Probably one of the most iconic sites in the city, Nottingham Castle is well known worldwide as the mythical centre of the fight between Robin Hood and the Sherriff of Nottingham. Despite this acclaim, the very foundation that the castle sits upon is often overlooked, by which I of course mean the rocky cliff of ‘Castle Rock’. Castle Rock is made of the same sedimentary rock that is located directly beneath most of the city; indeed it is this rock — part of a group called the Sherwood Sandstone Group — that hosts the myriad of tunnels and caves for which the city is also known.

This sandstone records a period of history that would have looked very different from our modern understanding of Nottingham. This is because the sandstone was originally deposited by a huge river that flowed all the way from northern France some 250 million years ago during a geological period called the Triassic. This river would have been very wide, likely thousands of metres, and it flowed over a barren, hot, desert-like landscape.

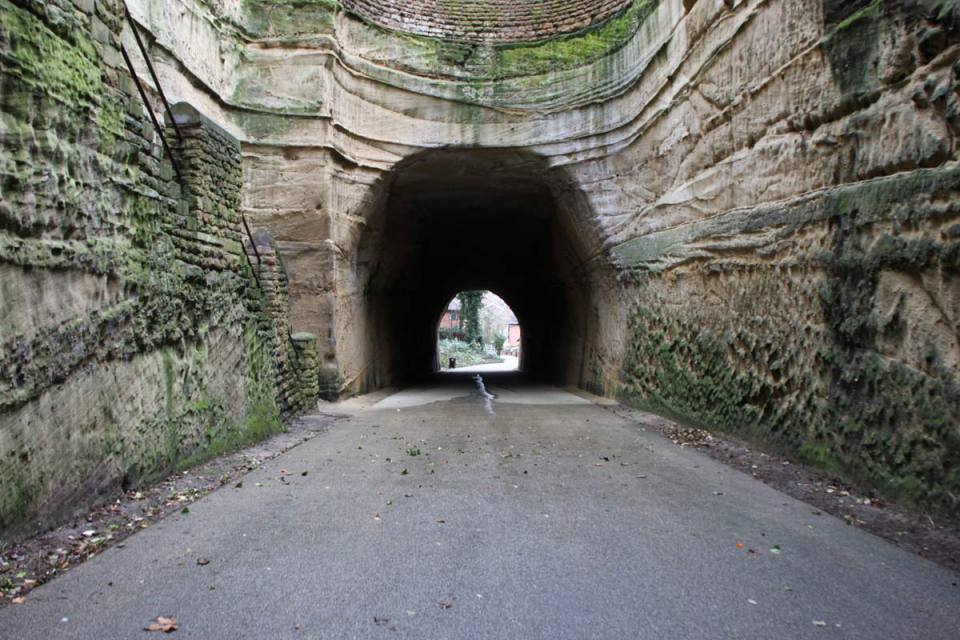

The bottom entrance to Park Tunnel. The pristine walls allow a real insight into the structure of the sandstone. Note how the sloping, line-like structures (cross-bedding) in the sandstone appear to change as they pass from one wall into another. BGS © UKRI.

Structures in the rock

The evidence of this ancient river is recorded in the rocks we now see in places like Castle Rock. Looking upon the approximately 30 m-high cliff you see yellowish rock. But look closer and you’ll find all manner of subtle colour changes, from pale yellows to deep reds and oranges, and strange curved layers.

Cross-bedding

These layers are interesting as they run contrary to the general thinking that sedimentary rocks are made of horizontal layers (like those you’d get in a good cake!) but if you spend even a couple of minutes looking at Castle Rock itself, it’s relatively difficult to see any horizontal layers in the cliff at all.

These layers are all curved: some look like interlocking U shapes while others exhibit more subtle curved lines, but they are all actually the same thing: examples of huge fossilised ripples that were flowing within the channel of the ancient river. The technical name for these curved layers is ‘cross-bedding’. Some of you will be familiar with seeing sandbars or small ripples in rivers; these are the same but much bigger!

If you look at satellite images (Google Earth is great for this!) of any of the big rivers in Bangladesh for example, you can see sand bars in almost every river channel and it’s very likely that our ancient Nottingham river looked very much like these. The difference in some of the sizes of these curved layers relates to the size of the original sandbar.

Pebbles

Alongside the crossbedding there are lots of pebbles scattered throughout the cliff. Some are small (coin sized) while others can be much larger (‘potato-sized’, as a guest on a geological tour once told me). Some of these pebbles can be made of milky-white quartz, some are dark, almost black igneous pebbles, some are chocolate-brown mudstone pebbles. The mudstone pebbles can in places be grey-green; this is not their original colour but a colour change caused by water present in the ground.

The mudstone pebbles are actually very soft and are often smeared into weird shapes. A quick trip into the famous Ye Olde Trip to Jerusalem pub and these pebbles can be seen with ease. You’ll see that other pebbles often stand out from the sandstone walls and cliffs but that the mudstone pebbles are often recessed, which is down to the mudstone being relatively soft and easily eroded.

It’s well worth a visit to Castle Rock and spotting all the beautiful, curved layers in the cliff is a good way to spend time on a sunny day, especially given ample provisions for sustenance on the doorstep.

Park Tunnel

One of the hidden gems in all the sandstone outcrops in and around Nottingham must be Park Tunnel; a tunnel originally made for horse-drawn carriages that was allegedly too steep to safely use. But despite the reason for it being dug, it is without doubt the most pristine sandstone outcrop in all the city. You can see all manner of wonderful features in the walls and ceiling of the tunnel.

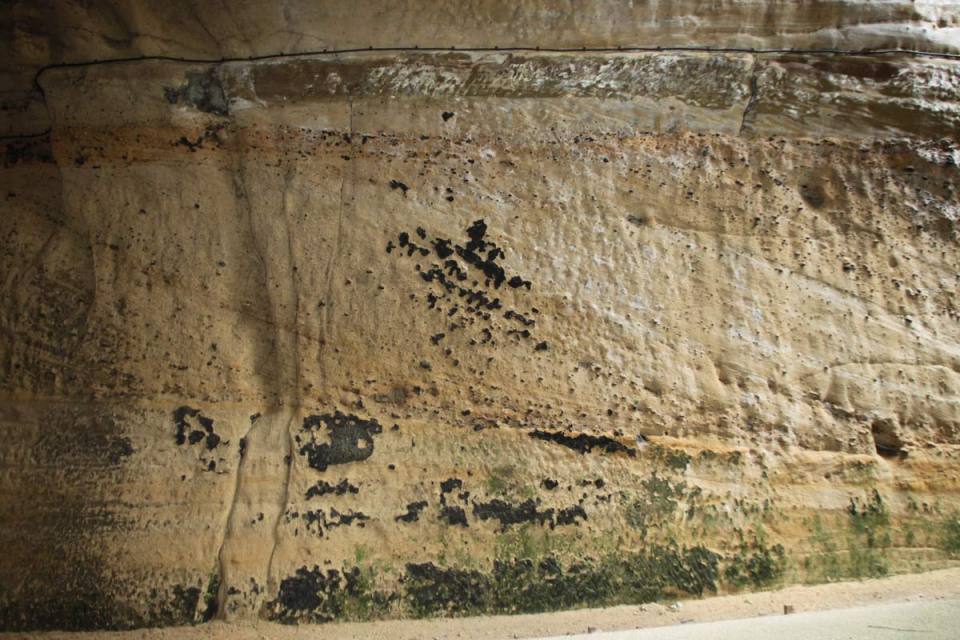

Cross-bedding can create really intricate and wonderful patterns in rock. Here, the rock itself varies in colour, from yellow to brick-red to grey white. The original colour of the sandstone was most likely yellow. The brick-red colour often occurs following some of the layers in the rock, and was caused a long time ago by chemical changes after deposition. The grey-white colour seen in the central parts of the tunnel is due to modern weathering and staining, most likely from water. BGS © UKRI.

If you can spend a few minutes it is worth look at the walls in the entrance of the tunnel itself, on the downslope side. The layers in the sandstone are almost all curved and you’ll notice that they all appear to be curving in the same direction, although the keen-eyed amongst you might find small isolated lenses of sandstone where the curves are going in the opposite direction. All these layers were formed from sandbars and ripples in the large river discussed above.

Toward the top end of the tunnel you can see the complexity of the crossbedding in the curved surfaces above the tunnel entrance. You can fully follow the features from one side of the tunnel walls to the other. BGS © UKRI.

Further in from the entrance to the tunnel you can see more curved layers in the wall that cross-cut and meet each other in intricate patterns. You might even spot the big U-shaped layers I mentioned earlier that cut deeply into underlying ones, thickening considerably as they do so.

Good examples of crossbedding can be seen in the tunnel itself. Crossbedding is the technical name given to these line-like features seen throughout the tunnel. Have a go at trying to match these features up on both sides of the cave! BGS © UKRI.

Joints in Park Tunnel

About midway into the tunnel you’ll see two large cracks that travel through both walls and the ceiling. These cracks are a type of joint. A geological joint is very similar to a fault, except that faults occur where one side of the rock has moved relative to the other. You can see in the tunnel that the layers are perfectly aligned either side of the crack, hence it is a joint.

You would naturally assume that having a joint in the rock is a huge risk that things might break or collapse, but not all joints are equal. Some, like this one, are likely weakening the rock slightly, but the rest of the sandstone is sufficiently strong enough to make up for this crack. It is very likely that the crack formed when the tunnel was originally dug.

The Ropewalk

It is well worth taking the stairs at the exit of the tunnel up onto a road called The Ropewalk. Climbing the steps gives a great impression of how thick the sandstone is; with each step, you are climbing up through the layers. The vantage point over The Ropewalk also offers the opportunity for great views into the Park Estate, but you can also see clearly the impact of the sandstone and how it shaped this part of the city. Make sure to let your gaze follow the sandstone cliffs that Park Tunnel is cut into, stretching around the Park Estate and looking to the south, where they line up with the cliffs at Nottingham Castle (Castle Rock), showing clearly it is all the same sandstone.

Lastly, it is worth noting that the ammonite present towards the stair end of the tunnel is in fact a poor attempt at geo-vandalism. Not a great attempt at a fossil and present in the wrong rock type: do not be confused by this poor imitation!

About the author

Dr Oliver Wakefield

BGS Regional Geologist, Midlands and East Anglia

You may also be interested in

Discovering Geology

Discovering Geology introduces a range of geoscience topics to school-age students and learners of all ages.

Maps and resources

Download and print free educational resources.

Postcard geology

Find out more about sites of geological interest around the UK, as described by BGS staff.