Hungry like a wolf: new insights from old bones housed in the BGS museum collections

BGS scientists are studying the diets of ancient British wolves and how they adapted to changing environments.

18/01/2024

Studying the diet of an animal that roams the Earth today is relatively straightforward. Their eating habits can be easily tracked and their food sources monitored using their faecal matter (‘scat’). But how do you study the diet of animals that have been dead for thousands of years? The NERC/UKRI-funded project ‘Hungry like a wolf’, carried out by BGS together with Royal Holloway University London, aims to do exactly that: study the diets of wolves that lived in Britain during the last 250 000 years.

Investigating ancient animals’ diets

The project adopts the adage ‘we are what we eat’. The type of diets an animal consumes are imprinted on the wear and tear on their teeth and the stable isotope signature in their body tissues. For animals that are no longer alive, studying these signatures in fossil bones and teeth provides a window into the animal’s diet and consequently into how their diets have changed over time with fluctuating climatic and ecological conditions. The project aims to understand how wolves have adapted to changing environments by comparing the diet of past (10 000 to 250 000 years) and present wolves, along with other predators and prey from different locations across Europe.

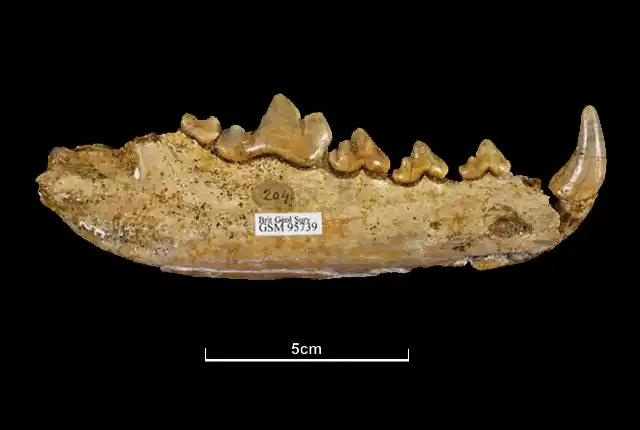

Examples of subfossil bone material selected from the BGS collections for subsampling. BGS © UKRI.

Top ice age predators

Although they were the first animals to be domesticated by humans, wolves were well-established members of the Pleistocene (ice age) carnivore community in Europe. As one of the top predators, wolves keep the populations of their prey in check and, as a knock-on effect, affect the biodiversity of other predators in the area as well as other animal and plant species further down the food chain by limiting over-predation and over-browsing on vegetation. Wolves are therefore considered the most influential large predator in the northern Eurasia region.

Project aims

Unfortunately, many surviving populations of these charismatic animals are today endangered because of human persecution and environmental change. Serious concerns exist as to the viability of European wolf populations under different scenarios of environmental and climate change. It is therefore essential to understand how wolves have adapted to changing circumstances in the past, so that current and future conservation policy can be appropriately tailored.

The project is being carried out by Dr Angela Lamb and Dr Diksha Bista at BGS, together with Prof Danielle Schreve, Dr Fabienne Pigière and Dr Amanda Burtt (Royal Holloway University London). It will involve museum collections from across the UK.

The collections housed here at BGS were some of the first to be analysed. These collections comprise Quaternary (up to 2.58 million years ago) subfossil bone material that has been held in the museum since the late 1800s. Specimens were collected from Ilford by Richard Payne Cotton and donated in 1877, whilst those from Crayford are from the collection of Frederick Spurrell, donated in 1894.

Although the material was collected over 150 years ago, advancing research technologies allow us to uncover new information that can enhance our understanding of past environments and ecosystems. Even though the subsampling involves removing a small amount of material from the selected bones, the insights gained from the analysis can add significantly to the understanding of the fossils held in the collection since the Victorian era.

Louise Neep, BGS Museum Curator.

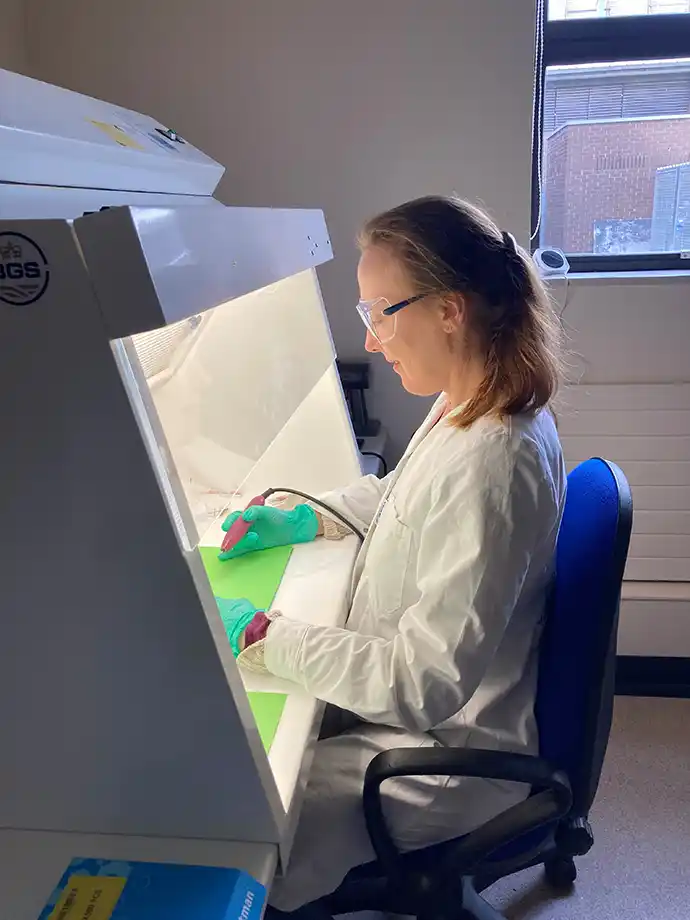

Laboratory analysis

In the laboratory, collagen will be extracted from the bones and analysed for nitrogen (N), carbon (C) and sulfur (S) isotopes. Recent technical developments within the Stable Isotope Facility now allow the measurement of these isotopes on a significantly smaller amount of collagen (10 times smaller). This advance means much less sample needs to be removed from the fossils, thus preserving the integrity of precious museum specimens.

Dr Fabienne Pigière sampling the fossil material. BGS © UKRI.

Acknowledgements

We’d like to thank Paul Shepherd (collections manager) and Simon Harris (conservator) for their support with the project.

About the authors

Dr Angela Lamb

Research scientist

Louise Neep

Curating technician

Relative topics

Latest news

Funding awarded to UK/Canadian critical mineral research projects

08/07/2025

BGS is part of a groundbreaking science partnership aiming to improve critical minerals mining and supply chains.

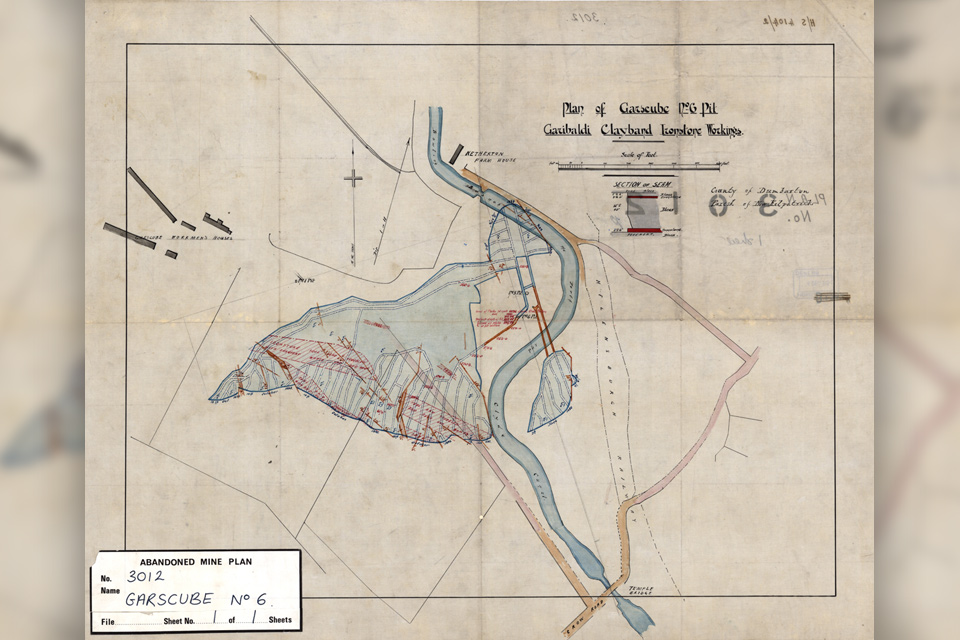

Release of over 500 Scottish abandoned-mine plans

24/06/2025

The historical plans cover non-coal mines that were abandoned pre-1980 and are available through BGS’s plans viewer.

New collaboration aims to improve availability of real-time hazard impact data

19/06/2025

BGS has signed a memorandum of understanding with FloodTags to collaborate on the use of large language models to improve real-time monitoring of geological hazards and their impacts.

Modern pesticides found in UK rivers could pose risk to aquatic life

17/06/2025

New research shows that modern pesticides used in agriculture and veterinary medicines have been found for the first time in English rivers.

Goldilocks zones: ‘geological super regions’ set to drive annual £40 billion investment in jobs and economic growth

10/06/2025

Eight UK regions identified as ‘just right’ in terms of geological conditions to drive the country’s net zero energy ambitions.

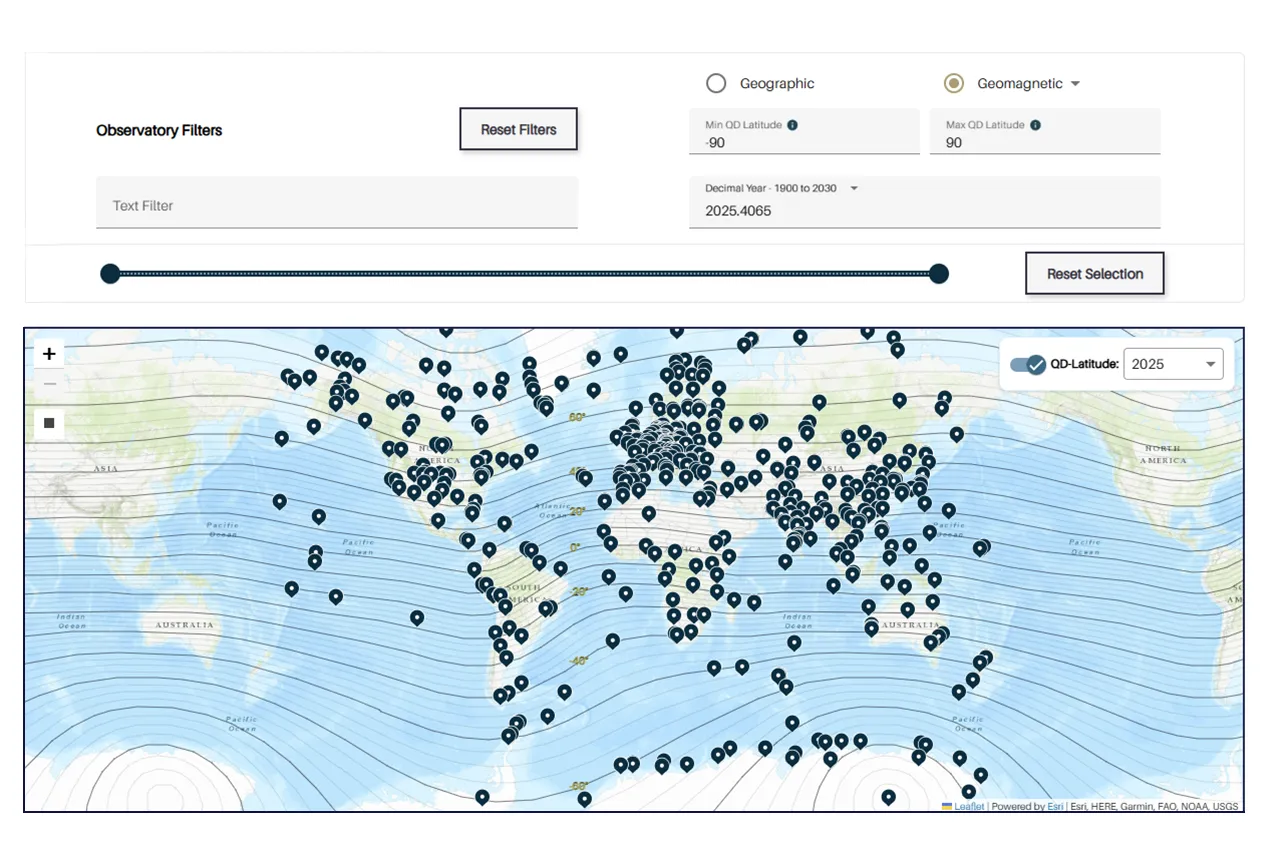

Upgraded web portal improves access to geomagnetism data

02/06/2025

BGS’s geomagnetism portal, which holds data for over 570 observatories across the world, has received a significant update.

BGS digital geology maps: we want your feedback

29/05/2025

BGS is asking for user feedback on its digital geological map datasets to improve data content and delivery.

What is the impact of drought on temperate soils?

22/05/2025

A new BGS review pulls together key information on the impact of drought on temperate soils and the further research needed to fully understand it.

UK Minerals Yearbook 2024 released

21/05/2025

The annual publication provides essential information about the production, consumption and trade of UK minerals up to 2024.

BGS scientists join international expedition off the coast of New England

20/05/2025

Latest IODP research project investigates freshened water under the ocean floor.

New interactive map viewer reveals growing capacity and rare earth element content of UK wind farms

16/05/2025

BGS’s new tool highlights the development of wind energy installations over time, along with their magnet and rare earth content.

UKRI announce new Chair of the BGS Board

01/05/2025

Prof Paul Monks CB will step into the role later this year.