Hole-y c*@p! How bat excrement is sculpting Borneo’s hidden caves

BGS researchers have delved into Borneo’s underworld to learn more about how guano deposited by bats and cave-dwelling birds is shaping the subsurface.

23/12/2025

Deep in the heart of the Borneo rainforest lies one of South-east Asia’s most important natural sites: the Gunung Mulu National Park of Sarawak, Malaysia. Despite being home to one of the most diverse tropical rainforests on the planet, arguably the world heritage area’s most astonishing feature lies underground.

The caves of the Gunung Mulu National Park

Under the limestone ridge of Gunung Api lies the extensive Clearwater cave system. At over 260 km in length and with passages often exceeding 30 m in diameter, it is believed to be the world’s largest cave system by volume, and is a haven for local wildlife.

The nearby Deer Cave is home to an estimated three million wrinkle-lipped bats, which fly out of the cave each evening to feed, creating a stunning visual display. Cave swiftlets also fly many kilometres into the Clearwater cave system to make their nests, which are prized as a local delicacy and used to make bird’s nest soup. Lying in wait to try and catch them as they fly past are cave racer snakes, whilst an astonishing array of cockroaches, millipedes, crabs, crickets and spiders are sustained by the piles of guano (bat poo) that line the cave floor. The ecosystem featured in a memorable episode of the BBC’s Planet Earth series.

History of the caves

Caves are fantastic repositories of geological and archaeological data, preserving information that would otherwise be lost to surface erosion and degradation. They and the deposits they contain hold clues to past landscape change, allowing us to reconstruct how the Earth’s surface has changed over millennia.

The caves were first explored as part of a Royal Geographical Society expedition in 1978. Working in collaboration with the Sarawak Forestry Corporation and the national park, the Mulu Caves Project has been exploring, surveying and undertaking research in the caves ever since. This includes caving expeditions led by Andrew Eavis, a veteran of the 1978 expedition.

Dating of stalagmites and cave sediments indicates the Mulu caves are up to three million years old. Other analysis of cave stalagmites has yielded a climate record spanning hundreds of thousands of years, whilst volcanic ash provides evidence of a massive volcanic eruption in the Philippines 189 000 years ago. More recent archaeological finds also provide evidence of human activity and burials in some of the caves.

Recent research within this incredible cave system led to a surprising discovery about the formation of the caves within it.

Unusual dissolution

One of the unusual aspects of the Mulu caves is the way the cave passages have been sculpted. Most caves in the region are formed by the dissolution (dissolving or break down) of limestone by acidic water, primarily from rivers flowing through the cave. The action of flowing water on the limestone rock creates small asymmetrical scoops etched into the passage walls, called scallops. These are preserved on the passage walls even after the formative river has abandoned the passage, as the water finds new, lower routes through the rock. The scallops are of interest to scientists as they can be used to deduce past water flow, providing a record of how water flowed through the caves over time.

In the Clearwater cave system, typical scallops are present in the lower levels of the cave system, close to the present river. However, in the older, higher levels of the cave system, which have long since been abandoned by the river, they are strangely noticeable by their absence, having been dissolved away and replaced by unusual corroded and pitted rock architecture.

The passage walls are frequently eroded into small dissolution pots and coated with a weathered crust: analysis has shown these are composed of calcium phosphate minerals, which is highly unusual in caves. Corroded stalagmites are common, dissolved away like rotten teeth to reveal their internal growth rings. These features suggest some form of atmospheric dissolution of the passage walls and stalagmites has taken place in the time since the passage was abandoned by the underground river.

Corroded stalagmite in Racer Cave, Mulu, revealing internal growth banding. © A R Farrant.

Guano pots on a limestone boulder, with a pale calcium phosphate weathering crust. Case is 20 cm long. © A R Farrant

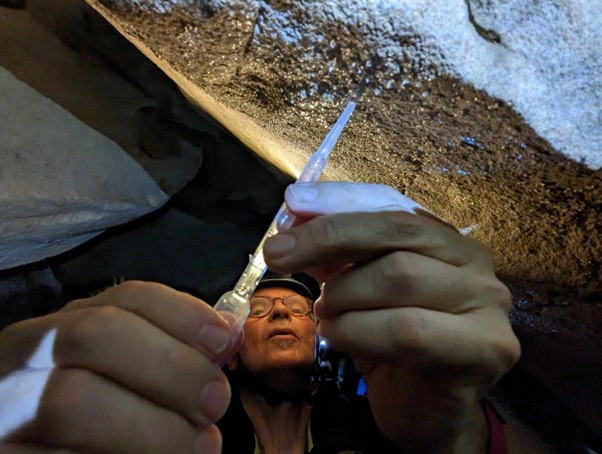

Comparison with other caves suggests these features are generally restricted to tropical cave systems. One of the key aims of recent Mulu expeditions has been to understand how these features form and why. A team of researchers led by BGS geologist Dr Andrew Farrant, cave microbiologist Prof Hazel Barton (University of Alabama), her PhD student J Max Koether and BGS isotope geochemist Dr Andi Smith set out to investigate what may be happening.

Caving and exploration

Undertaking cave research can be hard work. Sampling trips into a cave system over 250 km long takes time and, in some cases, involved making camp underground. It is hard, sweaty, sometimes muddy work, occasionally requiring ropes to climb up pitches or descend vertical drops. But the rewards are enormous: the caves are spectacular, with stunning formations, huge chambers and amazing biota.

The Clearwater streamway is probably one of the finest cave passages in the world. Not only is there the prospect of new scientific discoveries, but also the chance to explore new cave passages where no human has ever trodden. On one trip, the team crawled through a flat-out squeeze to emerge into an undiscovered chamber over 200 m long, 70 m wide and 50 m high (big enough to hold two Airbus A380 jets) and adorned with 20 m-high stalagmites.

Crossing the Clearwater River in the Clearwater cave system. © Christos Pennos

Research

Complex ecosystems are a distinctive feature of tropical caves, driven by the daily input of guano from bats and swiftlets. Bats create large piles of pungent excrement beneath their roosts, whilst the swiftlets’ guano is dispersed more widely, sometimes kilometres into the caves. The teams’ initial hypothesis was that the guano was somehow implicated in creating the unusual dissolution forms and smooth walls seen in the caves. Initial analysis of the guano piles in the caves indicated that they are strongly acidic, comparable to stomach acid or lemon juice, with a pH as low as 1.9. This could account for dissolution beneath the guano pile, but not the pervasive dissolution features seen throughout the caves.

Further work on the microbiology of the guano showed that microbial breakdown of urea (from bats) and uric acid (from birds) generates significant quantities of ammonia and carbon dioxide, which are released into the cave air. Measurable plumes of ammonia can be detected in some caves; could this be responsible for the unusual features?

Attention turned to the weathered ‘paste’ seen on many passage walls. This turned out to be teeming with microbial life, in some places containing a higher microbial cell count than cultured yogurt. Analysis of condensation water droplets on the cave walls revealed extraordinarily high levels of nitrate (up to 7000 mg/l; for comparison, the UK drinking water standard is 150 mg/l), whilst drips feeding the stalagmites had little or no nitrate.

These observations suggest that ammonia released into the cave air by the microbial decay of bat and bird guano adsorbs onto water droplets on the passage walls and stalagmites. Here, microbes use the ammonia as a food source, producing nitrates, nitric oxide, nitrogen dioxide and nitric acid as byproducts. This acid dissolves the passage walls and stalagmites, removing the original dissolutional scallops and replacing them with a suite of biogenic dissolution features. It is estimated that, in some places, several metres of dissolution have occurred in just a few tens of thousands of years: geologically speaking, this is a very short time period.

Further work is ongoing to learn more about the microbial processes that occur within the guano and on the cave walls. The discovery of this novel mechanism of cave development has significant implications, such as how we interpret past environments from caves, the preservation of cave art, and the impact of this acidic environment on ropes and other caving equipment.

Passage in Lagang’s Cave. The smooth bedrock fins on the left have undergone secondary microbial dissolution from nitric acid, whilst the right side, washed by a film of water, has abundant original fluvial scallops due to removal of ammonia and associated wall rock microbial communities. © Chris Howes

The great thing about the Mulu Caves Project expeditions is they have enabled us not just to explore new caves, but to do some amazing science too. One thing is clear from our work in the caves; the surface and underground environments are inextricably linked. There is much we still have to discover and one wonders what other secrets are waiting to be discovered beneath Gunung Api…

Publication

Our research has been recently published in the journal Geomorphology.

Farrant, A R, Koether, J M, Barton, H A, Lauritzen, S E, Pennos, C, Smith, A C, White, J, McLeod, A, and Eavis, A J. 2025. Pervasive speleogenetic modification of cave passages by nitrification of biogenic ammonia. Geomorphology, Vol. 483, 109822. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2025.109822

Thanks

Thanks go to Andrew Eavis and members of the Mulu Caves Project, the Sarawak Forestry Corporation and the Gunung Mulu National Park management and staff, without whom this work would not have been possible. Part of the research was funded by a NEIF steering committee grant to Andi Smith.

About the author

Dr Andrew Farrant

Geologist and karst geomorphologist

Relative topics

Related news

PhD adventures in Copenhagen, Denmark: revealing past recovery processes of tropical forest systems through ancient environmental DNA

12/03/2026

PhD student Chris Bengt visited the University of Copenhagen to carry out very delicate extraction of aeDNA from lake-sediment cores, in the hopes of unlocking the secrets of past volcanic eruptions.

New UK/Chile partnership prioritises sustainable practices around critical raw materials

09/02/2026

BGS and Chile’s Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería have signed a bilateral scientific partnership to support research into critical raw materials and sustainable practices.

Extensive freshened water confirmed beneath the ocean floor off the coast of New England for the first time

09/02/2026

BGS is part of the international team that has discovered the first detailed evidence of long-suspected, hidden, freshwater aquifers.

Hole-y c*@p! How bat excrement is sculpting Borneo’s hidden caves

23/12/2025

BGS researchers have delved into Borneo’s underworld to learn more about how guano deposited by bats and cave-dwelling birds is shaping the subsurface.

BGS awarded funding to support Malaysia’s climate resilience plan

17/12/2025

The project, funded by the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, will focus on minimising economic and social impacts from rainfall-induced landslides.

‘Three norths’ set to leave England and not return for hundreds of years

12/12/2025

The historic alignment of true, magnetic, and grid north is set to leave England, three years after they combined in the country for the first time since records began.

BGS agrees to establish collaboration framework with Ukrainian government

11/12/2025

The partnership will focus on joint research and data exchange opportunities with Ukrainian colleagues.

New research shows artificial intelligence earthquake tools forecast aftershock risk in seconds

25/11/2025

Researchers from BGS and the universities of Edinburgh and Padua created the forecasting tools, which were trained on real earthquakes around the world.

UK braced for what could be the largest solar storm in over two decades

12/11/2025

Intense geomagnetic activity could disrupt technology such as communication systems, global positioning systems and satellite orbits.

New research highlights significant earthquake potential in Indonesia’s capital city

04/11/2025

Research reveals that a fault cutting through the subsurface of Jakarta could generate a damaging earthquake of high magnitude.

Fieldwork on Volcán de Fuego

13/10/2025

Understanding how one of the world’s most active volcanoes builds up material, and how they collapse to feed hot flows

UK scientists in awe-rora as national coverage of magnetic field complete for the first time

23/09/2025

New sensors being installed across the UK are helping us understand the effects that extreme magnetic storms have on technology and national infrastructure.