Exploring Scotland’s hidden energy potential with geology and geophysics: fieldwork in the Cairngorms

BUFI student Innes Campbell discusses his research on Scotland’s radiothermal granites and how a fieldtrip with BGS helped further explore the subject.

31/03/2025 By BGS Press

As a geologist and geophysicist, my research focuses on understanding whether Scotland’s radiothermal granites could help unlock a new source of sustainable geothermal energy for the UK. In summer 2024, I conducted a three-week field campaign to study the potential for geothermal energy in the Cairngorms with a team of other geoscientists.

The Cairngorms: more than just mountains

Geothermal energy is often associated with places like Iceland or other volcanic hot spots, but Scotland’s ancient granites may also be able to supply sustainable heat. The Cairngorm Pluton, part of the East Grampians Batholith, is one of the UK’s highest heat-producing granites, with intriguing geothermal potential. My work combines geophysical surveying with laboratory experiments to explore this potential, whilst addressing uncertainties about the region’s geology.

Using magnetotellurics to explore below the surface

Magnetotellurics (MT) is a deep-sounding geophysical technique that uses the Earth’s natural electromagnetic field to produce images of the conductivity properties of the rocks in the subsurface. It can also be used to map features like fluid pathways and fractures located several kilometres below the surface. These pathways are critical for geothermal energy because they act as conduits for the fluids transporting heat.

Figure 2: The Phoenix MTU-5C Receiver during installation in Glen Einich. Photo reproduced with kind permission.

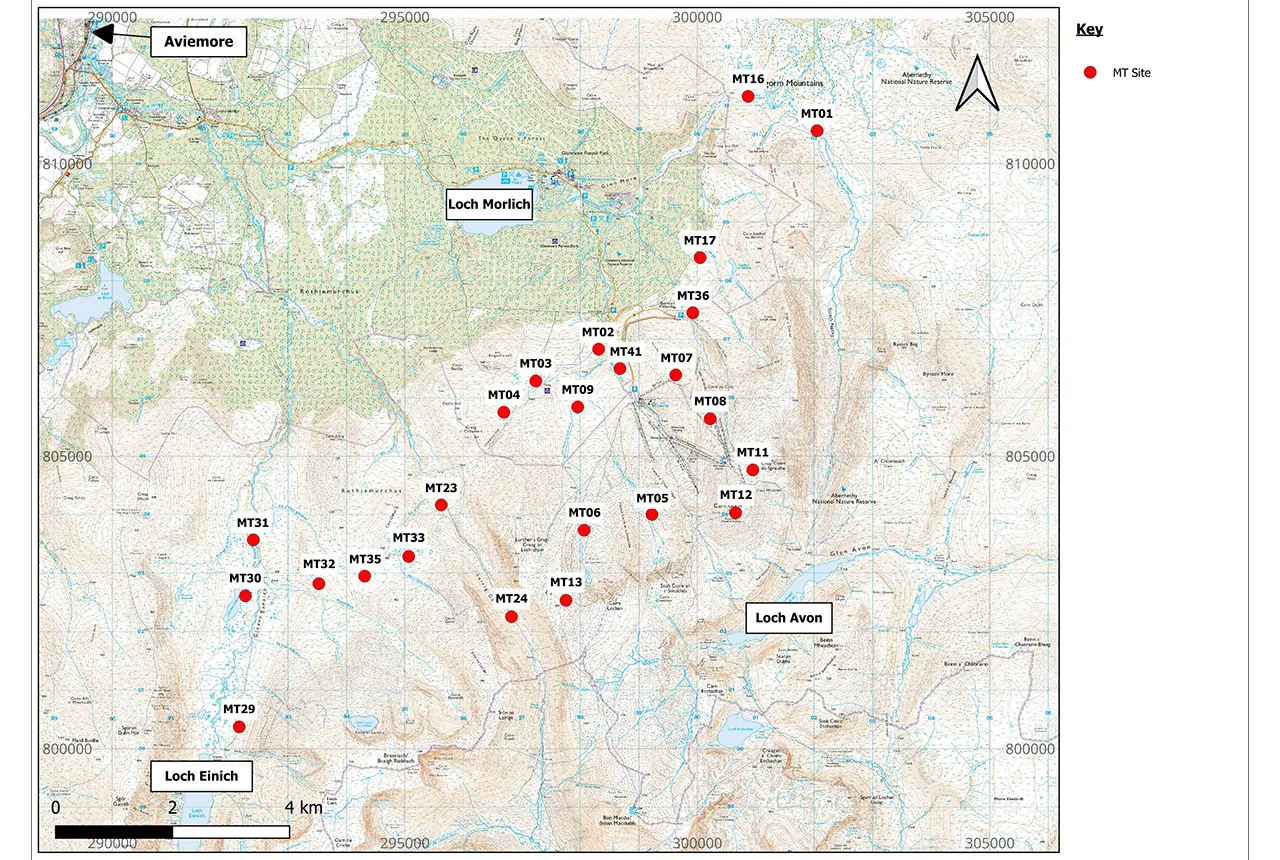

During my fieldwork in the Cairngorms, we set up 24 MT stations using instruments on loan from the NERC Geophysical Equipment Facility across the region. These were deployed by a team comprising myself and:

- BGS staff members

- Heriot-Watt University staff

- other postgraduate researchers

- a Cairngorm ranger

- a University of St Andrews undergraduate student

The MT equipment uses two types of sensor: (1) non-polarisable electrodes, which measure the ground electric field, and (2) induction coil magnetometers, which measure changes in the magnetic field. The setup at each site required us to bury the sensors to protect them from the fierce weather conditions.

Installation ~1km northwest of Cairngorm Mountain Centre. The solar panel is recharging the battery powering the system. Photo credit: Innes Hamilton.

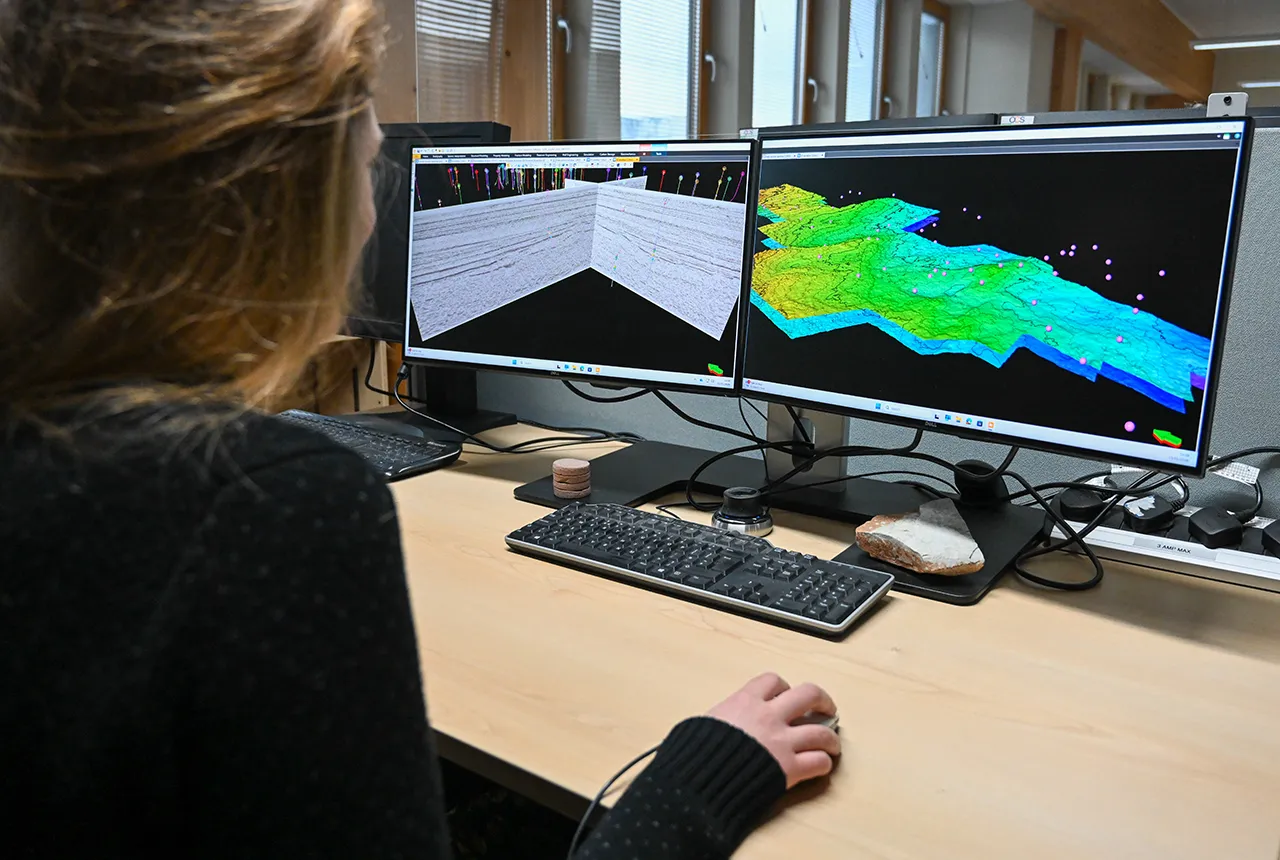

The data collected from the sensors will allow us to produce images of the Earth’s electrical resistivity below the surface using a mathematical process called data inversion. Ideally, the images could show zones with lower electrical conductivity, where fractures in the rocks are present within the resistive granite. These could be potential geothermal reservoirs from which heat can be extracted.

Map of all installed MT stations in the Cairngorms. Contains OS data © Crown Copyright and database right 2020.

Fieldwork challenges and discoveries

Conducting fieldwork in the beautiful but bleak Cairngorms is both rewarding and challenging. With no roads in much of the area, we had to carry our equipment, including a 20 kg battery, over many kilometres of hiking paths and sometimes beyond any trails. Navigating deep bogs, steep bouldery terrain and elevations of up to 1250 m while braving sudden weather changes was an adventure in itself. In June 2024 we had seven consecutive days of snow fall on the mountain!

Cairn Gorm summit weather station (1244 m) en route to MT installation site 12. Photo credit: Innes Campbell.

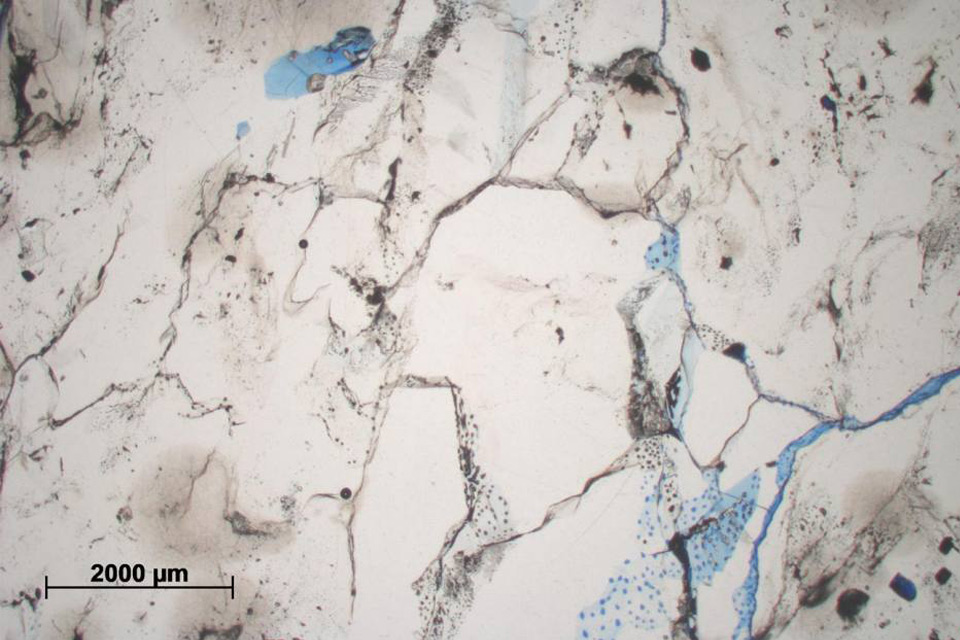

In addition to the MT fieldwork, I surveyed the geological structures and outcrops and collected samples for later laboratory analysis. One memorable moment came when we discovered a zone of extensive hydrothermal alteration of the granite near Stob Coire an t-Sneachda. This is possible evidence of hot fluids chemically changing the rock many millions of years ago. This alteration is significant because it could enhance the porosity and permeability of the rock, which are crucial factors for geothermal reservoirs.

Author on a hydrothermal alteration zone at Stob Coire an t-Sneachda. Photo reproduced with kind permission.

Why it matters

Geothermal energy offers a constant, low-carbon source of heat, making it a promising candidate for the UK’s renewable energy mix. Additionally, its small land footprint and minimal surface infrastructure requirements mean it can provide sustainable energy with reduced visual impact, preserving the natural landscape. My research aims to de-risk geothermal exploration in Scotland, providing the scientific basis for future projects that could benefit communities and combat climate change.

Instrumentation being carried between sites in Coire an t-Sneachda. Photo reproduced with kind permission.

Next steps

With my first year of fieldwork complete, I’m back in the laboratory, analysing samples and processing the MT data to build a three-dimensional resistivity map of the Cairngorm Pluton. Combining geophysical models with laboratory-based analyses will bring us closer to understanding the geothermal potential of this region of Scotland.

Thanks

Thanks go to Nathaniel Forbes Inskip and Andreas Busch from Heriot-Watt University and Juliane Huebert from BGS.

All images kindly reproduced with permission. For enquiries about the images within this article, please contact the copyright team (IPR@bgs.ac.uk).

Relative topics

Related news

MARC Conference 2025: highlighting the importance of conferences to PhD students

16/02/2026

BGS and University of Nottingham PhD student Paulina Baranowska shares her experience presenting her research on nuclear forensics at her first international conference.

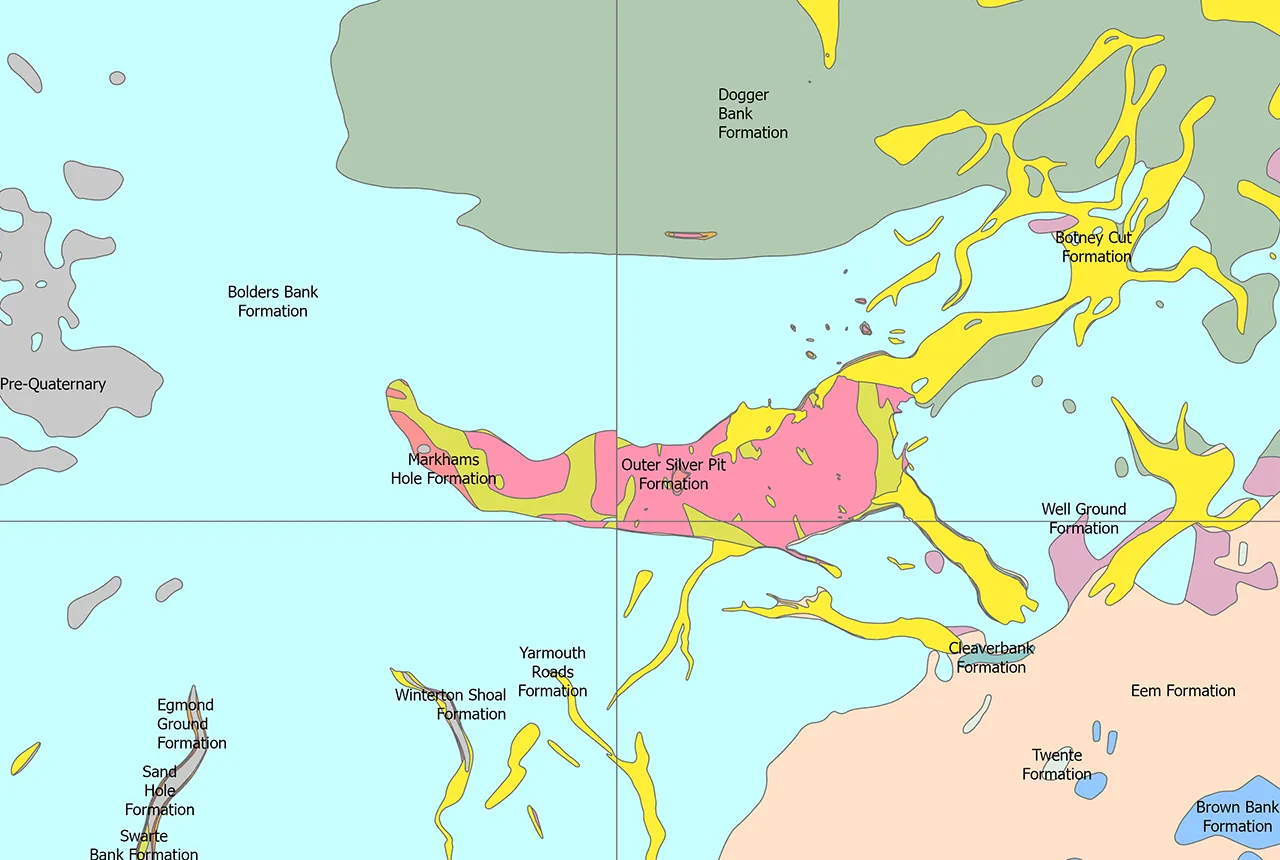

Can sandstones under the North Sea unlock the UK’s carbon storage potential?

02/02/2026

For the UK to reach its ambitious target of storing 170 million tonnes of carbon dioxide per year by 2050, it will need to look beyond the current well-studied geographical areas.

Quaternary UK offshore data digitised for the first time

21/01/2026

The offshore wind industry will be boosted by the digitisation of a dataset showing the Quaternary geology at the seabed and the UK’s shallow subsurface.

Making research matter: BGS joins leading research organisations in new national initiative

10/12/2025

A new alliance of 35 organisations has been formed that is dedicated to advancing science for the benefit of people, communities, the economy and national priorities.

Scientists gain access to ‘once in a lifetime’ core from Great Glen Fault

01/12/2025

The geological core provides a cross-section through the UK’s largest fault zone, offering a rare insight into the formation of the Scottish Highlands.

BGS welcomes publication of the UK Critical Minerals Strategy

23/11/2025

A clear strategic vision for the UK is crucial to secure the country’s long-term critical mineral supply chains and drive forward the Government’s economic growth agenda.

New funding awarded for UK geological storage research

21/11/2025

A project that aims to investigate the UK’s subsurface resource to support net zero has been awarded funding and is due to begin its research.

How the geology on our doorstep can help inform offshore infrastructure design

19/11/2025

BGS is part of a new collaboration using onshore field work to contextualise offshore data and update baseline geological models which can inform the sustainable use of marine resources.

First distributed acoustic sensing survey completed at UK Geoenergy Observatory

12/11/2025

New research at the Cheshire Observatory has shown the potential for mapping thermal changes in the subsurface using sound waves.

World Cities Day: the geological story of our cities

31/10/2025

Understanding the rocks that underlie our towns and cities, the risks they can present and how they influence urban planning and redevelopment.

Funding awarded for study on hydrogen storage potential in North Yorkshire

22/09/2025

A new study has been awarded funding to explore the potential for underground hydrogen storage near the Knapton power plant.

Opening up the geosciences: making work experience more accessible

19/09/2025

BGS has been working with partners to make the geosciences more accessible to young people, including those from under-represented backgrounds.