Climate change and human exploitation linked to historic decline in Atlantic salmon

New research reveals that both a change in climate and human exploitation played a role in a decline in North Atlantic salmon populations.

08/06/2022 By BGS Press

New research has revealed that an abrupt change in climate conditions in the North Atlantic around 800 years ago played a role in a decline in Atlantic salmon populations returning to rivers. Human exploitation reduced their populations still further.

Using state-of-the-art geochemistry, a team of scientists has discovered that large-scale changes in the marine habitat, brought on by a transition from a warm to a cold climate and what is now known as the Little Ice Age (approximately 1300 to 1850 CE), corresponded with a decline in salmon in the River Spey, Scotland. The study, published in the international journal The Holocene, was led by the University of Southampton, working with BGS.

These results can help us understand some of the controls on salmon populations prior to and during major human exploitation.

Our study shows that historically, beavers – common in Scotland hundreds of years ago – do not appear to have significantly impacted salmon numbers. This is very relevant today, as the animals are being reintroduced to UK rivers and a debate continues about their potential impact on migratory species like salmon.

Prof David Sear, professor of geography and environmental science at the University of Southampton and lead author of the study.

This research benefited from state-of-the-art geochemistry which enabled us to fingerprint salmon abundance over hundreds of years. We show that climate has been an important influence of salmon numbers, which is very relevant today due to the speed of climate change.

Prof Melanie Leng, BGS, co-author.

Atlantic salmon lay their eggs in the gravels of headwater streams, where their young live for a year or two before migrating out to sea. Here, they feed and grow into adults, eventually returning to the river to spawn, where many then die. The sperm, eggs and carcasses are rich in marine nutrients, which can be detected in sediment hundreds of years later.

Using core samples from Loch Insh on the River Spey, the scientists collected and measured marine-derived nutrients (MDNs), which give an understanding of the historic population levels of salmon. The team also examined a 150-year record of net-catch data from the lower Spey to help calibrate the MDN record.

The scientists were able to construct a 2000-year record of both salmon-derived nutrients and variations in climate conditions.

The findings show:

- bigger salmon populations (inferred from changes in MDNs) in the past reduced during a cooling climate at around the same time humans began to exploit them, leading to a major decline in the fish over the last 800 years

- larger salmon populations in the past occurred at a time when rivers were also inhabited by beavers, which suggests migratory fish are capable of co-existing with beavers; this is an important concern of anglers around current beaver reintroductions

- migratory fish, such as salmon, bring marine nutrients into our nutrient-poor upland rivers and probably represented a major boost to aquatic and wetland ecosystems in the past, with a decline in nutrients negatively affecting these ecosystems today

It is the first study to use MDNs to measure Atlantic salmon, although the method has previously been used for Pacific salmon in north-west USA and Canada.

Relative topics

Related news

Funding awarded to UK/Canadian critical mineral research projects

08/07/2025

BGS is part of a groundbreaking science partnership aiming to improve critical minerals mining and supply chains.

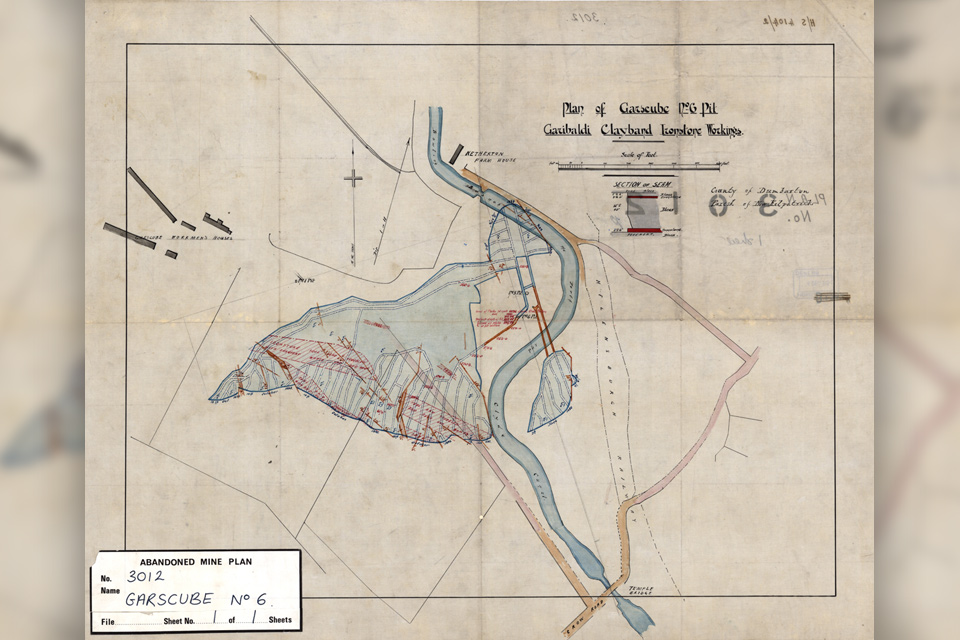

Release of over 500 Scottish abandoned-mine plans

24/06/2025

The historical plans cover non-coal mines that were abandoned pre-1980 and are available through BGS’s plans viewer.

New collaboration aims to improve availability of real-time hazard impact data

19/06/2025

BGS has signed a memorandum of understanding with FloodTags to collaborate on the use of large language models to improve real-time monitoring of geological hazards and their impacts.

Modern pesticides found in UK rivers could pose risk to aquatic life

17/06/2025

New research shows that modern pesticides used in agriculture and veterinary medicines have been found for the first time in English rivers.

Goldilocks zones: ‘geological super regions’ set to drive annual £40 billion investment in jobs and economic growth

10/06/2025

Eight UK regions identified as ‘just right’ in terms of geological conditions to drive the country’s net zero energy ambitions.

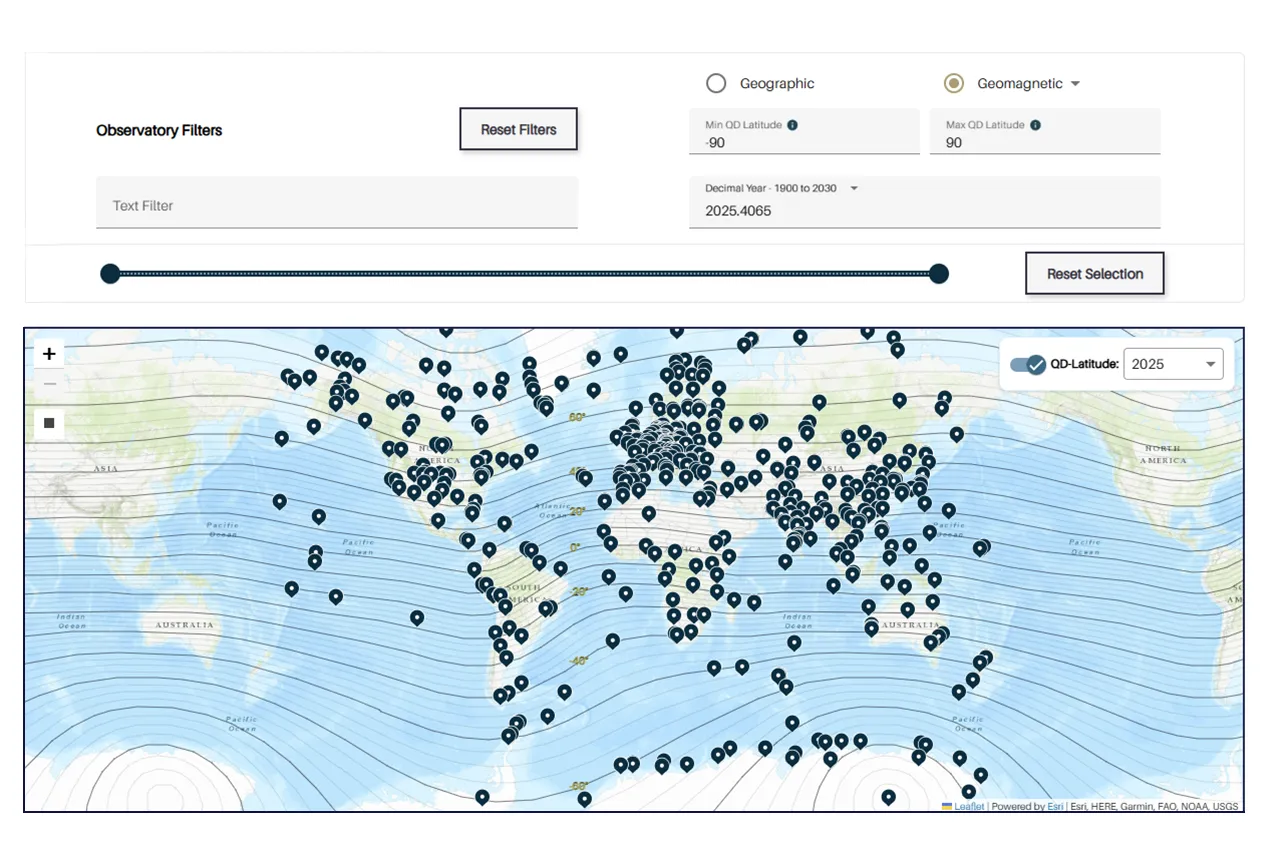

Upgraded web portal improves access to geomagnetism data

02/06/2025

BGS’s geomagnetism portal, which holds data for over 570 observatories across the world, has received a significant update.

BGS digital geology maps: we want your feedback

29/05/2025

BGS is asking for user feedback on its digital geological map datasets to improve data content and delivery.

What is the impact of drought on temperate soils?

22/05/2025

A new BGS review pulls together key information on the impact of drought on temperate soils and the further research needed to fully understand it.

UK Minerals Yearbook 2024 released

21/05/2025

The annual publication provides essential information about the production, consumption and trade of UK minerals up to 2024.

BGS scientists join international expedition off the coast of New England

20/05/2025

Latest IODP research project investigates freshened water under the ocean floor.

New interactive map viewer reveals growing capacity and rare earth element content of UK wind farms

16/05/2025

BGS’s new tool highlights the development of wind energy installations over time, along with their magnet and rare earth content.

UKRI announce new Chair of the BGS Board

01/05/2025

Prof Paul Monks CB will step into the role later this year.