to Yorkshire has helped our data products team improve their output.

21/12/2022 By BGS Press

In July 2022, the BGS Hazard Products team visited Yorkshire to assess some key geological hazards. The trip was an opportunity for the team to gain insight into the natural processes and geological features that underpin many of the digital data products they develop.

The team has a diverse skill set, from expertise in Python coding and GIS analysis to engaging with stakeholders and developing business relationships with partners and clients. This melting pot of skills allowed the team to consider geological hazards and potential solutions from a unique perspective and prompted useful discussions around translating BGS science into user-oriented digital hazard solutions as well as the quality and availability of input data.

The team spent two days in the field studying a range of geological hazards in action and considered the strengths and limitations of existing BGS geohazard data products to determine areas for future development.

Sutton Bank

Sutton Bank is a near-vertical, around 140 m-high cliff in Jurassic strata representing about 60 million years of geological time. During the last ice age, about 20 thousand years ago, a lobe of ice extended southwards in this lowland area between the North York Moors and the Pennines. As the ice flowed along the western edge of the moors, it gouged out the soft underlying rocks of the Lower Jurassic, leaving the escarpment you see today.

The hazard products team atop Sutton Bank discussing the glacial history of the Vale of York. BGS © UKRI.

Panorama from Sutton Bank viewpoint looking west over the Vale of York. Photo © Chris Heaton (cc-by-sa/2.0).

The clifftop panorama showcases a complex lowland landscape underlain by a mixture of superficial deposits and bedrock. As the ice melted and retreated, it deposited till and outwash deposits, which shaped the landscape we see from the viewpoint today. For example, Gormire Lake, located just below the escarpment at Sutton Bank, formed as a result of glacial deposits blocking drainage channels and trapping water behind them.

Sutton Bank National Park Centre is situated at the top of the escarpment, with parking, visitor centre, toilets and café. A short walk leads to a viewpoint with a panoramic view across the previously glaciated vale.

This location was really useful to visualise the landscape of the area and understand how glacial periods in Earth’s history had imprinted on this landscape. It provided useful context for the field sites to come.

Jenny Richardson.

Relevant data products

Sneck Yate

Continuing northwards along Cleveland Road from the visitors centre we reach Sneck Yate. Parking is located in a small gravel layby from where it is a short walk over the top of the escarpment to view cambering features.

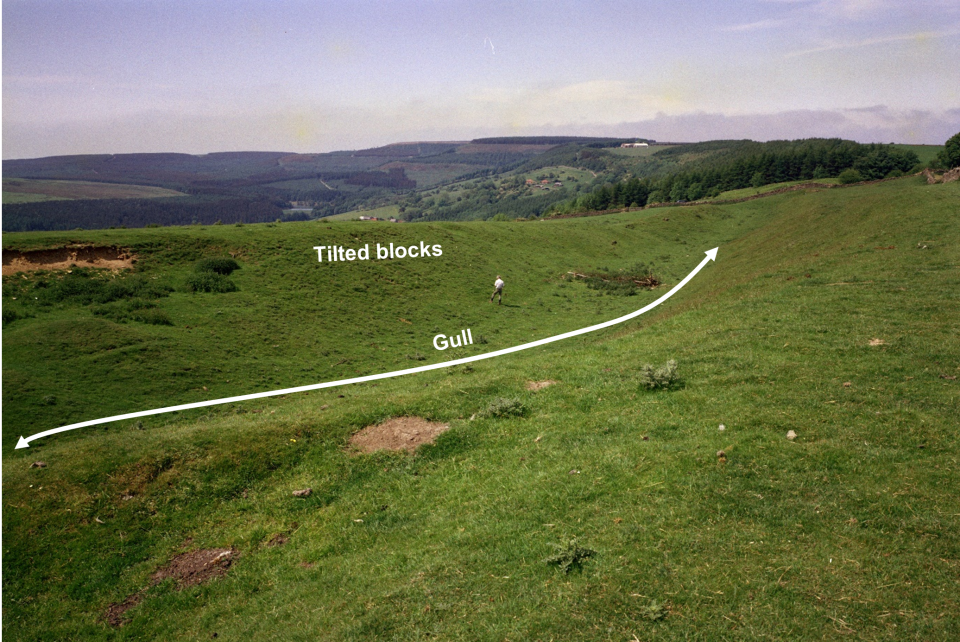

Annotated view of cambering features at Sneck Yate. BGS © UKRI.

The geology at this location comprises the same Jurassic strata as the previous site and this sequence of the Lower Calcareous Grit Formation and the Hambleton Oolite Member overlying the softer Oxford Clay Formation has created a geohazard called cambering.

Cambering involves large-scale stretching, tilting or rotation of more competent blocks of rock over less competent strata, in this case the Oxford Clay Formation. This tilting can result in discontinuities known as gulls opening up parallel to the valley axis, which can range in width from millimetres to tens of metres and may be sediment filled or not even propagate to the surface.

Cambering and associated features such as gulls and valley bulging are all responses to stress relief or ‘unloading’, which results from rapid incision or erosion of the landscape in conjunction with gravitational forces. It is often associated with glacial erosion and retreat.

This site helps us to better understand the processes associated with permafrost, Quaternary conditions and rates of landscape evolution. Improved understanding also informs planning for ground engineering projects.

- More detailed explanation of cambering and associated geological features

The size and scale of these features can impact significantly on engineering projects, for example, evaluation of clay disturbance as a consequence of valley bulging was critical to the construction of the Empingham dam at Rutland Water and the upper dams of the Derwent Valley. Cambering is not explicitly defined in our current data products and visiting this site prompted useful discussions on the feasibility to improve this.

Russell Lawley.

Relevant data products

Hawnby

Bridge over River Rye at Hawnby during reconstruction following flood damage in June 2005. © Colin Grice (cc-by-sa/2.0).

From the top of the escarpment the team dropped down into Hawnby village. En route, we noted the steep slopes and landslide events associated with particular geological horizons. Here, an impermeable clay layer forces groundwater to the surface where it emerges as springs and in several cases has initiated landslides in the overlying superficial deposits.

Hawnby lies in Rye Dale on the northern bank of the River Rye. River erosion, flooding and water availability can all be considered risks here. The bridge at Hawnby forms a narrow pinch-point in the valley and carries key utilities infrastructure over the River Rye. From 19 to 20 June 2005 there was a major storm event and flooding devastated the area. Damage included the complete destruction of the bridge, removing access to the village and further impacting the community through the loss of utilities.

It is particularly important to understand the geological constraints and potential for flood events, especially in changing climate conditions where storms are more likely to become more frequent and more intense. When the bridge was rebuilt, design improvements were made to allow water to flow across the bridge and road in an effort to prevent the constriction of river flow and associated erosion in future flood events.

Understanding the capacity of the floodplain, the erosion potential of the sediments and the additional influences such as extra water input into the system from springs can hugely help catchment planning and effective adaptation.

Henry Holbrook.

Relevant data products

Holbeck Hall, Scarborough

Large rotational landslide at Holbeck Hall, Scarborough. BGS © UKRI.

Defended toe of Holbeck Hall landslide deposit. Photo © Paul Glazzard (cc-by-sa/2.0).

South of Scarborough is the site of the former Holbeck Hall Hotel, which was destroyed by a landslide between 3 and 5 June 1993.

The Holbeck Hall site is underlain by till deposits overlying the Long Nab Member at the top of the cliff, with the Scarborough Formation cropping out on the foreshore and creating a wave-cut platform. This rotational landslide involving about one million tonnes of glacial till cut back the 60 m-high cliff and flowed out across the beach to form a semicircular promontory 200 m wide projecting 135 m outward from the foot of the cliff. This was rotational landslide that degraded to a mud or debris flow and covered the rocks of the wave-cut platform.

The first signs of movement on the cliff were seen six weeks before the main failure, when cracks developed in the tarmac surface of footpaths running across the cliffs.

The likely cause of the landslide was a combination of:

- intense rainfall in the prior two months

- poor drainage of the slope

- high pore-water pressure in the slope

- susceptible superficial geology

Coastal defences have since been installed to protect the toe of the slope from further erosion and pore waters are monitored regularly.

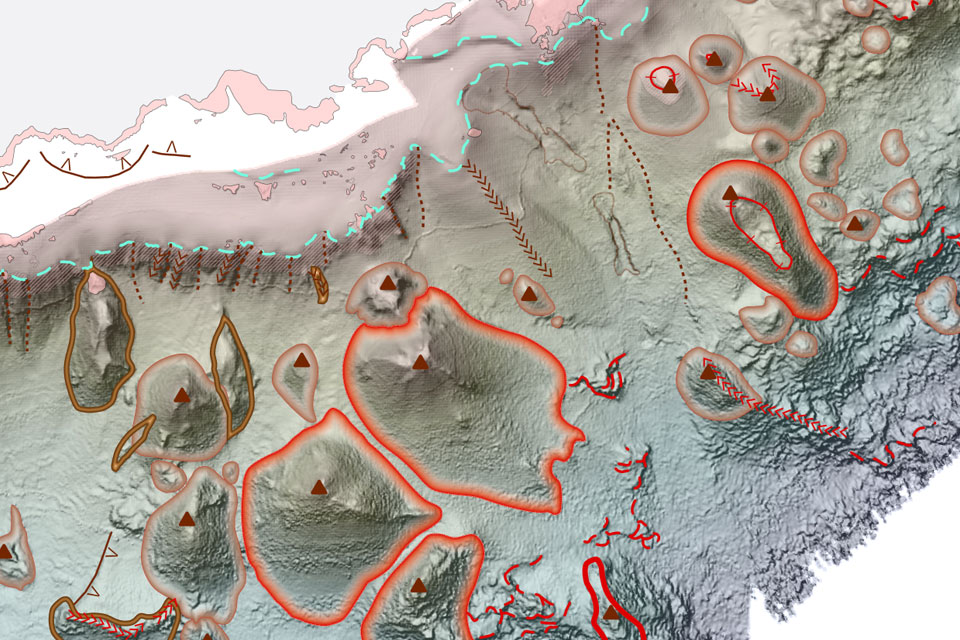

We have been investigating using remote sensing terrain data to identify historic coastal mass movement deposits and it was helpful to observe the form and terrain characteristics of this large scale landslide. Landslide morphology is especially complex at the coast where wave action is also an issue.

Sophie Taylor.

Relevant data products

Danes Dyke, near Flamborough

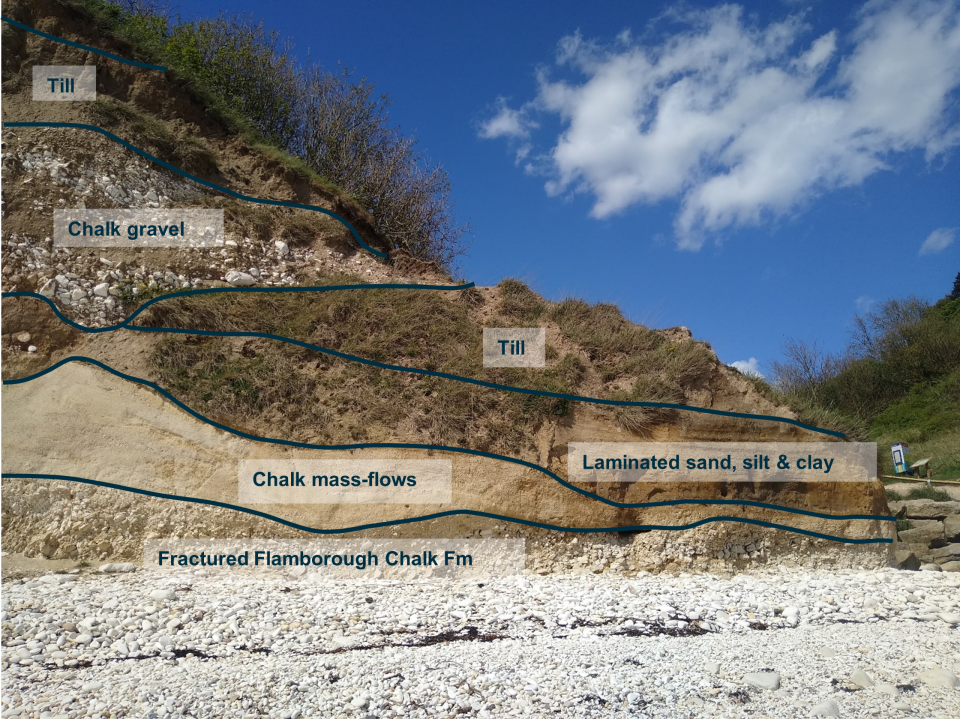

Annotated sequence of superficial deposits above chalk bedrock at Danes Dyke. BGS © UKRI.

Danes Dyke lies on the southern coast of the Flamborough Head peninsula. It consists of a deep, wooded valley running north–south towards the coast.

The steep ravine is a palaeo-valley about 150 m wide and filled with a complex succession of periglacial, glacial and aeolian sediments. The chalk is folded and faulted with structures visible in the foreshore at low tide. Periglacial weathering was likely focused here due to the presence of faults and evidence for periglacial fractured chalk and rubbly chalk gravel can be seen in the cliffs at the mouth of the ravine. These gravels are overlain by till deposited by a North Sea lobe of the last British–Irish ice sheet that emanated from the Grampian Highlands of Scotland and flowed southwards over which is now the floor of the North Sea.

It is important to understand the nature of the boundary between the chalk bedrock and overlying superficial deposits as well as the properties of the different lithologies. Fracturing and weathering also cause weaknesses in the rock, making them more susceptible to failure.

The typically uneven boundary between chalk and till, differential rates of weathering, and chalk dissolution can have impacts on building foundation design, underground utilities and infrastructure projects. Where these features occur inland, they’re often unseen, so being able to visualise this boundary and erosion features at the coast is a helpful exercise when considering measures to mitigate against associated issues

Clive Cartwright.

Relevant data products

Relative topics

Related news

BGS scientists join international expedition off the coast of New England

20/05/2025

Latest IODP research project investigates freshened water under the ocean floor.

New seabed geology maps to enable long term conservation around Ascension Island

01/04/2025

BGS deliver the first marine geology and habitat maps for one of the world’s largest marine protected areas.

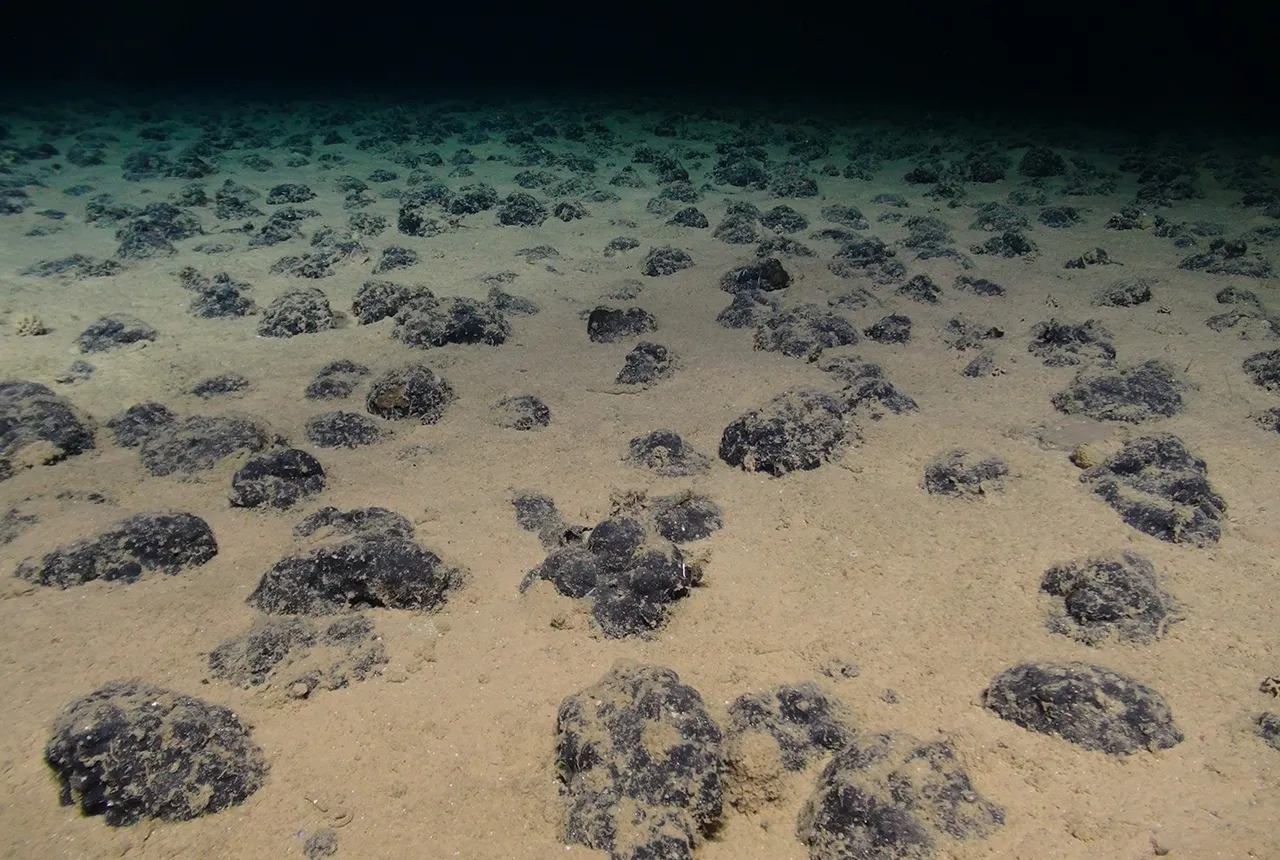

New study reveals long-term effects of deep-sea mining and first signs of biological recovery

27/03/2025

BGS geologists were involved in new study revealing the long-term effects of seabed mining tracks, 44 years after deep-sea trials in the Pacific Ocean.

Seabed geology data: results from stakeholder consultation

31/01/2025

BGS collected valuable stakeholder feedback as part of a new Crown Estate-led initiative to improve understanding of national-scale seabed geology requirements.

UKGravelBarriers

Increasing our understanding and modeling capabilities of gravel beach and barrier dynamics.

Monitoring coastal change from space

BGS is helping to develop applications that detect and track coastal erosion and accretion from space to inform coastal management plans.

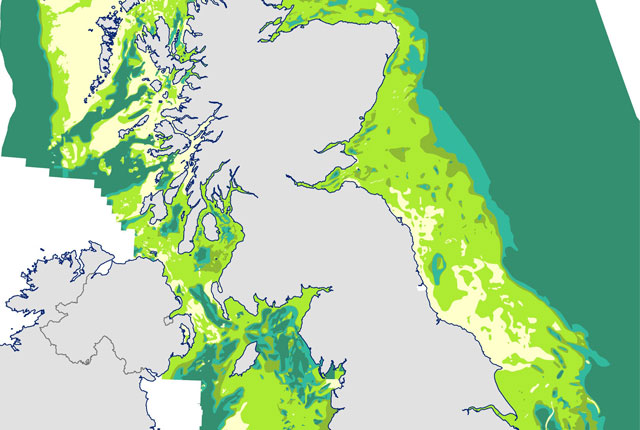

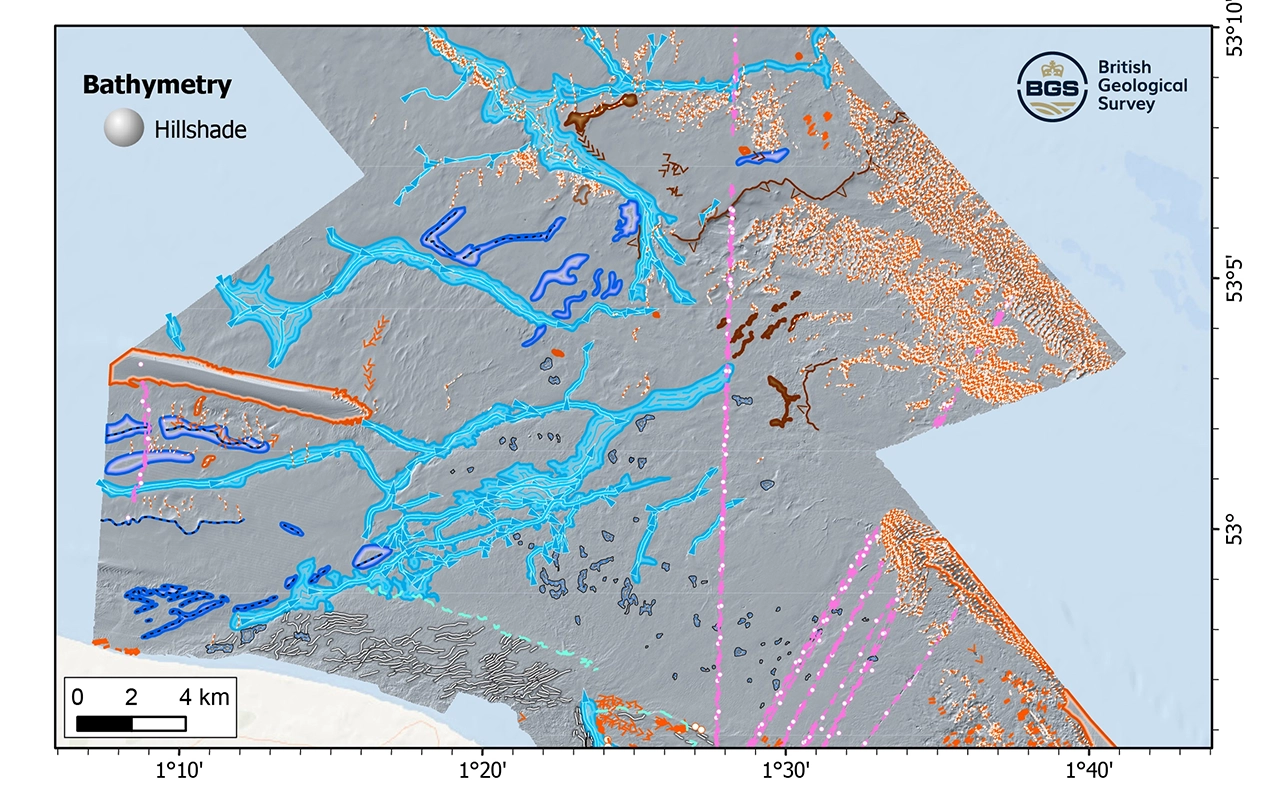

New research reveals the secrets of the seabed off the East Anglian coast

11/07/2024

New geological map will help in the hunt for new renewable energy opportunities whilst protecting delicate marine ecosystems.

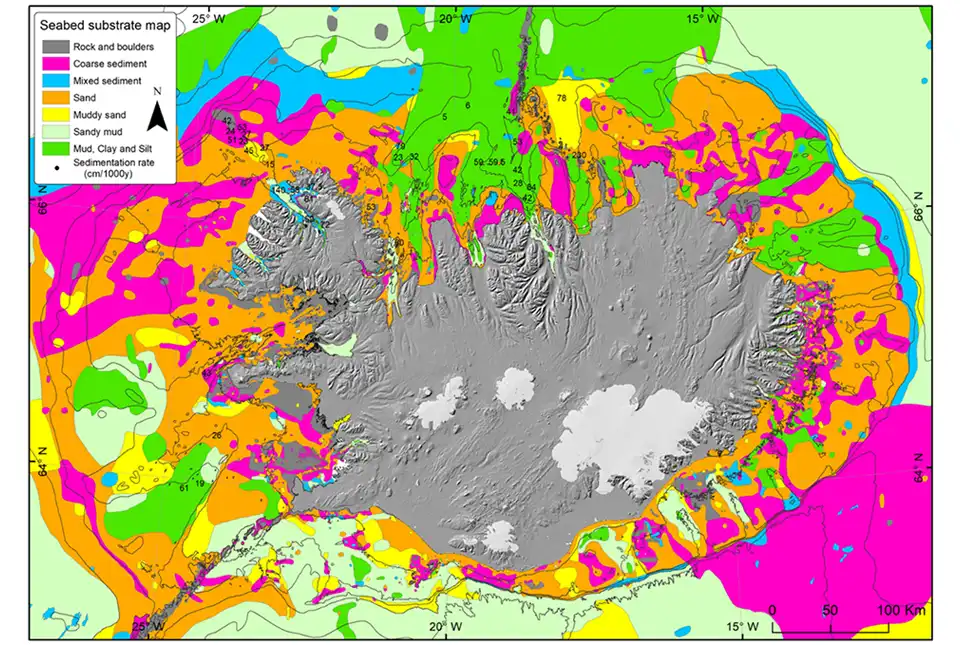

BGS awarded research grant to support potential offshore wind development in Iceland

13/05/2024

BGS has been awarded the NERC-Arctic grant for a collaboration project with Iceland GeoSurvey.

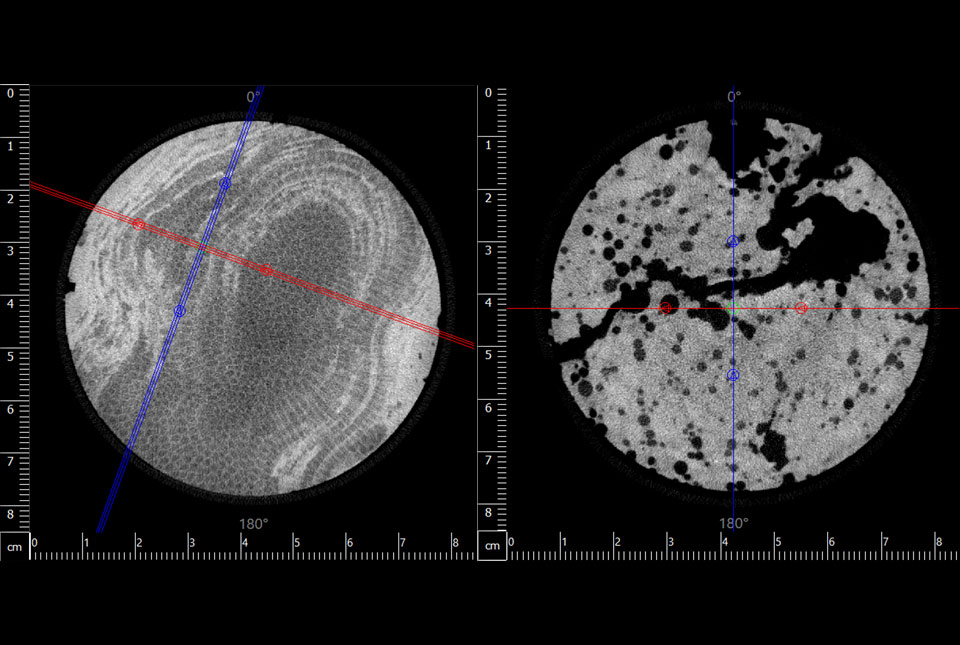

Largest CT core scan completed at the BGS Core Scanning Facility

09/05/2024

BGS has completed its largest CT core scan project to date, with around 400 m of core imaged for the IODP Drowned Reefs project.

Scientists produce first record of environmental data off coast of Hawai’i

01/03/2024

An international team of researchers, including BGS geoscientists, have succeeded in acquiring a continuous record of environmental data using fossilised coral from Hawai’i.