New study reveals long-term effects of deep-sea mining and first signs of biological recovery

BGS geologists were involved in new study revealing the long-term effects of seabed mining tracks, 44 years after deep-sea trials in the Pacific Ocean.

27/03/2025 By BGS Press

Concerns around deep-sea mining and its impact on the marine environment have been heightened by a lack of evidence and understanding of the long-term recovery of the deep-sea ecosystem once mining is finished. New research led by the UK National Oceanography Centre (NOC), with co-authors from scientific organisations including BGS, has been published in the scientific journal Nature, providing vital evidence in the global deep-sea mining debate.

A team of scientists, including BGS Senior Geoscientist Dr Hannah Grant and Dr Pierre Josso, deputy director of the UK Critical Minerals Intelligence Centre, visited the Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ) in 2023 to investigate a test mining site from 1979. This site provides an opportunity to investigate potential timescales for recovery and what traces remain 44 years after the mining machinery left.

BGS geologists provided sedimentological analysis and studied video footage of the seabed to assess the physical geological changes resulting from deep-sea sediment disturbance during the mining test. The results showed that the mining caused long-term changes to the sediments due to its propulsion design, which is quite distinct from today’s collector system designs, but that the long-term effects on the fauna living at these depths is variable.

With this research, BGS geologists are adding to the deep-sea environmental evidence base. We are assessing both the short- and long-term effects of deep-sea mining in order to inform policymakers.

Dr Hannah Grant, BGS Senior Geoscientist.

This research provides a foundation for ongoing BGS work exploring the effects of disturbance by the release of metals into sea water and how rapidly areas affected by such disturbance recover to their previous state.

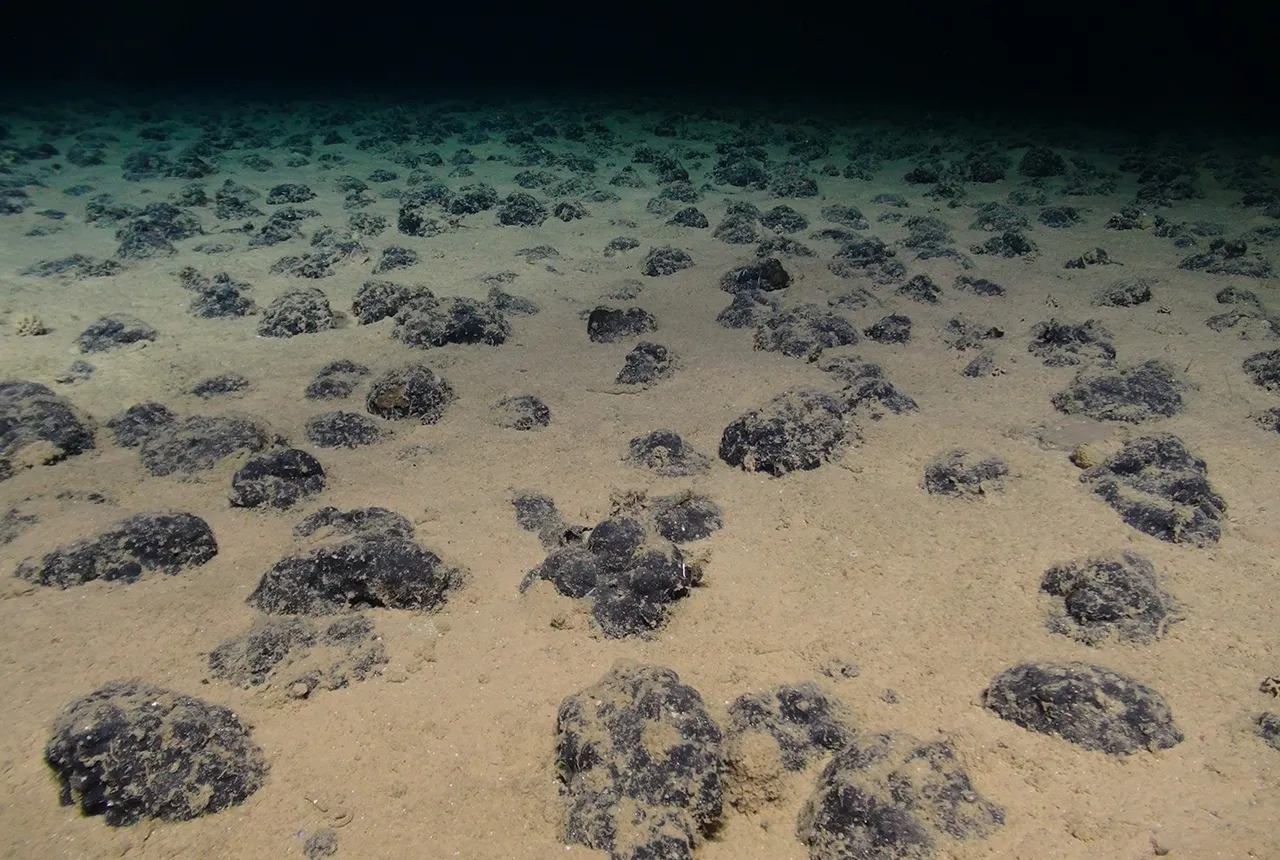

To tackle the crucial question of recovery from deep-sea mining, we need first to look to the past and use old mining tests to help understand long-term impacts. Forty-four years later, the mining tracks themselves look very similar to when they were first made, with an 8-metre-wide strip of seabed cleared of nodules and two large furrows in the sea floor where the machine passed. The numbers of many animals were reduced within the tracks but we did see some of the first signs of biological recovery.

We found some recovery of small and mobile animals living on the sediment surface. A type of large, amoeba-like xenophyophore, creatures commonly found everywhere in the CCZ region, had recolonised the track areas. However, large-sized animals that are fixed to the sea floor are still very rare in the tracks, showing little signs of recovery.

Prof Daniel Jones, lead author and expedition leader, NOC.

The team also discovered that sediment plumes, previously considered likely to have a major impact on the sea-floor community, had limited long-term physical impacts and no detectable negative effects on animal numbers in the study.

The evidence provided by this study is critical for understanding potential long-term impacts. Although we saw some areas with little or no recovery, some animal groups were showing the first signs of recolonisation and repopulation.

Prof Daniel Jones.

Deep-sea mining is increasingly being considered as a potential solution to supply the crucial metals required for advancing global technology and driving the transition to a net zero energy future. The CCZ, a vast region in the international waters of the central Pacific Ocean, is a key area of interest for mining. Spanning over 6 million km2, it is approximately 25 times the size of the UK and is home to unique and biodiverse deep-sea creatures, many yet to be described by science. It is also a rich mineral resource of polymetallic nodules, highly enriched in metals. At depths of nearly 5000 m on the seabed of the CCZ, the abundant, potato-sized rocks represent one of the most promising deep-sea mineral resources.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA), established in 1994 under international law, is deciding whether to allow deep-sea mining in the region and under what conditions. A key question in this decision is whether deep-sea ecosystems can recover from mining disturbances.

General ecological theory will predict that, following disturbance, any ecosystem will go through a series of successional stages of recolonisation and growth. However, until this study, we had no idea of the timescales of this critical process in the deep-sea mining regions, or how different parts of the community respond in different ways.

Our results don’t provide an answer to whether deep-sea mining is societally acceptable, but they do provide the data needed to make better-informed policy decisions such as the creation and refinement of protected regions and how we would monitor future impacts.

Dr Adrian Glover, study co-author, Natural History Museum.

The first industrial trials of deep-sea mining were carried out in the Pacific Ocean in the 1970s and Prof Jones and his team visited this site in 2023 to explore and study the aged mining tracks. The team reached the site on board the world-class RRS James Cook, which is equipped with the cutting-edge underwater robot submersible Isis.

The study forms part of the NOC-led ‘Seabed mining and resilience to experimental impact’ (SMARTEX) project, funded by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC). All the data collected is made available to all stakeholders in order to guide future policy decisions by the ISA and the nation states involved.

Related news

Map of BGS BritPits showing the distribution of worked mineral commodities across the country

18/02/2026

BGS’s data scientists have generated a summary map of the most commonly extracted mineral commodities by local authority area, demonstrating the diverse nature of British mineral resources.

Funding awarded to map the stocks and flows of technology metals in everyday electronic devices

12/02/2026

A new BGS project has been awarded Circular Electricals funding from Material Focus to investigate the use of technology metals in everyday electrical items.

New UK/Chile partnership prioritises sustainable practices around critical raw materials

09/02/2026

BGS and Chile’s Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería have signed a bilateral scientific partnership to support research into critical raw materials and sustainable practices.

Extensive freshened water confirmed beneath the ocean floor off the coast of New England for the first time

09/02/2026

BGS is part of the international team that has discovered the first detailed evidence of long-suspected, hidden, freshwater aquifers.

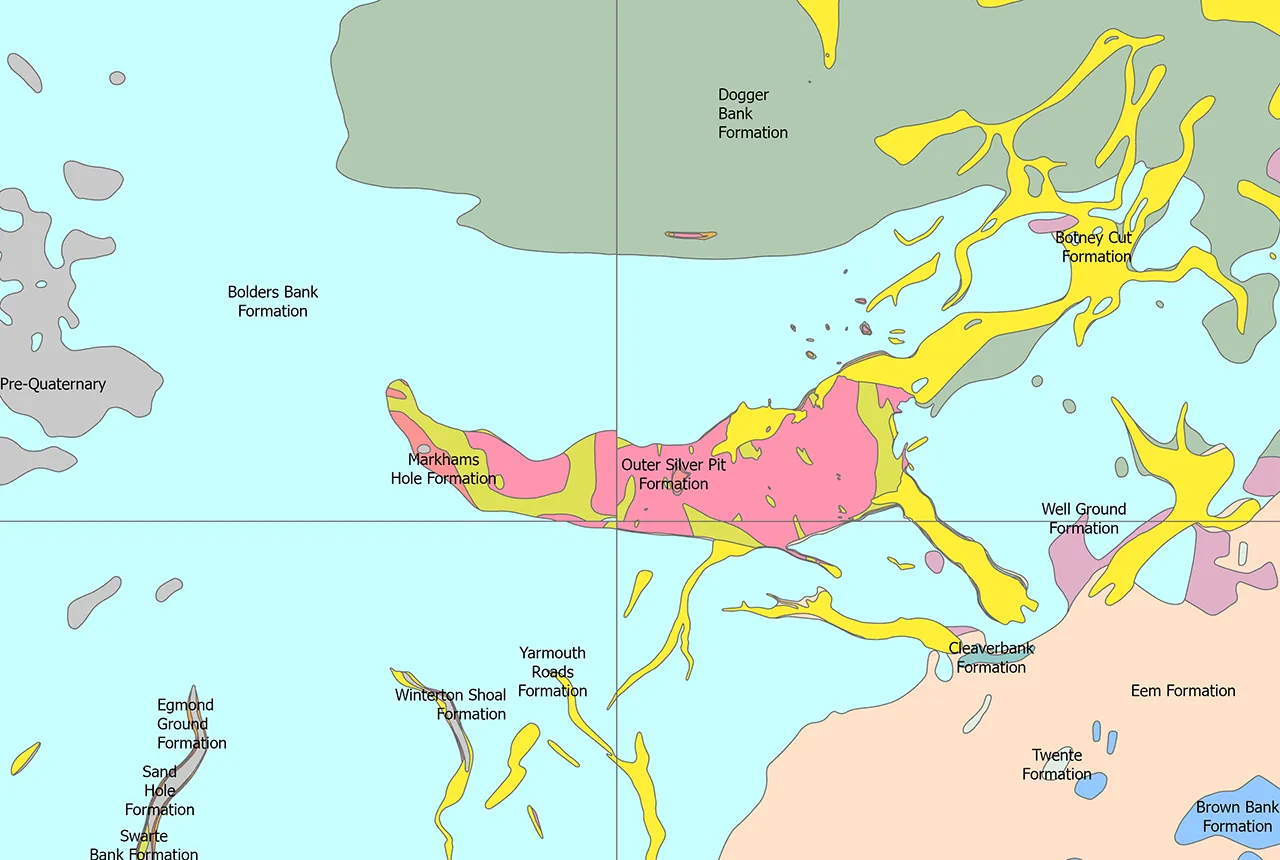

Quaternary UK offshore data digitised for the first time

21/01/2026

The offshore wind industry will be boosted by the digitisation of a dataset showing the Quaternary geology at the seabed and the UK’s shallow subsurface.

Hole-y c*@p! How bat excrement is sculpting Borneo’s hidden caves

23/12/2025

BGS researchers have delved into Borneo’s underworld to learn more about how guano deposited by bats and cave-dwelling birds is shaping the subsurface.

BGS awarded funding to support Malaysia’s climate resilience plan

17/12/2025

The project, funded by the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, will focus on minimising economic and social impacts from rainfall-induced landslides.

BGS agrees to establish collaboration framework with Ukrainian government

11/12/2025

The partnership will focus on joint research and data exchange opportunities with Ukrainian colleagues.

New 3D model to help mitigate groundwater flooding

08/12/2025

BGS has released a 3D geological model of Gateshead to enhance understanding of groundwater and improve the response to flooding.

Scientists gain access to ‘once in a lifetime’ core from Great Glen Fault

01/12/2025

The geological core provides a cross-section through the UK’s largest fault zone, offering a rare insight into the formation of the Scottish Highlands.

New research shows artificial intelligence earthquake tools forecast aftershock risk in seconds

25/11/2025

Researchers from BGS and the universities of Edinburgh and Padua created the forecasting tools, which were trained on real earthquakes around the world.

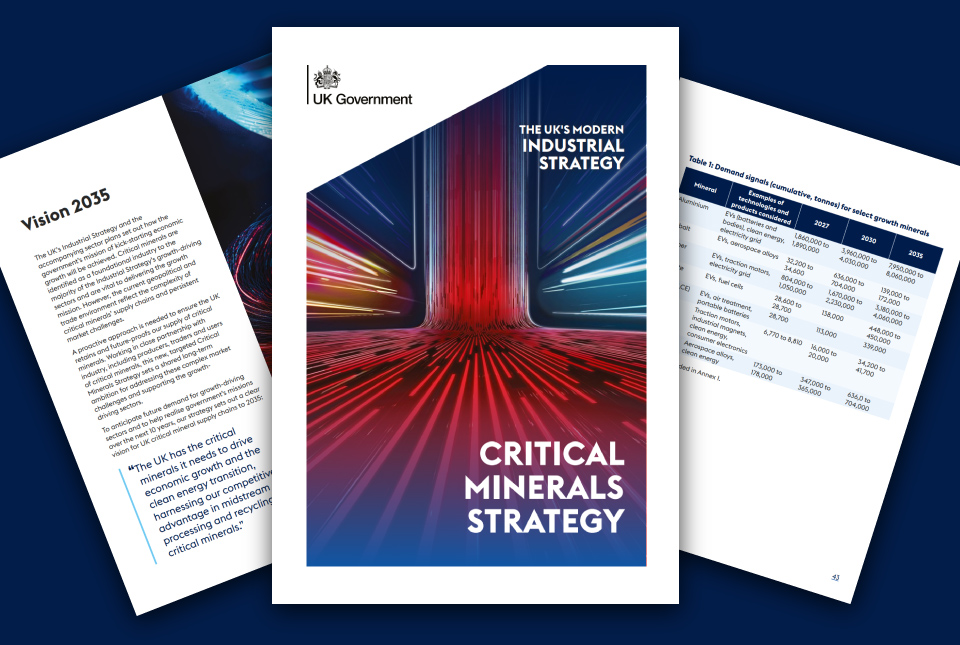

BGS welcomes publication of the UK Critical Minerals Strategy

23/11/2025

A clear strategic vision for the UK is crucial to secure the country’s long-term critical mineral supply chains and drive forward the Government’s economic growth agenda.