Building with nature and geology to protect against flooding

Discover how BGS is working alongside partners to investigate the effectiveness of natural flood management initiatives and mitigate the threat of flooding.

30/04/2021

Beaver dams instead of concrete dams, re-meandering instead of dredging, floodplain parks and wetlands instead of concrete flood walls — who wouldn’t want to build with nature? For many years we have been doing just the opposite, fighting against the environment, attempting to conquer nature. The ecological impacts of these ‘hard engineering’ solutions are many, from trapping sediment and disrupting fish migrations to starving wetlands of water, turning them from greenhouse gas sinks into greenhouse gas sources.

Flooding and climate change

The aim of flood risk management is to protect people and property from the devastating impact of flooding. While a concrete wall may not add to the aesthetics or ecology of a river bank, it is usually a very effective means of achieving this aim. We need effective solutions because the risk of flooding is increasing in the UK, as the climate becomes wetter. In England and Wales, one study found that climate change has increased the risk of floods by at least 20 per cent and possibly by as much as 90 per cent. The latest Met Office climate projections show that winters will continue to become wetter in the UK throughout the 21st century.

Natural flood risk management

The UK’s river landscapes bear little resemblance to natural landscapes. We have created hard surfaces perfect for rapid runoff, built homes and roads on floodplains and straightened, dredged and built embankments on rivers, speeding up river flow, reducing infiltration and exacerbating downstream flooding. Natural flood risk management (NFM) aims to reduce flood risk by slowing the flow of water through the landscape. Native woodland, retention ponds and woody debris dams will all help to provide storage for water in the headwaters and, lower down in the catchment, floodplains will be restored. In doing so, NFM re-establishes the natural functions of river catchments, providing habitat for a diverse wildlife. It sounds perfect, doesn’t it? There is just one caveat — we are not sure how well it actually works.

An example of natural flood management slowing the flow of water through the landscape. Source: Leo Peskett.

There are now over 90 NFM projects in the UK, with around 15 active schemes. There have also been developments in policy to aid the implementation of NFM, such as SEPA’s production of an NFM handbook in 2016 and Defra’s 2017 review of the evidence base and production of guidance. Despite the increase in NFM implementation, monitoring and quantitative assessment of schemes remains low and evidence of effectiveness is still limited. However, investment in scientific research on NFM is on the rise and with it we expect find out what types of NFM work best and where.

BGS and flooding

Why is BGS interested in surface water flooding? What does NFM have to do with geology? BGS’s work on monitoring the effectiveness of NFM has focused on two areas: the Eddleston catchment of the River Tweed and the West Thames.

Eddleston

The Eddleston catchment is one of the most intensively monitored NFM observatories in the UK and BGS has been involved with the project since its inception. So far, we have found that:

- older and mixed woodland can absorb water a lot more quickly than plantation woodland

- narrow forest strips planted to prevent rapid hillslope runoff provide little subsurface storage during flood events

- understanding geology provides key insights into the hydrological behaviour of floodplains

Most recently, and perhaps most importantly, we have found that geology and soil type have a greater influence on rapid surface runoff than plantation forest cover.

West Thames

In the West Thames, BGS is working with the University of Reading and JBA Consulting, among other partners, to investigate the effectiveness of NFM in lowland permeable (chalk and limestone) catchments. We are studying measures such as crop choice, tillage practices and tree planting for their ability to increase evaporation and infiltration of water into chalk and limestone aquifers. The hope is that, by increasing infiltration, surface runoff and flood risk are reduced.

BGS’s role

But this water that infiltrates into the ground does not simply disappear. It is BGS’s job to understand what happens to this water once it has entered the bedrock: could groundwater levels rise, increasing the risk of groundwater flooding? Inversely, an increase in evaporation could lead to falling groundwater levels and water shortage in chalk aquifers, a major drinking water source in southeast England.

The move towards NFM seems like an obvious choice, given the co-benefits provided for wildlife and the problems associated with traditional flood measures. However, it is imperative that these schemes continue to be monitored and assessed for their effectiveness to make sure that their primary purpose — the protection of people and property from the economic and societal impact of flooding — is met.

And what does geology have to do with NFM? We need to ensure we are planting the right species of tree on the most suitable underlying geology.

About the author

Sarah Collins

Groundwater modeller

Relative topics

Latest blogs

AI and Earth observation: BGS visits the European Space Agency

02/07/2025

The newest artificial intelligence for earth science: how ESA and NASA are using AI to understand our planet.

Geology sans frontières

24/04/2025

Geology doesn’t stop at international borders, so BGS is working with neighbouring geological surveys and research institutes to solve common problems with the geology they share.

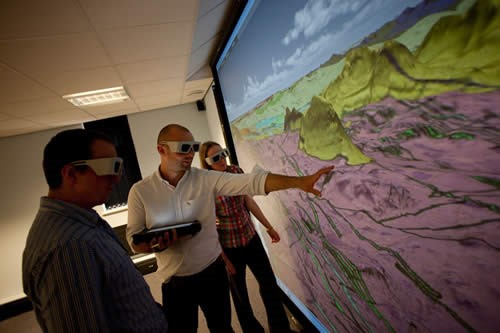

Celebrating 20 years of virtual reality innovation at BGS

08/04/2025

Twenty years after its installation, BGS Visualisation Systems lead Bruce Napier reflects on our cutting-edge virtual reality suite and looks forward to new possibilities.

Exploring Scotland’s hidden energy potential with geology and geophysics: fieldwork in the Cairngorms

31/03/2025

BUFI student Innes Campbell discusses his research on Scotland’s radiothermal granites and how a fieldtrip with BGS helped further explore the subject.

Could underground disposal of carbon dioxide help to reduce India’s emissions?

28/01/2025

BGS geologists have partnered with research institutes in India to explore the potential for carbon capture and storage, with an emphasis on storage.

Carbon and oxygen isotope analysis of carbonates and the development of new reference materials

18/12/2024

Dr Charlotte Hipkiss and Kotryna Savickaite explore the importance of standard analysis when testing carbon and oxygen samples.

Studying oxygen isotopes in sediments from Rutland Water Nature Reserve

20/11/2024

Chris Bengt visited Rutland Water as part of a project to determine human impact and environmental change in lake sediments.

Celebrating 25 years of technical excellence at the BGS Inorganic Geochemistry Facility

08/11/2024

The ISO/IEC 17025 accreditation is evidence of technical excellence and reliability, and a mark of quality assurance.

Electromagnetic geophysics in Japan: a conference experience

23/10/2024

Juliane Huebert took in the fascinating sights of Beppu, Japan, while at a geophysics conference that uses electromagnetic fields to look deep into the Earth and beyond.

Exploring the role of stable isotope geochemistry in nuclear forensics

09/10/2024

Paulina Baranowska introduces her PhD research investigating the use of oxygen isotopes as a nuclear forensic signature.

BGS collaborates with Icelandic colleagues to assess windfarm suitability

03/10/2024

Iceland’s offshore geology, geomorphology and climate present all the elements required for renewable energy resources.

Mining sand sustainably in The Gambia

17/09/2024

BGS geologists Tom Bide and Clive Mitchell travelled to The Gambia as part of our ongoing work aiming to reduce the impact of sand mining.