Geology and cycling: the rocks behind the race

The UK’s biggest and most prestigious bike race would not be what it is today, without a nod to the humble rock.

08/09/2022 By BGS Press

The adrenalin, the attacks, the climbs, sprints, chases and, for some, the incredible victories, would arguably not be such a spectacle were it not for Britain’s incredibly diverse geology.

Though the link is rarely made, the geology beneath our feet is ultimately responsible for shaping our landscape today, even shaping our Strava segments.

Our rich variety of landscapes, largely consisting of Triassic, Jurassic, Cretaceous and Tertiary strata, has paved the way to victory for the world’s greatest cyclists across mountains, countryside and coastline for decades.

This year’s edition in 2022 is set to be no different, with eight days of racing from the iconic ‘granite city’ of Aberdeen in Scotland to the distinctive chalk stacks of the Needles on the Isle of Wight.

But why are some stages of this year’s Tour hillier than others? It’s ultimately determined by the rocks and sediments of an area and the subsequent geological processes that have been eroding, folding or faulting them over the hundreds of millions of years since they were deposited.

Here we take a closer look at some of the rocks behind the race.

Sunday 4 September

North-east Scotland boasts a spectacular and unique landscape, formed over millions of years by both geological and geomorphological processes.

The geological story of this region, with its panoramic vistas, is possibly too big to tell here. Perhaps the most iconic is at this year’s start line, in Aberdeen. The city owes its distinctive appearance to the local grey granite, which many of its buildings are made from. It includes the famous ‘Granite Mile’ down Union Street, which earned it the title ‘Granite City’. The world-famous Aberdeen granite is made up of typical granite minerals, including plagioclase, alkali feldspars (orthoclase and microcline), quartz, biotite and muscovite.

The expansion of commerce and industry in the 18th century increased demand for granite. Many magnificent buildings, such as the Marischal College, the largest granite building in Europe, were built at the height of the industry. The balusters on the old Waterloo Bridge in London came from Aberdeen in the 1800s.

The Aberdeen granite was emplaced into rocks of the Dalradian Supergroup during the Caledonian Orogeny, which represents the closure of the ancient Iapetus Ocean that separated Avalonia and Laurentia. The collision started in the Silurian and continued into the Ordovician over a time scale of 30 million years, bringing the UK together for the first time.

As the riders go north from Aberdeen they will encounter dramatic valleys (and category two and three climbs!) that were carved out by glaciers to expose the oldest rock on this year’s tour. As the riders head back south towards the towering Cairngorms, they face the first-ever opening day summit finish in modern cycling race history. The Old Military Road climb from Auchallater to Glenshee Ski Centre, at the head of the Cairnwell Pass, which was formed by glaciers and is now one of the country’s highest and most scenic roads. The climb measures 9.1 km, with the final five kilometres averaging a gradient of 4.8 per cent.

Thursday 8 September

We’re preparing to see some of the world’s top riders pass through Nottinghamshire on stage five, which takes place between West Bridgford and Mansfield and loops through Keyworth, home to BGS headquarters.

A comparatively flat and rolling stage, the geology of this mainly northerly route though Nottinghamshire towards Retford, passes over rocks originally deposited some 250 to 200 million years ago during the Triassic, mostly made up of the Sherwood Sandstone Group, a yellowish sandstone (best seen at Castle Rock in Nottingham), and the slightly younger Mercia Mudstone Group. Since both sandstone and mudstone are considered to be fairly weak rocks, the landscape here features only mild elevations, but we hope this will allow the riders plenty of opportunity for some early attacks and breakaways.

The flatter landscape developed as the Sherwood Sandstone has been eroded and flattened by the River Trent in the recent past. Over time the river’s location has shifted, carving a flat, narrow plain that extends south of Nottingham for much of the first portion of the route from West Bridgford.

As the riders travel further north through villages like East Leake, Keyworth and onto Southwell, the Sherwood Sandstone becomes weaker. The surface is more like a loose sand, meaning the landscape is less likely to form any particularly knotty climbs. Despite this, it is fascinating to know that this is partially a result of the last ice age, as glaciers damaged and weakened the rock. The riders can expect to encounter a series of mound-like hills and ramps, which they might use strategically to advantage.

It is the latter part of the race towards Mansfield, over Carboniferous rocks, that will be most challenging. Here, the underlying geology is made up of different rock types from mudstones, siltstones, coal, sandstones, gritstone and limestones. The latter three examples are much stronger than sandstone and good at forming hills and the kind of elevations we’ll see in the later stage of the race. Here, the riders will encounter a landscape formed by rocks deposited roughly 360 to 300 million years ago.

Carboniferous rocks have greatly influenced the UK’s development; they are the rocks from which we mined vast quantities of coal that powered the Industrial Revolution. Both Sheffield and Nottingham’s intimate history with mining is a direct result of geology beneath its surface and it’s very likely to influence the winner of Stage 5 !

Saturday 10 September

Dorset promises to be a picturesque and challenging 109-mile stage that begins on the Esplanade and passes the famous golden cliffs of West Bay. Dorset is home to the Jurassic Coast – England’s only Natural World Heritage Site. Riders will travel parallel with the West Dorset Heritage Coast before passing through Dorchester, West Lulworth and Corfe Castle.

Riders will battle for three Škoda King of the Mountains climbs, all falling within the Dorset Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The first, at Daggers Gate above West Lulworth, is close to the world-famous limestone arch in the Portland Stone Formation at Durdle Door. The Portland Stone is 33 m thick here, which is its thickest, but the arch top itself is just 5 m thick. From the beach, spectators can get a good view of the near-vertically dipping limestone beds.

Close to the village of West Lulworth is the beautiful Lulworth Cove, formed when a weakness such as a fault or a crack within the Portland Stone Formation at the mouth of the cove was exploited by sea water. This allowed water to pass through and erode the softer rocks further inland. The result displays a beautiful array of sandstones, mudstones and limestones, all of which formed during the Cretaceous Period. The oldest rocks are at the mouth of the cove and consist of limestones of the Portland Stone Formation.

Other climbs on stage 7 include Whiteway Hill, which sits on a ridge, and Okeford Hill, with 55 km of racing to go. All the strata here form a part of the Purbeck Monocline, which reaches all the way to Isle of Wight.

The iconic Corfe Castle is built upon a steep-sided Chalk ridge in the Purbeck Hills, which features a distinctive gap. Around a million years ago, two parallel water courses exploited weak points in the underlying geology and eroded gaps in the ridge, isolating the hill on which the castle sits.

Sunday 11 September

Rich in geodiversity, the Isle of Wight will undoubtedly welcome an exciting finale with its stunning coastline and rolling hills. Starting in Ryde and culminating at the Needles, the race will take riders across the entire island and, wherever you are on the Isle, you won’t be far from the action.

The Isle boasts a stunning array of habitats for flora and fauna all influenced by the underlying geology. The distinct shape and topography of the island is controlled by the dominant east-to-west trending Chalk downlands. This elevated ridge creates a spine across the island and is formed by intensely hardened, folded and faulted chalk rocks, presenting numerous challenges for the riders like the 11.4 km Bradling Down (7.3% per cent on average), the day’s first Škoda King of the Mountains climb, a mere 10 miles from the start.

By contrast, central parts of the island through Newport and Blackwater are characterised by the Lower Cretaceous wolds. Landscapes of this domain are defined by low-lying, gently undulating topography dominated by arable farmland and pasture.

It’s the island’s interior and southern tip that are likely to feature plenty of racing action, dominated by the features typical of Chalk downlands: high rolling hills, steep southern scarp slopes and deeply incised valleys, with climbs like the 1.5 km Cowleaze Hill (6.2 per cent average).

The oldest rocks (the Wealden Group, about 140 to 125 million years old) on the island are seen where the Cretaceous wolds meet the sea at Brighstone Bay on the south coast and at Sandown in the east. The muds exposed at beach level can often reveal fossils.

The well-known three chalk stacks of the Needles, on the western side of the island, are composed of near-vertically bedded Chalk. Rare and historic shipwrecks, dating back to the 16th and 17th centuries have occurred just below along the Shingles Bank, a shoal of pebbles beneath the waves and a well-known navigational hazard for ships entering the Solent from the west.

This year’s race culminates with a 1.5 km climb up Tennyson Down, the final 400 m at a gradient of 9.6 per cent making it the toughest finish of a Tour of Britain stage in modern history.

The materials that make a bike

It’s not only our landscapes that are influenced by geological processes; our equipment is too. Since lightweight carbon fibre began to dominate the performance cycling world nearly two decades ago, races like the Tour of Britain have featured even lighter, stiffer and more impressive bikes and designs.

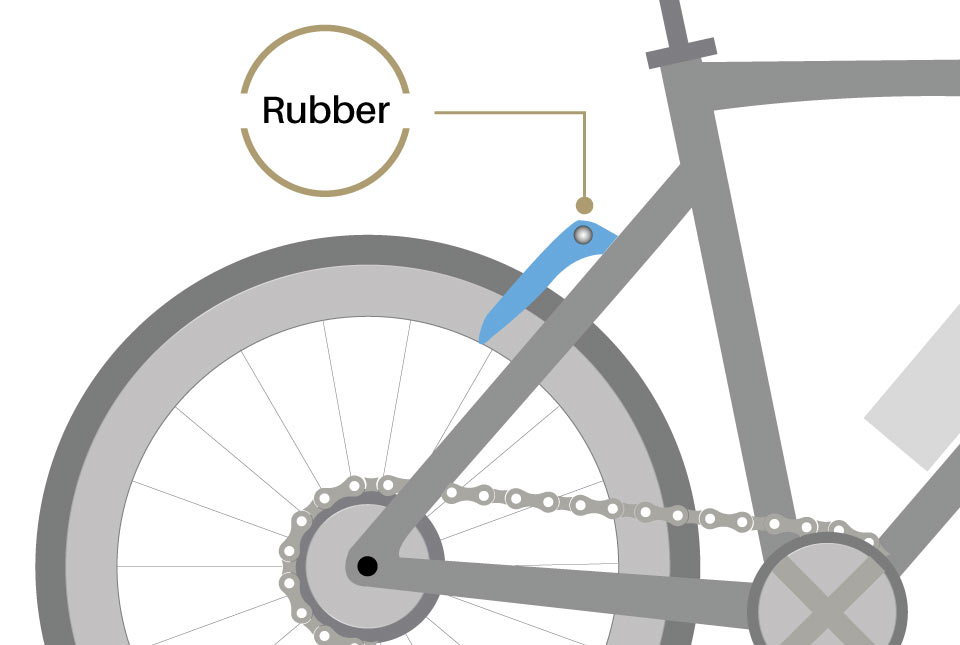

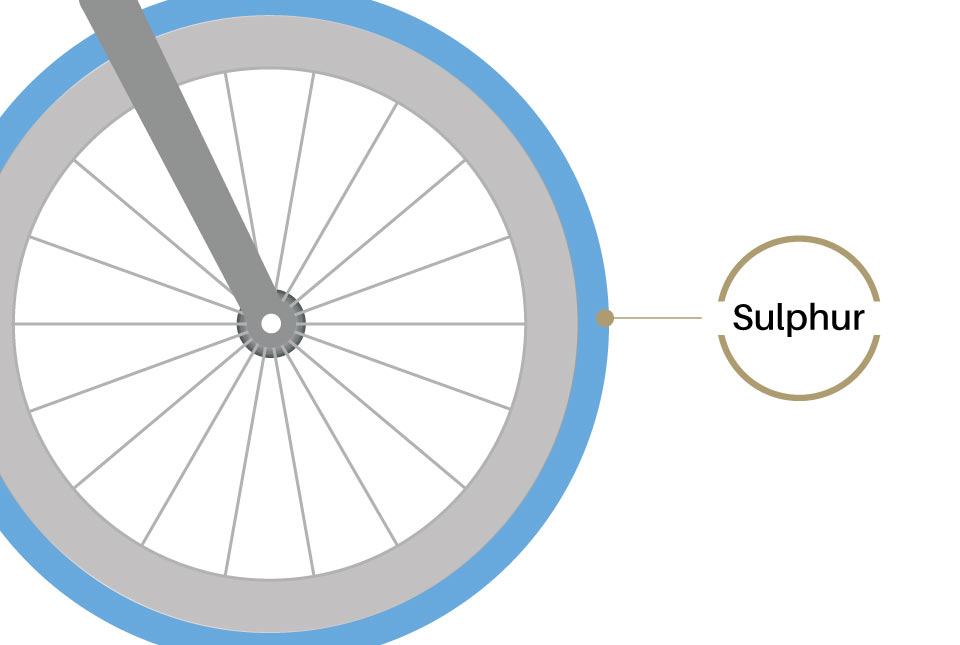

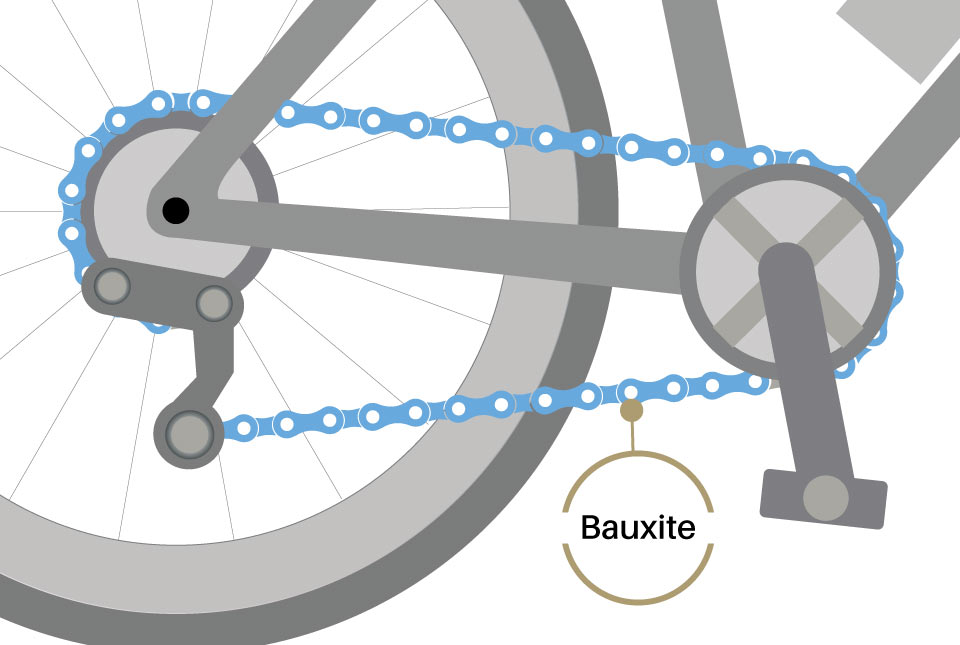

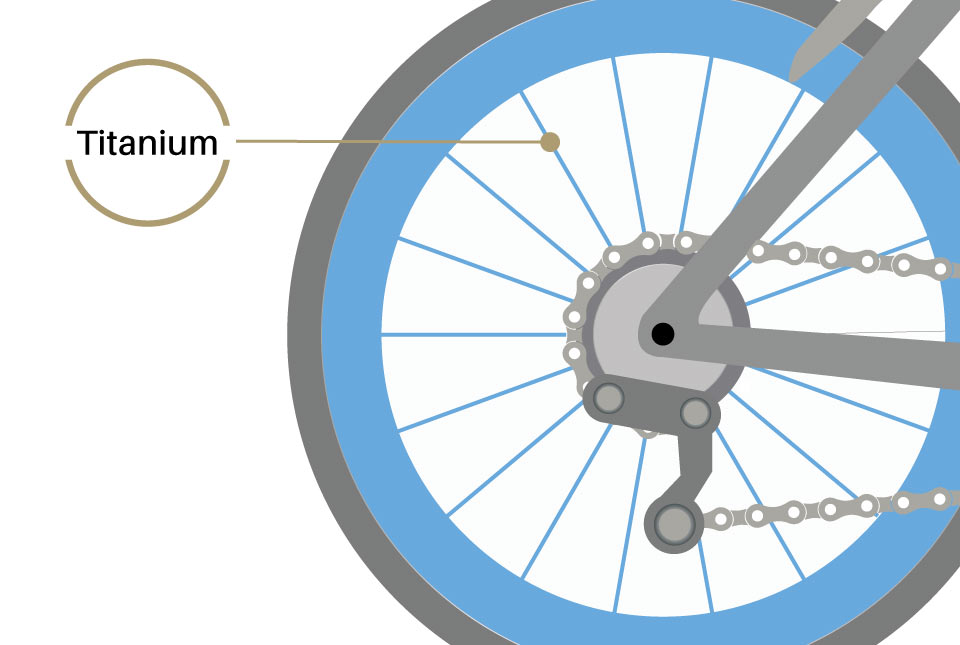

Many of the components found on a racing bike require materials derived from the ground beneath our feet. In case you’re wondering, here are the basic materials required and some are more obscure than you might think:

The chainset needs to be durable and is made from aluminium, which is produced from the rock bauxite. Australia is the largest global producer of bauxite (39 per cent). It’s probable that any aluminium in your bike is a mix of recycled and new material. BGS © UKRI

Spokes are made from strong, light, titanium, which comes from minerals such as rutile and ilmenite. Canada and China are the largest producers, with 16 per cent and 33 per cent respectively. BGS © UKRI

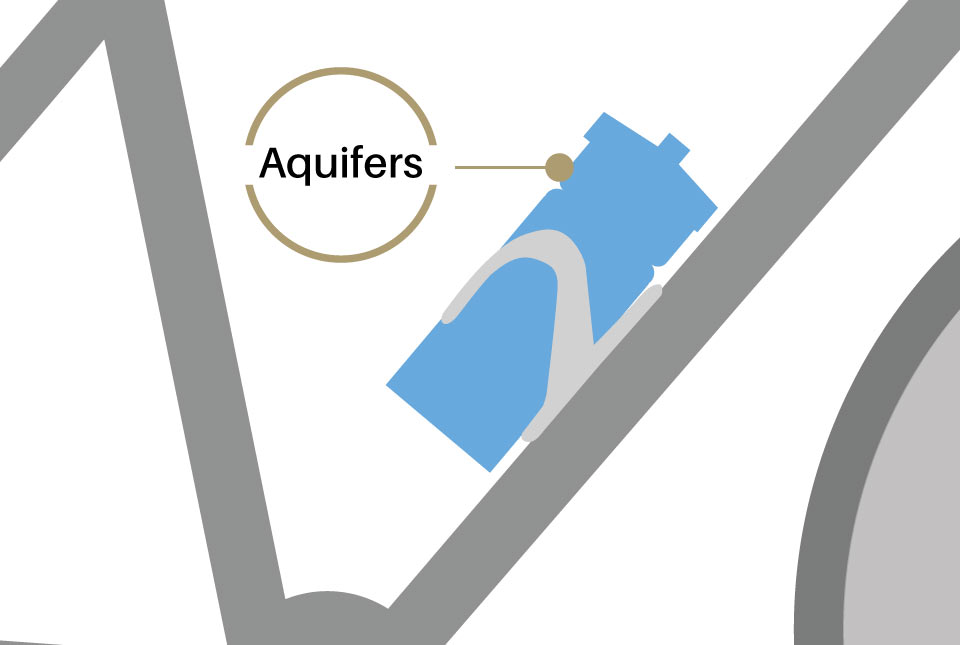

A third of our drinking water in the UK comes from underground aquifers such as the Sherwood Sandstone. BGS © UKRI

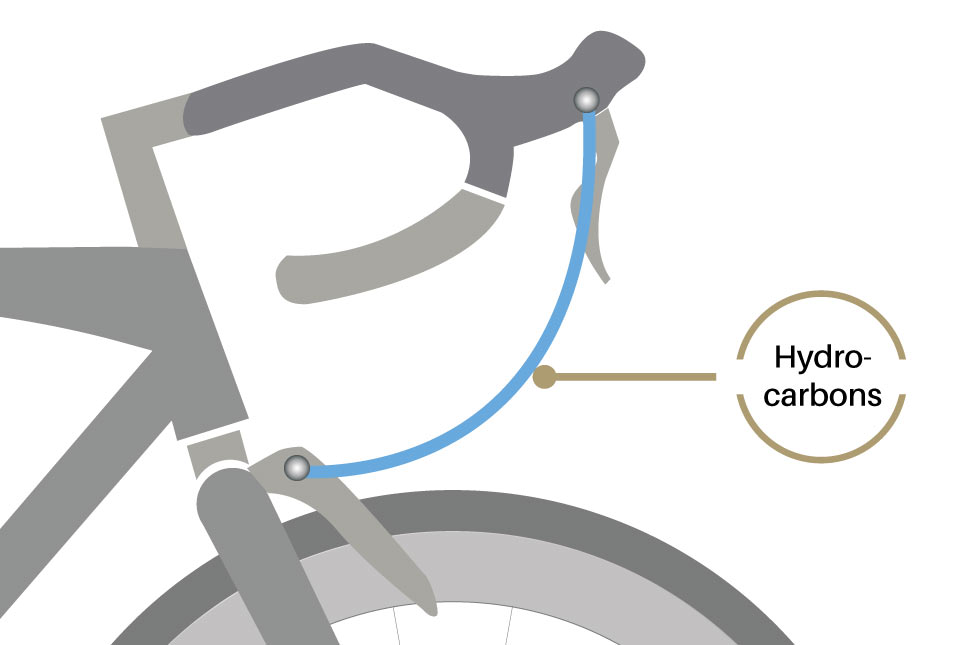

Brake levers are made of plastic, which is made from crude oil. The USA, Saudi Arabia and Russia produce 43 per cent of the world’s oil. BGS © UKRI

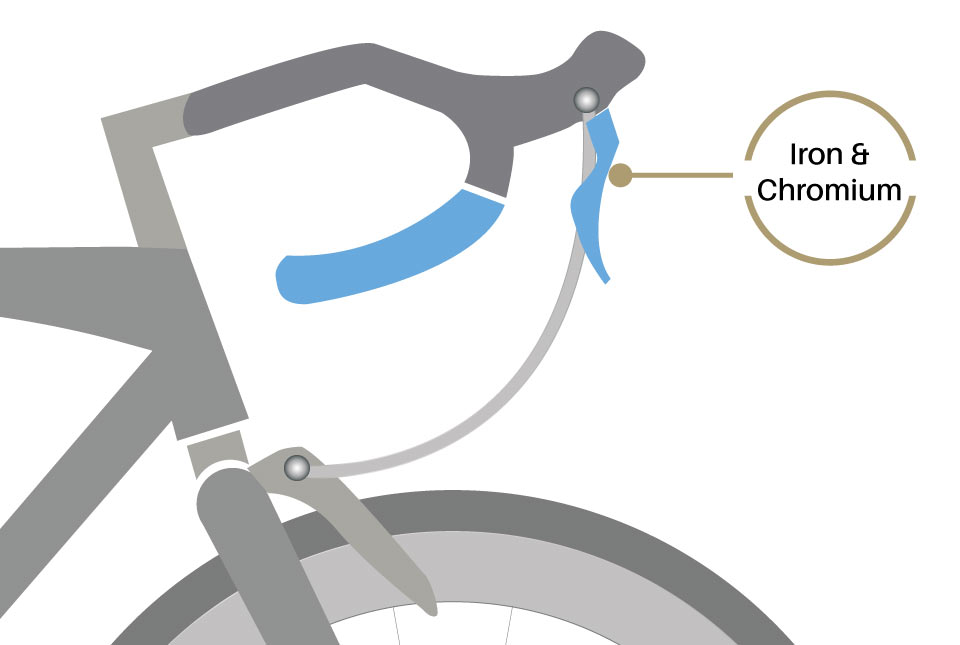

The steel cables need to be strong and are made from iron and chromium. Australia mines around 30 per cent of the world’s iron ore and South Africa is the biggest producer of chromium minerals. BGS © UKRI

So if, like us, you’re thinking about exploring Britain’s fascinating geological wonders on a bike, why not take a moment to appreciate the world beneath your wheels and the geological conditions that influence your next cycling adventure.

Relative topics

Latest blogs

AI and Earth observation: BGS visits the European Space Agency

02/07/2025

The newest artificial intelligence for earth science: how ESA and NASA are using AI to understand our planet.

Geology sans frontières

24/04/2025

Geology doesn’t stop at international borders, so BGS is working with neighbouring geological surveys and research institutes to solve common problems with the geology they share.

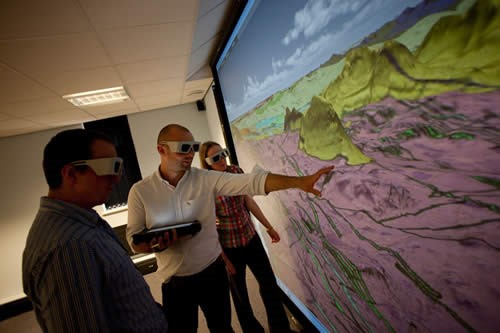

Celebrating 20 years of virtual reality innovation at BGS

08/04/2025

Twenty years after its installation, BGS Visualisation Systems lead Bruce Napier reflects on our cutting-edge virtual reality suite and looks forward to new possibilities.

Exploring Scotland’s hidden energy potential with geology and geophysics: fieldwork in the Cairngorms

31/03/2025

BUFI student Innes Campbell discusses his research on Scotland’s radiothermal granites and how a fieldtrip with BGS helped further explore the subject.

Could underground disposal of carbon dioxide help to reduce India’s emissions?

28/01/2025

BGS geologists have partnered with research institutes in India to explore the potential for carbon capture and storage, with an emphasis on storage.

Carbon and oxygen isotope analysis of carbonates and the development of new reference materials

18/12/2024

Dr Charlotte Hipkiss and Kotryna Savickaite explore the importance of standard analysis when testing carbon and oxygen samples.

Studying oxygen isotopes in sediments from Rutland Water Nature Reserve

20/11/2024

Chris Bengt visited Rutland Water as part of a project to determine human impact and environmental change in lake sediments.

Celebrating 25 years of technical excellence at the BGS Inorganic Geochemistry Facility

08/11/2024

The ISO/IEC 17025 accreditation is evidence of technical excellence and reliability, and a mark of quality assurance.

Electromagnetic geophysics in Japan: a conference experience

23/10/2024

Juliane Huebert took in the fascinating sights of Beppu, Japan, while at a geophysics conference that uses electromagnetic fields to look deep into the Earth and beyond.

Exploring the role of stable isotope geochemistry in nuclear forensics

09/10/2024

Paulina Baranowska introduces her PhD research investigating the use of oxygen isotopes as a nuclear forensic signature.

BGS collaborates with Icelandic colleagues to assess windfarm suitability

03/10/2024

Iceland’s offshore geology, geomorphology and climate present all the elements required for renewable energy resources.

Mining sand sustainably in The Gambia

17/09/2024

BGS geologists Tom Bide and Clive Mitchell travelled to The Gambia as part of our ongoing work aiming to reduce the impact of sand mining.