Glaciers retreat; soils emerge – summer fieldwork at 79°N

Studying the evolution of newly emerging soils uncovered by retreating glaciers on the Svalbard archipelago in the Arctic Ocean.

14/09/2021

At the beginning of July 2021, the SUN-SPEARS project team embarked on its first fieldwork trip to Spitsbergen, the biggest island of the Svalbard archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. Electronic and instrumentation engineer Harry Harrison and I, waving the BGS flag, were lucky enough to be part of this contingent of researchers made up of biologists, environmental engineers and geophysicists.

Our ambition is to study the evolution of newly emerging soils uncovered by retreating glaciers. In order to achieve this, we installed an array of geophysical sensors on a glacier forefield at two different locations over soils of five and fifty years of age. We also collected a range of soil samples that will tell us more about the local biodiversity and how this varies between soils of different ages.

Ny-Ålesund research settlement

Located at a latitude of 79°N, Ny-Ålesund was our home for three weeks. It is a former mining town that is now dedicated entirely to Arctic research. The Governor of Svalbard, through Kings Bay company, operates the logistics behind the research stations, which belong to various countries including Norway, UK, France, Germany, Korea and Japan. Unfortunately, the pandemic prohibited the UK station from opening this year, but we were kindly hosted by our friends at Sverdrup, the Norwegian station. They provided valuable instructions, directions and, most importantly, radio communication.

Polar bear family seen through our binoculars. Harry Harrison, BGS © UKRI.

While out in the field we were in constant contact with the lookout on duty, who was responsible for letting us know of any potential dangers on site. This proved to be essential on one of our days out, when we had the exciting yet slightly terrifying experience of being notified that a mama polar bear and her two cubs were taking a break from their journey around the fjord and were right in our way back to town. Binoculars allowed us to spot them quite quickly and, with eyes on them at all times, we returned safe and sound by taking a substantial detour through the rolling moraines.

The Midtre Lovénbreen glacier

Towering near our fieldsite stands the very impressive glacier Midtre Lovénbreen (ML). It has lost almost one kilometre, a fifth of its maximum length, over the past 90 years due to global warming. It has left behind a large moraine dominated by glaciofluvial debris. Despite looking like a desolated, frozen land, among the loose rocks and sediments we were able to find soil. This is a mark of change, a mark of a new Arctic environment in the making, and it is precisely this soil’s formation and evolution that we are so curious about.

Sensor installations

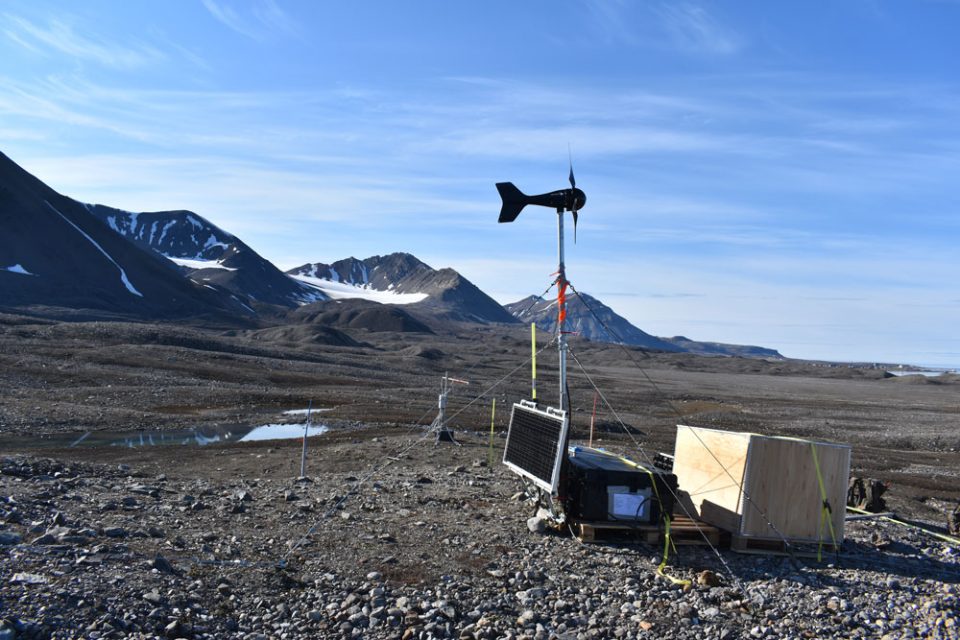

We left an array of electrodes and other soil sensors in the ground that will record soil temperature, moisture content and electrical resistivity. These parameters will give us an indication of how soil properties change on the moraine across the different seasons. For example, it will enable us to understand how quickly the soil freezing front progresses once subjected to below-zero air temperatures or how quickly the spring snow-melt infiltrates. Until now, this was unknown to the scientific community, researchers being unable to access these Arctic field sites in the winter due to the very harsh weather conditions.

We have left our instruments behind to measure for a whole year. Their batteries will hopefully be kept alive by the wind turbine and solar panel we also installed. With a bit of luck, we will find them as they are now when we return next summer, holding some very precious data that may be the key to uncovering some of the Arctic’s secrets.

One of the two sensor tower installations. Mihai Cimpoiasu, BGS © UKRI.

About the author

Dr Mihai Octavian, Cimpoiasu

Postdoctoral research associate, geophysics