Building stones spotlight: the Sir Walter Scott Memorial 25 years after its conservation

BGS geologist, Luis Albornoz-Parra, discusses the iconic Edinburgh monument, the building stones used in its construction and the result (so far) of its conservation efforts.

29/04/2024

This magnificent, space-ship-like Victorian Gothic monument is a tribute to one of Scotland’s finest writers, Sir Walter Scott, and also happens to be one of my favourite stone-built structures.

This monument holds a special place in my heart. I first arrived in Edinburgh on my birthday, back in October 2000. As I stepped off the bus, this monument stood before me, black against the hazy grey backdrop of the Old Town. An instant confirmation that I was in the right place to fulfil my stone conservation dream.

Conservation work on this particular structure happened prior to my arrival in Edinburgh, however I have climbed the narrow 287-step spiral stair case to the top on many occasions to understand more about the author and the monument itself.

There is much to be learned from its 183-year history.

A masterpiece that came with a price beyond money

The Scott Monument is amongst the most important monuments in Edinburgh and possibly one of Scotland’s most significant. At 200 feet tall (almost 61 m), it is currently the second largest monument to a writer in the world. The monument’s design and construction (between 1840 and1844) were led by the talented joiner and self-taught architect, George Meikle Kemp, who anonymously entered the competition to design the monument. Tragically, he drowned in the Union Canal before the monument’s completion.

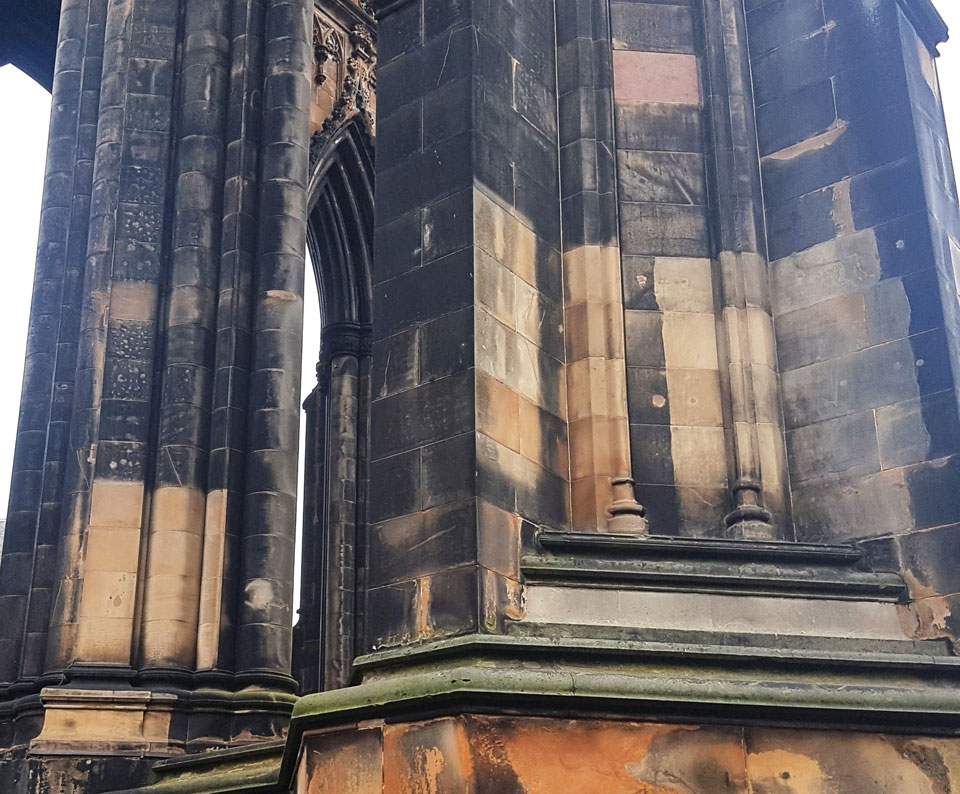

Scott’s Monument, west elevation. BGS © UKRI.

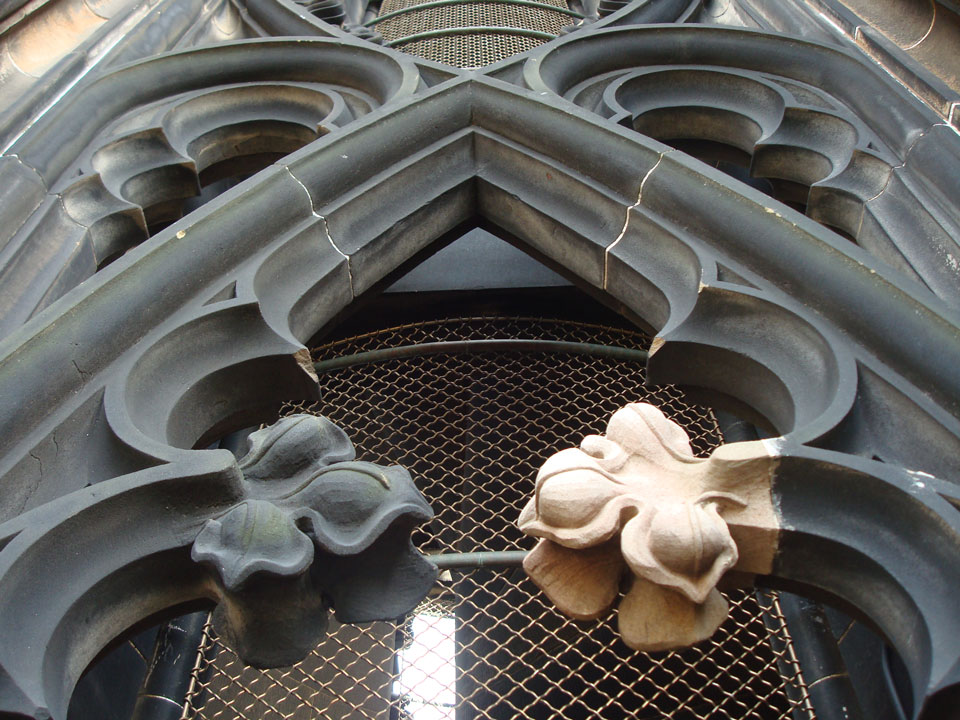

The ornate design required intensive stone carving: apart from the structure itself, there are sixty-four statues, primarily featuring characters from Scott’s novels. Unfortunately, it has been reported that as many as 23 of the 70 stonemasons died of silicosis during, or shortly after, the monument’s construction. In those days, the toll taken by quarrying and stone-building was intensive (another story well worth your time) and young men who began to work as stonemasons in their teens rarely lived to reach 35. In this respect, the monument can be viewed as a much of a homage to stone, architecture and the skill of the architect, quarriers, masons and craftsmen who created it, as to Walter Scott himself. It’s also a tribute to sound conservation decisions, which is where I would like to focus next in this spotlight.

The stone

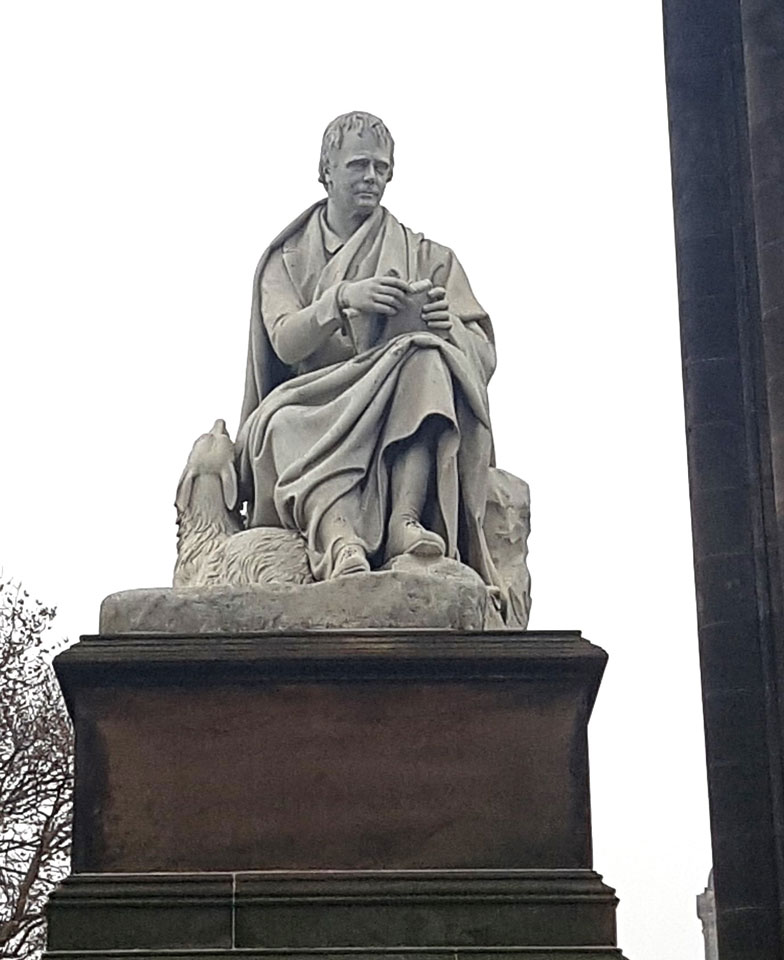

The pristine white stone for Scott’s statue was carved out of a single 30-ton block of marble by Sir John Steell, sculptor of many other statues around Edinburgh. The marble was sourced from the famous Carrara marble quarries in Italy, which also produced the marble Michelangelo carved. These quarries are still active and supplying the revered marble to this day.

Scott’s statue, with his dog Maida, carved of Carrara marble. BGS © UKRI.

There is a lot of information available for those interested to read more about Carrara marble, so I would instead like to focus on the sandstone used for the bulk of the monument. This stone was sourced locally from Binny Quarry, near Ecclesmachan in West Lothian, which also supplied lots of stone to many other buildings in Edinburgh, such as the National Gallery.

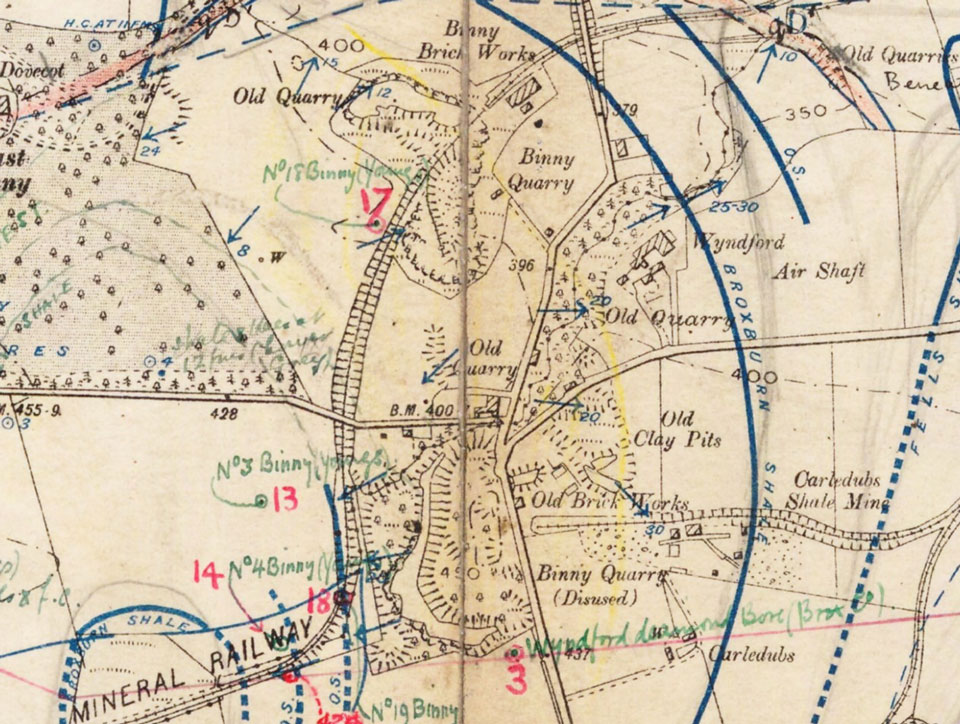

Extracts from a BGS field-slip (the document geologists fill with their observations while mapping the geology in the field, prior to creating geological maps), showing the quarry probably around 1915. Notice the development of the railway and the mentions to clay pits and brick works. The full package in one quarry and with easy transport all the way to Edinburgh! BGS © UKRI.

By 1855, the rock extracted at the quarry already had a strong reputation as a building stone due to its durability, the relative ease of work and its desirable appearance.

Historical samples of sandstone from Binny Quarry from the BGS Collection of Building Stones of Scotland. BGS © UKRI.

This building stone has been classified by BGS as Hopetoun Sandstone and we hold various historical samples in our BGS Building Stone Collections. The samples range in colour from very light grey to brownish-grey, and brown when freshly quarried. Weathered samples from buildings tend to appear browner, but the stone can be very brown even fresh, as the sample bottom-right in the image attests.

The sandstone is generally fine to medium-grained, with relatively large muscovite mica flakes visible, clearly indicating the bedding. The mica content is variable across the whole range of samples, yet ever present and characteristic.

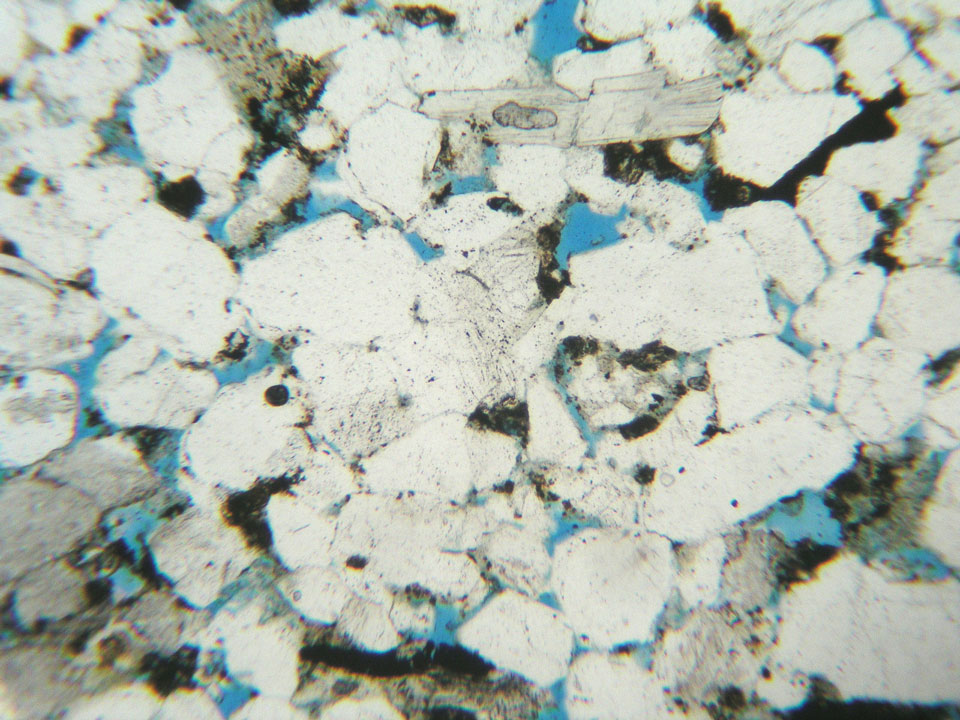

Under the microscope, it is a very quartz-rich sandstone (defined as a quartz-arenite), with a very small percentage of feldspar and rock fragments. Minor iron oxides/hydroxides exist. Relatively abundant mica flakes exist and are well aligned, indicating the bedding. Importantly, the grains are well cemented by a continuous coating of silica cement, making the stone rather durable. The total porosity is around 10 to 15 per cent, which is towards the medium to low end of Scottish Carboniferous sandstones. One of the stone’s most important characteristics (and a reasonably uncommon one, for a Scottish building stone), is its hydrocarbon content, which contributes to its brownish colour and other interesting properties, scattered as minute particles within its pore system.

Binny Quarry sandstone. The image was taken in plane-polarised light and the field of view is 1.3 mm wide. White grains are mostly quartz. Towards the top is a mica flake, with its characteristic tabular shape. The light-grey grains could be either rock fragments or feldspar grains. The larger black patches are iron oxides, but most of the tiny, smaller black particles are microscopic droplets of hydrocarbon. Porosity is highlighted by a blue dye resin. BGS © UKRI.

As the stone weathers, the brown colour intensifies as part of the hydrocarbons (and some of the iron content) mobilise and migrate to the surface of the stone. Allegedly, because of this hydrocarbon content, it seems that smog pollution (fly-ash particles product from coal combustion, dust, etc.) sticks easily (and faster) to this stone than in other sandstones used in Edinburgh at the time, blackening its surface. However, this could also be attributed to the monument’s location between the train station (old trains released a lot of smoke) and Princes Street.

One of my predecessors at BGS, Dr Tait, noticed in 1932 that ‘the replacement of water by small amounts of oil in the pores between grains contributed to the durability of the stone.’ These oils make the stone even less permeable than it may seem, due to their water-repellent qualities. In general, most of our fresh samples have a surprisingly lower permeability than you would initially expect by looking at comparable Scottish sandstone, or the sample’s thin section (10 to 15 per cent porosity). Not all samples have the same permeability though and, from a small sample of drop tests I conducted, it seems that the browner the sample, the more the water ‘beads up’ and does not penetrate through the porous system of the stone.

Conservation

Having admired the Sir Walter Scott Memorial for years, I have followed the evolution of the monument’s conservation efforts with interest.

Prior to the 1990s, sandstone from Clashach Quarry was used as a replacement building stone for the monument, a reasonably appropriate choice given the scarcity of quarries at the time. Between 1997 and 1999, a £1.4 million, multifaceted conservation plan was prepared and executed. It was decided that the monument’s current stones should be conserved, with the possibility of cleaning them. Photogrammetry was used to survey the monument and create detailed architectural drawings.

To clean, or not to clean … that is the question!

I am often asked why the monument was not cleaned, a question I myself had posed many years ago to a professor at the University of Edinburgh. He said that the question of cleaning or not cleaning the monument had been the source of much debate. Before making such a decision and, as it should be in any project involving stone cleaning, various test panels were carried out. The results of this test can still be seen on the south side of the monument today, with each panel cleaned using different methods and strengths of application. When you look at them, you can see how one of those methods removed the crust of pollution, but somehow managed to keep a thin patina, which in some ways respects the age of the monument. Other methods left the stone absolutely clean, still keeping the original brownish colour of the stone, whilst some methods appear to have altered the colour of the stone slightly to varying degrees.

The difference in outcomes across the test panels can be clearly seen in the images. The decision of what constitutes a ‘successful’ cleaning approach is partly a philosophical (and personal) one, as cleaner does not necessarily equate to better in terms of respecting the monument’s age and character. There is also an inherent risk of damaging the stone. It is reassuring, however, that twenty-five years after the cleaning tests, the test panels do not show any visual evidence of damage, which shows both the care with which this work was undertaken, as well as the durability of this particular stone. I would love to put my eyes, magnifying lens and nose close to those panels whilst holding information of which cleaning method was employed on each. There would be so much to learn!

One final reflection about these panels is that, a quarter of a century later, they do not appear to be much dirtier, which indicates how much cleaner the air we breathe is today compared to when the monument was built.

It is believed that the architect chose that particular stone because he knew that it would quickly turn black, and was therefore part of the monuments’ design, providing a more ‘gothic’ appearance and striking contrast with the white of the marble statue. As the stone was not suffering deterioration caused directly by the crust of soiling and pollution, the team of conservation architects, stone conservators and academics, in agreement with the heritage groups ultimately decided against cleaning the monument. They concluded that cleaning it would be disrespectful to the memory and intentions of the original architect and that cleaning it was ultimately not worth the risk of damaging the stone. I believe this was a wise ‘minimal intervention’ conservation decision.

Rocking the golf course

The conservation of the building has been carefully considered in other ways too. When it came to restoring damaged stone blocks, sculptures and other carvings, stone need to be sourced from the original quarry. By this time however, the site was in use as a golf course. The site was temporarily re-excavated for this project, with sufficient stone extracted and stored for future repairs (allegedly in the underground vaults of the monument) and the quarry was restored back to a golf course, which it remains to this day.

That wider vision about managing resources responsibly is what conservation should be about. Safeguarding sources of important stone, applying sound conservation practice and using locally sourced materials to minimise impact on the environment in addition to boosting local employment. It’s a win-win situation from every point of view.

Closing thoughts

Conservation of building stones is an ongoing process and, maybe one day in my old age, I will have a chance to get involved in further efforts aimed at the preservation of this iconic structure. Thanks to the excellent sourcing of the stone, the skill of the original craftsmen and the valuable conservation efforts that have come before, the Scott Monument is in good health. I hope that this continues well beyond my lifetime.

Further information

About the author

Luis Albornoz-Parra

Building stones geologist and enquiries officer

Relative topics

Latest blogs

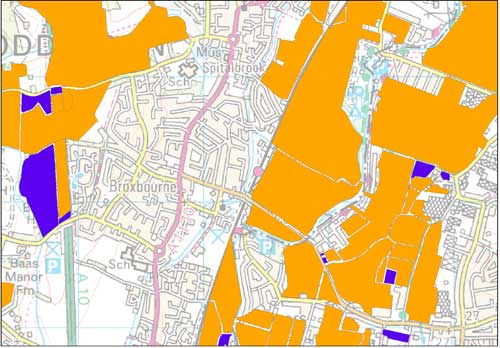

Historical planning permission database

This dataset contains hand-drawn boundaries showing mineral related planning permissions and land use collated from the 1940s to the mid 1980s.

Pioneering tool expanding to analyse agricultural pollution and support water-quality interventions

06/02/2025

An online tool that shows which roads are most likely to cause river pollution is being expanded to incorporate methods to assess pollution from agricultural areas.

How can Scotland re-establish its building stone industry?

14/11/2024

British Geological Survey research, commissioned by Historic Environment Scotland, reveals an opportunity to re-establish the Scottish building stone market in order to maintain the country’s historic buildings.

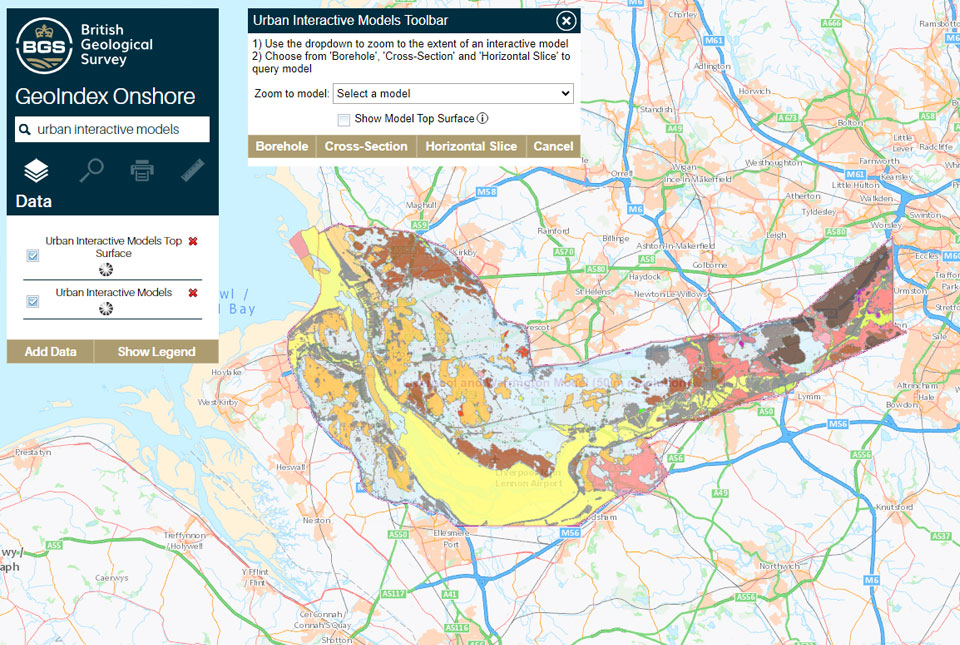

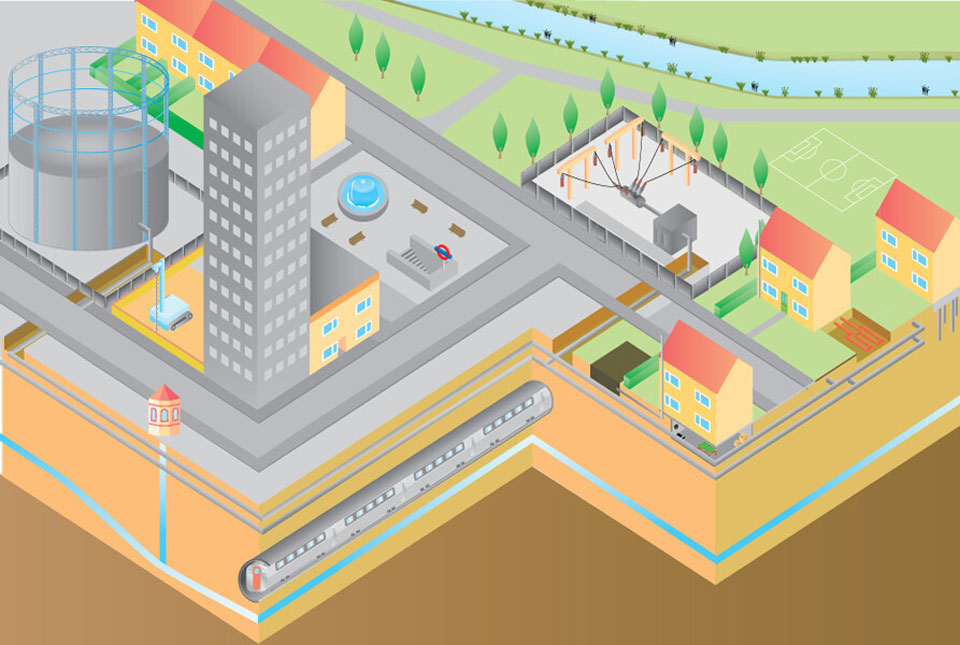

What lies beneath Liverpool?

11/10/2024

The geological secrets lying under the surface of Liverpool and Warrington have been unveiled for the first time in BGS’s 3D interactive tool.

UKGravelBarriers

Increasing our understanding and modeling capabilities of gravel beach and barrier dynamics.

New community launched to support effective management of the subsurface

03/10/2024

The initiative aims to increase knowledge exchange on subsurface issues between interested parties involved in subsurface policy and planning.

Monitoring coastal change from space

BGS is helping to develop applications that detect and track coastal erosion and accretion from space to inform coastal management plans.

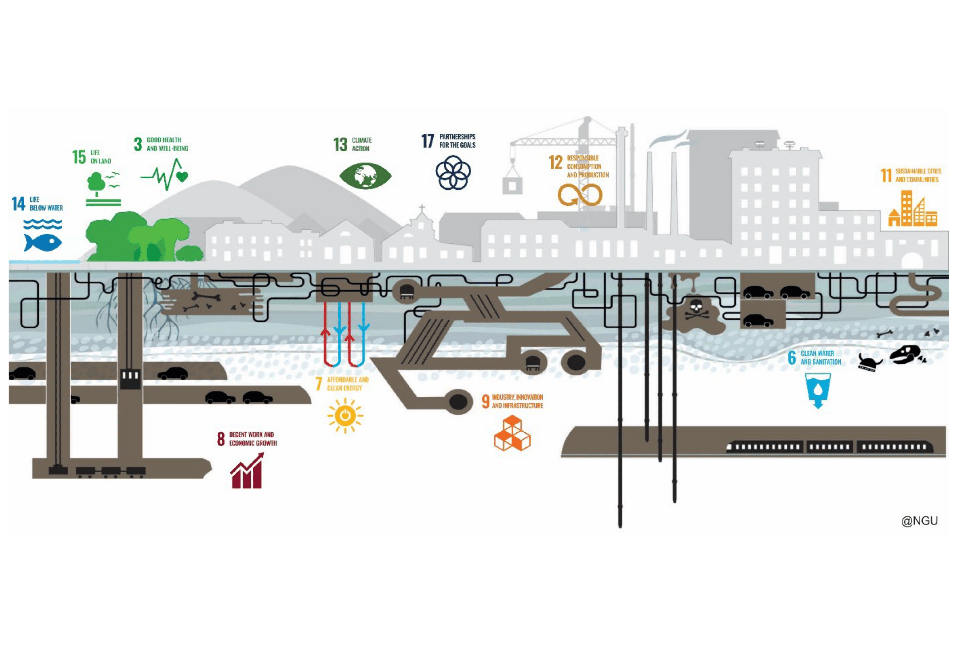

Delivering a sustainable urban future for Europe through geoscience

08/05/2024

Research, led by BGS and EuroGeoSurveys’ Urban Geology Expert Group, explores how urban geoscience is reflected in European urban and environmental policy.

Building stones spotlight: the Sir Walter Scott Memorial 25 years after its conservation

29/04/2024

BGS geologist, Luis Albornoz-Parra, discusses the iconic Edinburgh monument, the building stones used in its construction and the result (so far) of its conservation efforts.

The Common Ground project

The Common Ground project aims to enhance the value of GI data for the UK construction and environmental sectors.