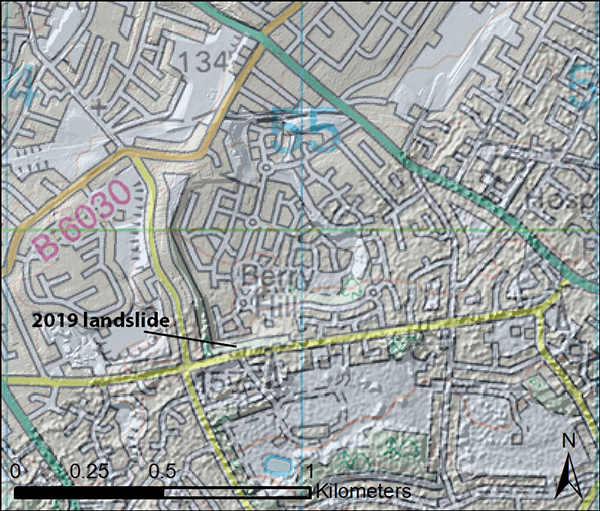

On 7 November 2019, a landslide occurred on a disused quarry slope in Mansfield in Nottinghamsire. The landslide affected over 35 properties; 60 people were evacuated and residents from 19 properties were unable to return to their homes for over two weeks.

The Berry Hill landslide and disused quarry slope taken from Bank End Close. BGS © UKRI.

Berry Hill housing estate

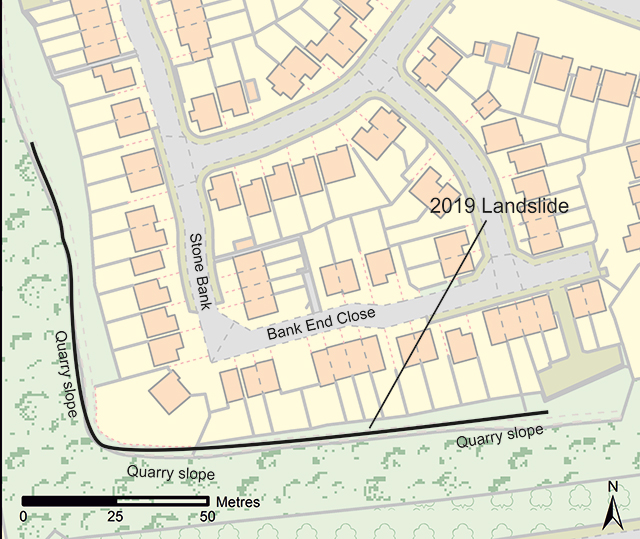

Between 2003 and 2011, the Berry Hill housing estate was built in the bottom of a former sandstone quarry, with Bank End Close and Stone Bank constructed nearest to the disused quarry slope. Some of the houses of Bank End Close are positioned 15–19 m away from the 25 m-high quarry slope within which this landslide occurred. Mansfield District Council reported that the gardens extend to the base of the slope, with a 3 m exclusion zone designed to accommodate small-scale block failures and localised washouts and slumps.

Landslide

The landslide on 7 November 2019 was not any of these landslide types; rather it initiated possibly as a block fall in the upper part of the slope followed by (what was caught on video) an earth/debris flow that, in turn, caused further failure in the underlying, weathered Chester Formation. It is also possible that the landslide was initiated by failure in superficial deposits, which may have been overhanging the underlying bedrock. It ran out approximately 17 m from the cliff, bringing trees and other vegetation down with it. The debris covered nearly all of the rear gardens of three properties.

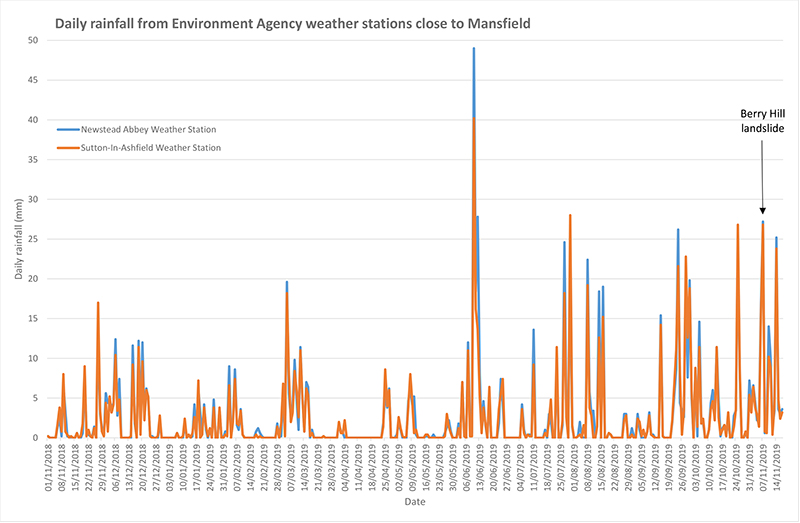

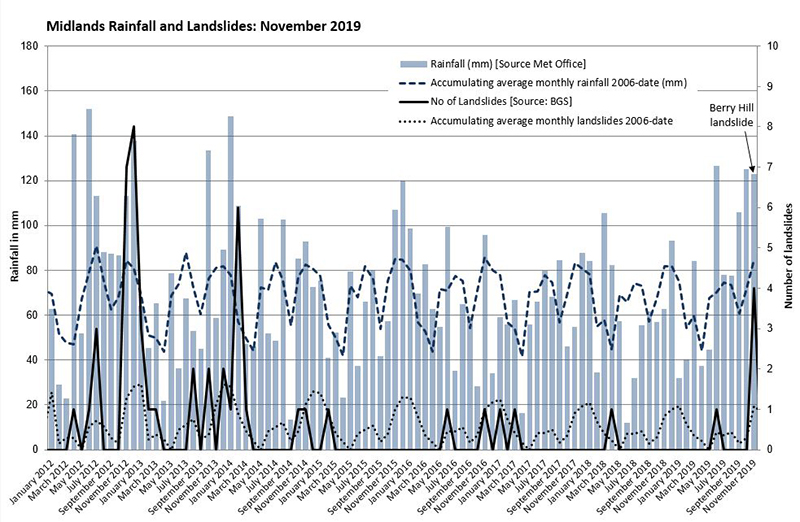

The landslide occurred after a period of intense rainfall as well as six months of above average rainfall, also experienced by the wider Midlands region. This rainfall caused widespread flooding across several regions of England, including Yorkshire and the Humber, the Midlands and the South.

Media reports

The landslide was reported widely in the media and part of the landslide was caught on video.

- UK flooding: aerial footage shows Mansfield landslide aftermath BBC, 8 November 2019

- Furious residents demand answers after Mansfield Quarry collapse Mansfield Chad, 8 November 2019

- Mansfield mudslide: residents ‘homeless for weeks’ BBC, 13 November 2019

- Mansfield mudslide was ‘completely unforeseen’ Nottingham Post, 16 November 2019

BGS response

The BGS Landslide Response Team was asked by the Resilience and Emergencies Division of the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government to provide assistance to Mansfield District Council, who are managing the site. We visited the landslide on 18 and 19 November 2019 to carry out a walkover survey and LiDAR scan of the landslide and surrounding area. The landslide has been entered into the BGS National Landslide Database, ID 20744/1.

Mansfield District Council employed specialist consultants, Fairhurst, to manage the removal of the landslide debris (reported to us as approximately 1300 tonnes) and design a scheme to stabilise the slope.

From this brief survey, it is clear that this is a complex situation and requires intrusive and detailed geological, geotechnical and hydrogeological analyses to understand the slope stability, taking into account the potentially highly varied depth of weathering in the sandstone, the hydrogeology of the area and the nature of the upper slope where the landslide initiated, including the overburden.

This BGS survey was carried out after the landslide debris had been removed and access to the upper slope was not possible. It is an independent and impartial assessment and is not related to the work that Fairhurst have undertaken on behalf of the Council.

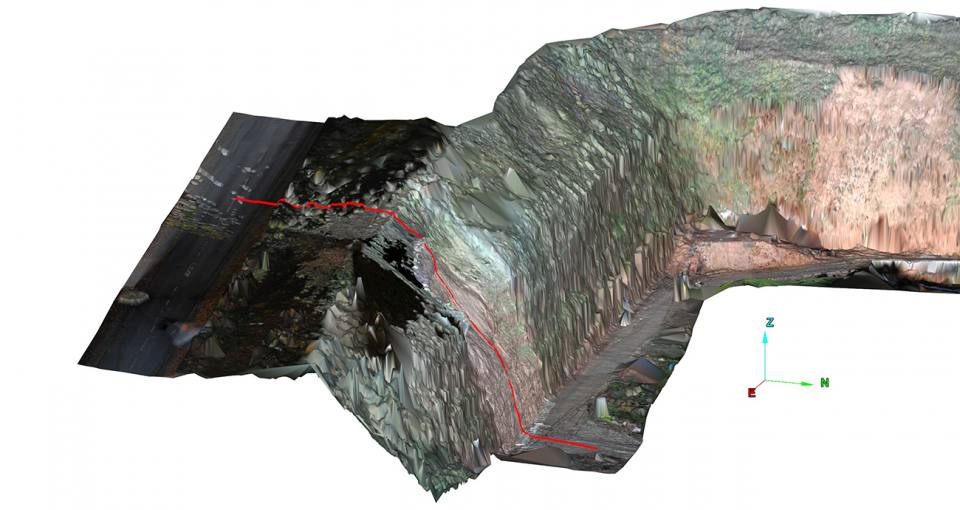

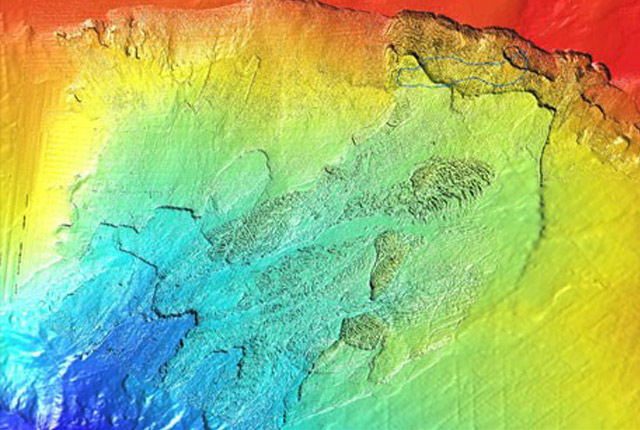

LiDAR survey

We carried out a terrestrial LiDAR survey using the Riegl VZ-1000. This survey comprised ten scans from eight locations totalling over 735 million data points. Six of these scans were captured within the quarry and two incorporate a section of the road above the quarry slopes on Berry Hill Lane. From this, we made 3D measurements and observations about the geology. Any future surveys can be compared with this baseline survey to determine change.

Figure 4: extent of LiDAR survey in Berry Hill quarry showing the landslide of November 2019. Note that the LiDAR survey was carried out after the landslide debris had been removed. BGS © UKRI

Geology

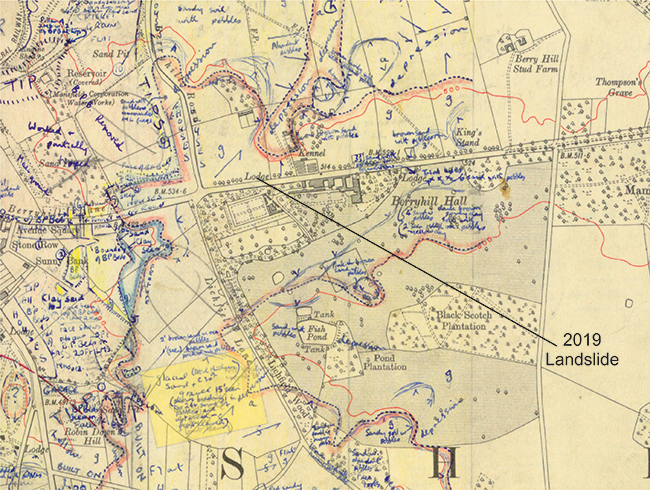

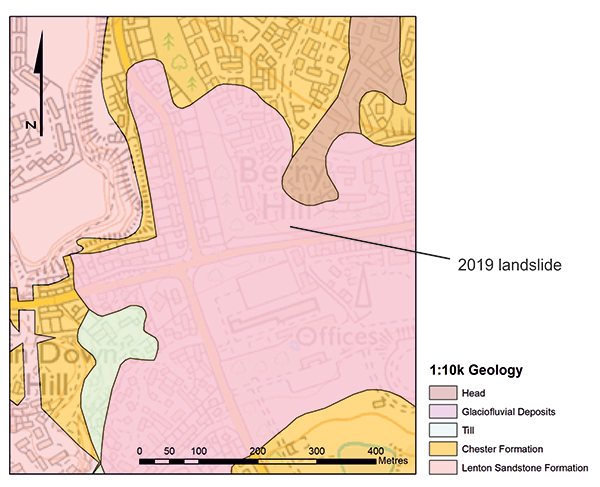

The geology in this area was mapped in the 1950s, before the quarrying took place. The current 1:10 000-scale geology map reflects this.

1:10 000-scale bedrock and superficial geology of the Berry Hill area before quarrying took place. BGS © UKRI.

Bedrock

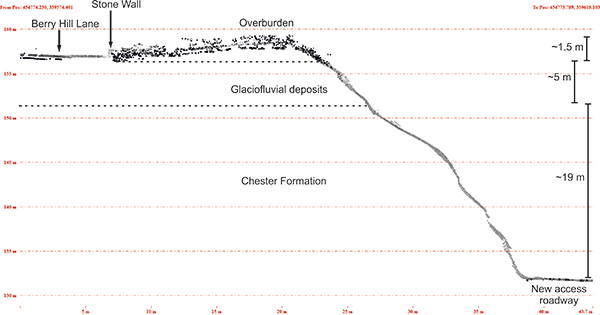

The cliff section at Berry Hill quarry is composed of Chester Formation (Triassic) sandstones (formerly been known as the Bunter Pebble Beds or the Nottingham Castle Formation) and is part of the Sherwood Sandstone Group. At the quarry, approximately 19 m is exposed in the slope.

Geological cross-section through the landslide after the debris had been cleared away. The land surface of this cross-section was taken from the LiDAR scan. The surface from the stone wall through the overburden shows some ‘noise’ caused by vegetation in this area. The depth of the overburden and glaciofluvial deposits are inferred from the LiDAR scan and what we observed visually from the ground. Borehole evidence is required to confirm this. BGS © UKRI.

Sherwood Sandstone Group

The Sherwood Sandstone Group exhibits a wide range of engineering properties (Yates, 1992) and rockfalls and landsliding are known to occur (Bell et al., 2009). In Nottinghamshire, it is often characterised as weak rock, containing extremely weak members; its strength decreases by 30–40 per cent when saturated (Sattler, 2018).

Weathering of the Chester Formation

Understanding the weathered state of the Chester Formation is an important factor when considering slope stability at the Berry Hill quarry site. This is because the rock is fundamentally weaker and more prone to breaking apart when weathered. According to Spink and Norbury (1990) the weathering of the Sherwood Sandstone Group is defined by the gradual disintegration from competent sandstone into loose sand.

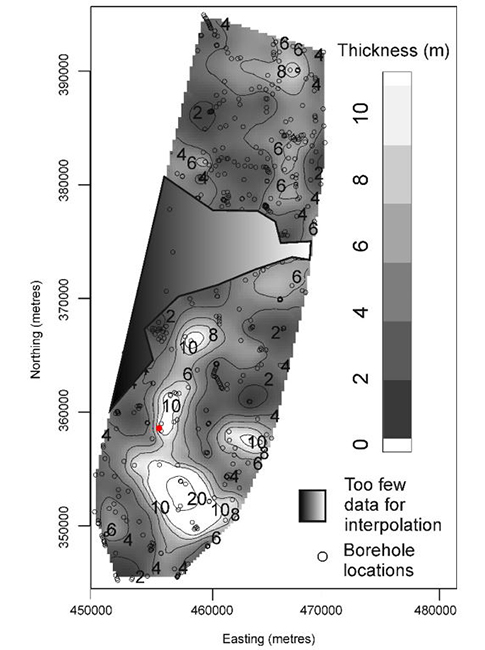

Map of thickness from the surface to competent rock in the Sherwood Sandstone Group outcrop in Nottinghamshire. Coordinates show metres of the British National Grid. The red dot shows the approximate location of the Berry Hill quarry landslide. BGS © UKRI.

Regionally, the average depth of weathering of the Sherwood Sandstone Group is generally between 4–6 m but this can extend locally to 40 m (Tye et al., 2011; 2012). In the case of the Berry Hill quarry landslide, the site (NGR 454764 359605) falls within the area of greatest weathering depth, as determined from a survey of over 500 borehole logs. These were used to produce the interpolated map of weathering thickness to competent rock.

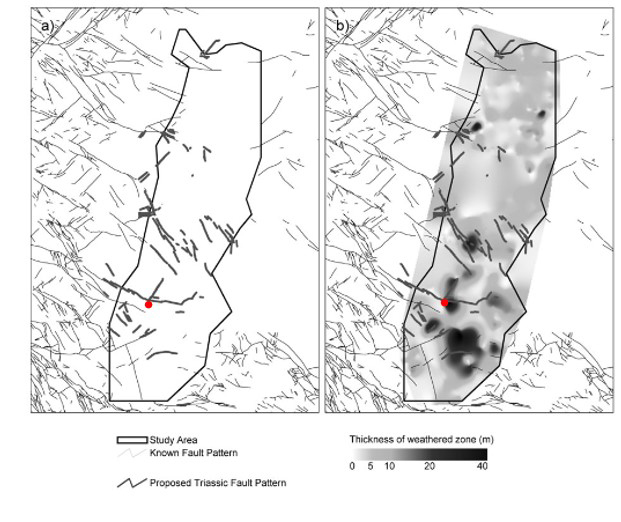

Whilst the upper depth of highly weathered soil (1–2 m depth) is determined primarily by freeze–thaw processes associated with the last glaciation, this deeper weathering leading to very weak rock is possibly linked to deep fracturing. This would potentially provide drainage pathways and cause greater removal of carbonate matrix cements in the rock.

Importantly, there is a high degree of spatial variability in the depth of weathering within the sandstone that is not necessarily visible at the rock face but can lead to changes in its chemical and physical characteristics.

Maps showing (a) known faulting in the Carboniferous strata underlying the Sherwood Sandstone Group outcrop and that faulting identified from the ‘coal abandonment plans’ where the throw is greater than 70 m and (b) the identified faulting pattern in the Carboniferous strata. BGS © UKRI.

Local Chester Formation lithology

Smith et al. (1967) describes a thick section of the Chester Formation from the adjacent former sand quarry (NGR 454520 359690) to the west of Berry Hill Road, approximately 250 m to the north-west of the landslide. There, the formation comprised a pale, pink-brown, cross-bedded, coarse-grained, pebbly sandstone.

The strata in Berry Hill quarry dip gently (approximately 1°) to the east. The Mansfield area lies in a transition zone where the formation begins to become less cemented and competent. To the south, the formation is comparatively well cemented and competent, whereas to the north it becomes less cemented and is essentially a sand. Within the Berry Hill quarry, the sandstone was observed to be weak.

Structure

The LiDAR survey shows the presence of jointing within the Chester Formation on the western wall of the quarry. Full analysis the data to identify areas of likely stress relief in the slope due to quarrying requires further analysis of the LiDAR survey and fieldwork, which are outside the time frame of this report.

Figure 9: jointing seen in the sandstone, particularly on the western quarry slope. BGS © UKRI.

Superficial deposits

The Chester Formation is overlain by mid Pleistocene-aged glaciofluvial deposits, which consists of loose, fine- to medium-grained sand and gravel. Thicknesses are likely to vary across the area, but a 5 m section, displaying imbrication and bedding, was observed towards the top of the sandstone cliff. This confirms the observations on the BGS field slip for the area (highlighted in yellow to the south-south-west of the site) and the corresponding extent of the glaciofluvial deposits on the published map sheet 112 (BGS, 1971).

Access to this part of the slope was not possible for this survey and much of the exposure of these deposits is obscured by vegetation. However, evidence for possible water seepage was seen at the base of these superficial deposits, although this could also have occurred if water ran down the surface of the more competent gravels leaving a surface expression in the softer sand drape below. Further investigation would be required to achieve a better understanding of the detailed extent and nature of these deposits.

Artificial ground

The top of the slope is composed of made ground in the form of dumped overburden from the quarry excavations. These deposits form a screening bund approximately 1.5 m high, running west–east to the north of Berry Hill Lane, and are composed of unsorted sand, gravel and topsoil. The cross-section shows this in profile.

Groundwater

The role of groundwater in this landslide is likely to be complex. We have not addressed this due to a lack of data and it requires further investigation.

References

BGS. 1971. Sheet 112 Chesterfield Solid and Drift. 1:50 000. (Keyworth, Nottingham: British Geological Survey).

Sattler, T. 2019. Implications on characterising the extremely weak Sherwood Sandstone: case of slope stability analysis using SRF at Two Oak Quarry in the UK. Geotechnical and Geological Engineering, Vol. 39, 1897–1918.

Smith, E G, Rhys, G H, and Eden, R A. 1967. Geology of the country around Chesterfield, Matlock and Mansfield. Memoir of the British Geological Survey, Sheet 112 (England and Wales).

Spink, T W, and Norbury, D R. 1990. The engineering geological description of weak rocks and over consolidated soils. 289–302 in The Engineering Geology of Weak Rock. Cripps, J C, Coulthard, J M, Culshaw, M G, Forster, A, Hencher, S R, and Moon, C F (editors). Proceedings of the 26th Annual Conference of the Engineering Group of the Geological Society, 9–13 Sept 1990, Leeds. (Rotterdam: Balkema.)

Tye, A M, Kemp, S J, Lark, R M, and Milodowski, A E. 2012. The role of peri-glacial active layer development in determining soil-regolith thickness across a Triassic sandstone outcrop in the UK. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, Vol. 37, 971–983.

Tye, A M, Lawley, R L, Ellis, M A, and Rawlins, B G. 2011. The spatial variation of weathering and soil depth across a Triassic sandstone outcrop. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, Vol. 36, 569–581.

Yates, P G J. 1992. The material strength of sandstones of the Sherwood Sandstone Group of north Staffordshire with reference to microfabric. Quarterly Journal of Engineering Geology, Vol. 25, 107–113.

You may also be interested in

Landslide case studies

The landslides team at the BGS has studied numerous landslides. This work informs our geological maps, memoirs and sheet explanations and provides data for our National Landslide Database, which underpins much of our research.

Understanding landslides

What is a landslide? Why do landslides happen? How to classify a landslide. Landslides in the UK and around the world.

How to classify a landslide

Landslides are classified by their type of movement. The four main types of movement are falls, topples, slides and flows.

Landslides in the UK and around the world

Landslides in the UK, around the world and under the sea.