BGS collaborates with Icelandic colleagues to assess windfarm suitability

Iceland’s offshore geology, geomorphology and climate present all the elements required for renewable energy resources.

03/10/2024 By BGS Press

BGS and the Icelandic Geological Survey (ÍSOR) have been awarded an Arctic Office NERC grant to assess Iceland’s offshore geological and geomorphological landscapes for the suitability of windfarms. The grant enables BGS scientists to share their experience in offshore mapping, as well as working with wind developments.

Iceland fulfils its primary energy consumption with around 100 per cent renewable energy, via geothermal and hydro energy. Nowadays, there is a strong motivation to increase the country’s energy mix and energy security via wind power. Geology underpins the appropriate placement and foundation design for wind turbine structures. The NERC grant, which is supported by the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, aims to facilitate knowledge sharing between BGS and ÍSOR about the geological classification of the seabed and subsurface, as well as the potential impacts on foundation design.

To help facilitate this partnership, Anett Blischke, a senior geoscientist at ÍSOR, led a week-long field trip in Iceland. Participants from BGS included Nicola Dakin, Andrew Finlayson, Dayton Dove and Duncan Stevens, who were joined by ISOR’s Árni Magnússon, Steinunn Hauksdóttir and Ögmundur Erlendsson, alongside Sigurður Friðleifsson from the National Energy Authority of Iceland (Orkustofnun).

Visiting Iceland presented a fantastic opportunity to see excellent analogue sites onshore that are often present in the UK’s offshore environment, such as glacial landforms and deposits. The field visits allowed us to discuss these sites, including the glacial moraine complex of Skeiðarársandur, how geoscience fits into the offshore wind development process in Iceland and its opportunities and challenges.

The moraine complex at Skeiðarársandur showing more than 50 m topography with boulders and coarse to fine sediments. At the right are BGS’s Dayton Dove and Duncan Steven, who are both about 1.83 m tall, for scale! Extensive sedimentary systems like Skeiðarársandur are sourced and shaped by the advance and retreat of glaciers over millennia. These processes have influenced the large volumes and types of sediment found where the land meets the sea and extends into the offshore environment. BGS © UKRI.

Visit to the British Embassy

The team was also invited to the British Embassy in Reykjavík to discuss the goals of the project. Embassy staff were eager to hear about the project goals and future collaborations around geology and renewables. During the visit and in her role as task lead of the Geological Service for Europe’s ‘Optimised windfarm siting’ work package, Nicola Dakin highlighted the benefits of the first deliverable to the European Commission: using the new ‘Geo-Assessment Matrix’, which will develop the first draft geological complexity maps offshore Iceland and European waters. Utilising existing datasets, such as EMODnet Geology, the maps aim to serve as a first-pass assessment showing areas that have low to high geological complexity. The maps will also highlight areas that require new data acquisition where the geology is unknown.

Fieldwork

The team then travelled east to Landsvirkjun, the state-owned energy utility company, at Búrfell, which is an onshore wind turbine test site consisting of two turbines that have been in situ since 2012. Here, Landsvirkjun has been testing the development of onshore wind potential, using the powerful and persistent winds in the Icelandic highlands. Environmental impact assessments have been important to ensure that the effects on the area are minimised and a 200 MW windfarm has received development approval.

The field trip continued along south Iceland’s coastal ribbon, where the team observed active volcanic, tectonic, sedimentary and glacial processes, the effects of sea level changes, and geohazards. Such onshore analogues are critical to understanding the geological processes found in offshore environments. Starting in the west, at Stokkseyri, and travelling to Jökulsárlón (‘Diamond Beach’) in the east, the team visited a range of geological outcrops and sites highlighting the variety of tectonic, sedimentary and volcanic challenges.

South Iceland offers a variety of geological features that can be studied to better understand the offshore environment: variable topography, ancient lava flows and glacial landforms tens of metres high. Understanding depositional environments, such as those around Svínafellsjökull, is key to understanding their effects on sedimentology and any possible engineering implications in advance of foundation design and installation.

Svínafellsjökull. From left to right: Nicola Dakin (BGS); Anett Blischke (ÍSOR); Duncan Stevens (BGS); Dayton Dove (BGS); Andrew Finlayson (BGS). BGS © UKRI.

The final study location of Melasveit consists of an outcrop near Akranes, north-west of Reykjavík. The locality exposes ancient glaciotectonised sediments in a cliff section along the beach (Sigfúsdóttir et al., 2018). This cross-section is an excellent analogue to the lateral and vertical heterogeneity, and possible geotechnical impacts, of glaciotectonised sediments, which are also observed in windfarm sites the North Sea.

Melasveit, near Akranes. Glaciotectonised sediments in the beach cliff section. Right: Dayton Dove (BGS). BGS © UKRI.

The final, fortuitous and (naturally) most spectacular geological phenomenon was a visit to the fissure eruption that began during our visit on 22 August 2024 near the Blue Lagoon and the Svartsengi geothermal energy plant. Icelandic authorities closed the roads to protect people; however, the eruption and lava flows can be observed safely from the roadside.

Fissure eruption near Akranes, which started 22 August 2024. BGS © UKRI.

Future collaboration

Iceland is a country full of opportunity regarding offshore wind potential. The geohazards and geological constraints in the offshore environment require a full assessment to better understand the influence on foundation types and design. BGS openly welcomes ÍSOR and Orkustofnun for further workshops and continuing our collaboration in the future.

More information

Field guide

A detailed field guide summarising the visited sites is available online.

References

Sigfúsdóttir, T, Benediktsson, Í Ö, and Phillips, E. 2018. Active retreat of a Late Weichselian marine‐terminating glacier: an example from Melasveit, western Iceland. Boreas, Vol. 47(3), 813–836. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/bor.12306;

Relative topics

Related news

Goldilocks zones: ‘geological super regions’ set to drive annual £40 billion investment in jobs and economic growth

10/06/2025

Eight UK regions identified as ‘just right’ in terms of geological conditions to drive the country’s net zero energy ambitions.

BGS scientists join international expedition off the coast of New England

20/05/2025

Latest IODP research project investigates freshened water under the ocean floor.

New interactive map viewer reveals growing capacity and rare earth element content of UK wind farms

16/05/2025

BGS’s new tool highlights the development of wind energy installations over time, along with their magnet and rare earth content.

Latest mineral production statistics for 2019 to 2023 released

28/04/2025

More than 70 mineral commodities have been captured in the newly published volume of World Mineral Production.

Geology sans frontières

24/04/2025

Geology doesn’t stop at international borders, so BGS is working with neighbouring geological surveys and research institutes to solve common problems with the geology they share.

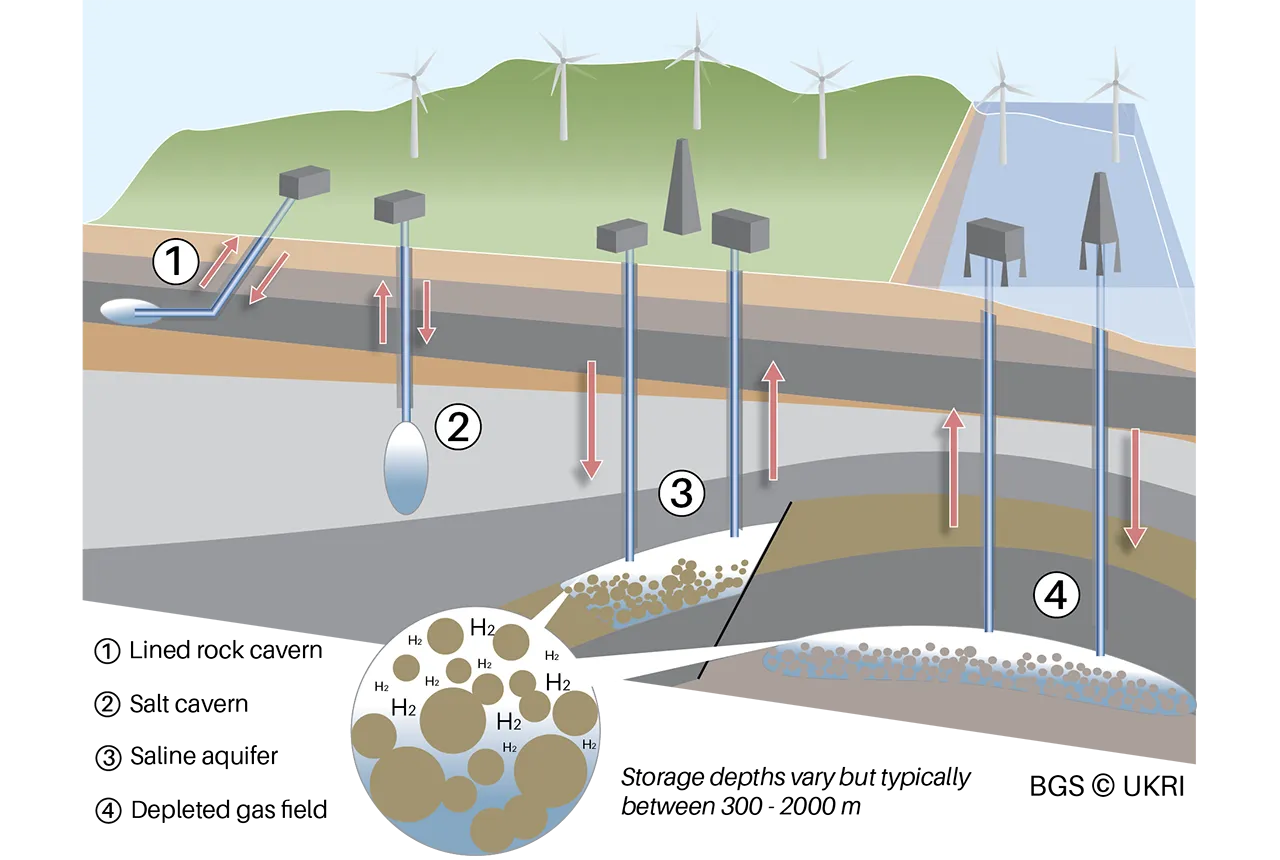

Making the case for underground hydrogen storage in the UK

03/04/2025

A new BGS science briefing note focuses on the potential of hydrogen storage to support the UK energy transition.

Exploring Scotland’s hidden energy potential with geology and geophysics: fieldwork in the Cairngorms

31/03/2025

BUFI student Innes Campbell discusses his research on Scotland’s radiothermal granites and how a fieldtrip with BGS helped further explore the subject.

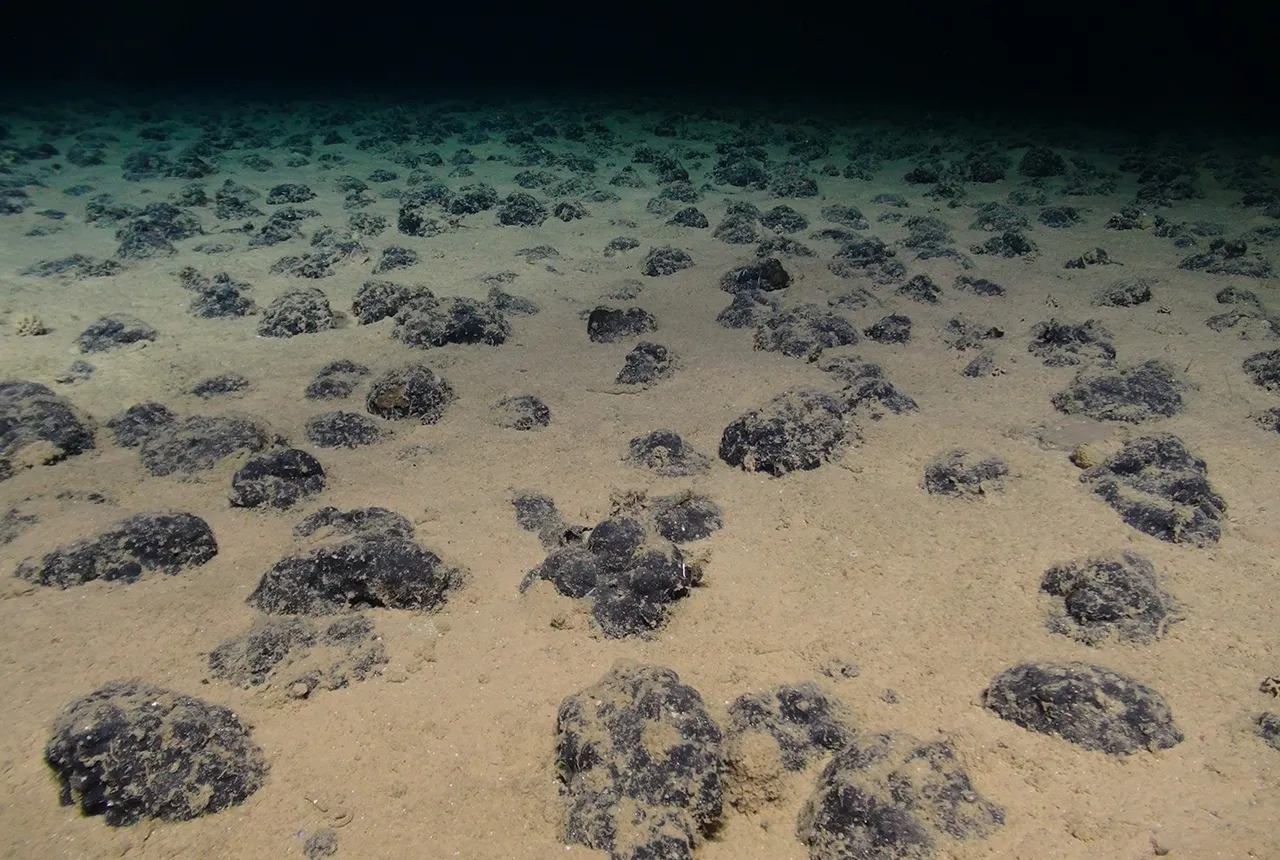

New study reveals long-term effects of deep-sea mining and first signs of biological recovery

27/03/2025

BGS geologists were involved in new study revealing the long-term effects of seabed mining tracks, 44 years after deep-sea trials in the Pacific Ocean.

BGS announces new director of its international geoscience programme

17/03/2025

Experienced international development research leader joins the organisation.

Future projections for mineral demand highlight vulnerabilities in UK supply chain

13/03/2025

New Government-commissioned studies reveal that the UK may require as much as 40 per cent of the global lithium supply to meet anticipated demand by 2030.

Presence of harmful chemicals found in water sources across southern Indian capital, study finds

10/03/2025

Research has revealed the urgent need for improved water quality in Bengaluru and other Indian cities.

Dr Kathryn Goodenough honoured with prestigious award from The Geological Society

27/02/2025

Dr Kathryn Goodenough has been awarded the Coke Medal, which recognises those who have made a significant contribution to science.