Burrow-detecting devices could protect flood defences

BGS scientists have trialled a new way of detecting animal burrows in clay flood embankments.

23/01/2024 By BGS Press

Badgers and other burrowing animals can weaken the structural integrity of flood defences. New devices being trialled by BGS use electrical resistivity to detect and map burrows in order to help find solutions.

The UK has over 7500 km of embankments along its rivers and streams, protecting the communities and infrastructure behind them. But these vital flood defences can be weakened when burrowing animals like badgers, rabbits and now beavers move in and weaken their structural integrity. When that happens, embankments are more likely to fail during a flood and leave the locations they protect vulnerable to flooding.

Electrical resistivity tomography survey over the badger sett. The burrow entrances are hidden in the long vegetation and extend to the fence on the left-hand side. BGS © UKRI.

Using electrical resistance to detect burrows

Until now, regulators and landowners have had no way to know where the badger burrows go underground or if the burrows have caused significant damage to the flood embankment.

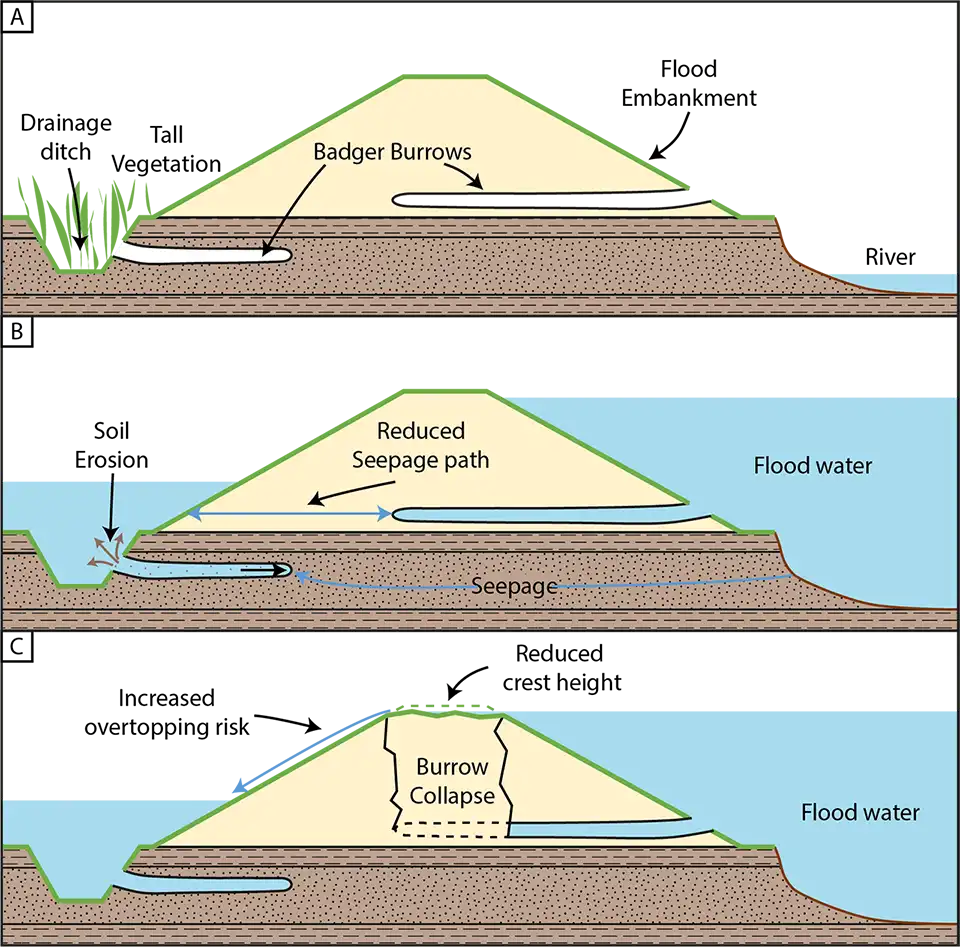

Badgers can damage flood embankments by digging burrows into them. During floods, these burrows may let water through the embankment or collapse, reducing the height of the embankment, which may allow water over the top. BGS © UKRI.

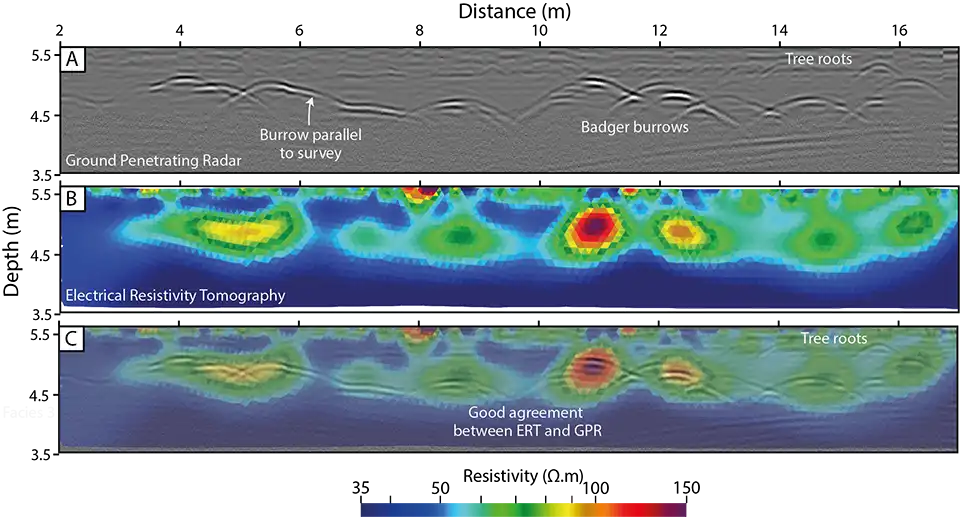

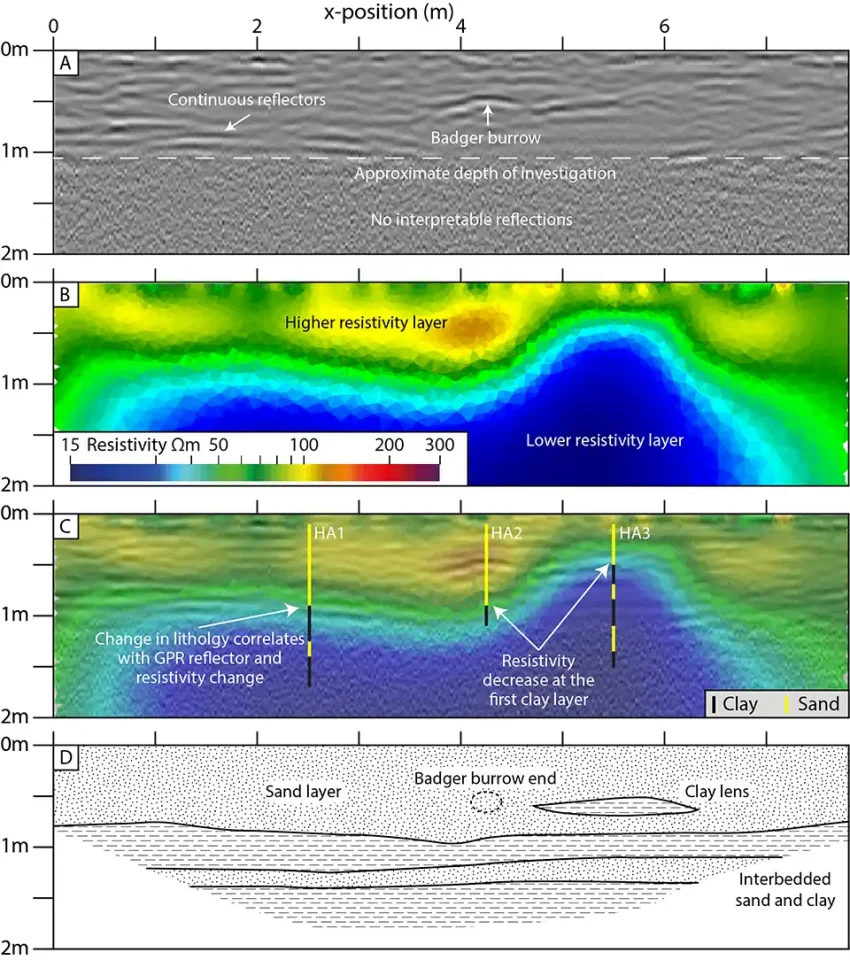

Geophysical image of a slice through a badger sett at Wistow, near Cawood, using (A) ground penetrating radar and (B) electrical resistivity tomography. The geophysical images are interpreted with borehole data (C), showing the badgers have dug a single tunnel through the sand layer (D). BGS © UKRI.

Adrian White, a geophysicist from BGS, and his colleagues trialled a new technique on an embankment on the River Ouse, North Yorkshire, which protects Cawood, a village of 1500 people, from flooding.

There have been several cases where badgers and other animals have caused embankments to fail, and it can happen very quickly if the burrows are in critical areas of the embankment.

Badgers are a protected species, so once they’ve been spotted at an embankment it can take months to deal with the problem. The burrows must be found, the badgers moved on, and then the site has to be repaired. And there’s always the risk they could move 100 m down the road and find a new embankment to burrow into.

The whole process takes months, is expensive and labour intensive, but we only find out if the burrows have damaged the embankment once the repair work starts.

Adrian White, BGS Geophysicist.

Advantage for clay embankments

Currently, ground penetrating radar (GPR) is used by scientists and consultants to map underground voids.

We trialled electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) on the embankment. Similar to GPR it’s not invasive; we just insert electrodes into the ground that reach about 10 cm into the soil.

ERT works by passing an electrical current between the electrodes inserted into the ground and measuring the voltage difference between other electrodes. It’s a widely used technique and is already used to map subsurface geology and identify archaeological structures. The system allows the scientists to map the electrical resistance of the soil and, as the burrows are filled with air, which is very electrically resistive, they show up as resistive anomalies in ERT surveys.

The ERT could detect badger burrows up to 1.5 m deep in the clay and map the structure of the badger sett, which had multiple entrances. It clearly outperformed the GPR, which doesn’t work very well on clay-rich ground, because the clay absorbs the radar waves.

This is great news for the agencies and managers in charge of monitoring and repairing flood embankments: it can quickly assess stability, reduce repair costs and minimise the likelihood of unexpected failures during flood events.

And, critically, it doesn’t disturb the animals.

Adrian White.

The UK’s flood embankment inventory

The UK has built flood embankments for hundreds of years and they play a critical role in our flood defences in both rural and urban areas. In England and Wales, the Environment Agency maintains most, but landowners and farmers maintain some informal embankments.

Burrowing by animals like badgers rapidly change how well an embankment can hold a flood back. One day there can be nothing and the next, a whole load of tunnels. It’s a huge challenge and we must find better ways to mitigate the impact of our wildlife on what will be the last line of defence for some communities.

Recently, beavers have started to recolonise UK rivers, and it is hoped they will help reduce flooding. What is less well-known is that they are excellent burrowers. These burrows start below the water, so may undermine flood defences without us knowing they are there. We’ll need new techniques to find and map those too.

Adrian White.

More information

White, A, Wilkinson, P, Boyd, J, Wookey, J, Kendall, J M, Binley, A, Grossey, T, and Chambers, J. 2023. Combined electrical resistivity tomography and ground penetrating radar to map Eurasian badger (Meles meles) burrows in clay-rich flood embankments (levees). Engineering Geology, Vol. 323, 107198. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2023.107198

Morris, M, Dyer, M, and Smith, P. 2007. Management of Flood Embankments: a good practice review. R&D Technical Report, FD2411/TR1. (London, UK: Defra/Environment Agency.)

Rickard, C E . 2010. Chapter 9 Floodwalls and flood embankments. In Fluvial Design Guide. Ackers, J C, Rickard, C J, and Gill, D S. (London, UK: Defra.)

Relative topics

Related news

New collaboration aims to improve availability of real-time hazard impact data

19/06/2025

BGS has signed a memorandum of understanding with FloodTags to collaborate on the use of large language models to improve real-time monitoring of geological hazards and their impacts.

BGS Groundwater Flooding Susceptibility: helping mitigate one of the UK’s most costly hazards

25/09/2024

Groundwater flooding accounts for an estimated £530 million in damages per year; geoscientific data can help to minimise its impact.

New £38 million project to reduce the impact of floods and droughts

02/09/2024

BGS will take a leading role in efforts to better predict the location and effects of extreme weather events.

Spotlight on BGS coastal erosion data

18/07/2024

BGS GeoCoast data can support researchers and practitioners facing coastal erosion adaptation challenges along our coastline.

Burrow-detecting devices could protect flood defences

23/01/2024

BGS scientists have trialled a new way of detecting animal burrows in clay flood embankments.

Natural flood management: is geology more important than trees?

23/11/2023

Looking at innovative ways of creating resilience to flooding hazards with natural flood management.

River erosion: the forgotten hazard of flooding

03/08/2022

Impacts from flood events can be widespread, long-lasting and extremely costly. The UK Government and environmental protection agencies continue to invest heavily in mitigation measures, as well as trying to predict which areas are most at risk.

GeoScour dataset launch event

Event on 08/09/2022

BGS Product Development invites you to the launch of our newly updated dataset, GeoScour.

Groundwater level forecasting

BGS delivers probabilistic forecasts of groundwater levels across the UK’s principal aquifers to provide a range of services that build national resilience to groundwater extremes.

BGS to deliver three-year groundwater flood forecasting service to support emergency response to flooding

29/11/2021

BGS is delivering a national-scale early warning system for groundwater flooding, alongside the Environment Agency and the Met Office.

Building with nature and geology to protect against flooding

30/04/2021

Discover how BGS is working alongside partners to investigate the effectiveness of natural flood management initiatives and mitigate the threat of flooding.