Groundwater’s role in the current drought

Groundwater can play a vital part in keeping the UK’s water supply flowing, but we need to ensure that we monitor levels and rates of extraction during dry spells.

15/08/2022 By BGS Press

During the summer of 2022 concern for water resources has focused on heatwaves and the lack of rainfall. These factors combine to cause low flows in rivers, low stocks in reservoirs and increased demand for water. One aspect of the drought that has received less attention is groundwater.

The importance of groundwater

Groundwater plays an important role in water supply in the UK, both for agriculture and irrigation and for public supply:

- nationally, 30 per cent of public supply comes from groundwater

- this rises to 50 per cent in the south-east of England

- in some localised regions, 100 per cent of public supply is from groundwater

Just as important is groundwater’s role in sustaining flows in rivers and to wetlands during dry conditions. Although dry weather may cause winterbournes — streams that flow only after wet weather, usually in limestone or chalk areas — to naturally dry up, it is during drought we appreciate just how essential groundwater is. BGS works in partnership with environmental regulators and the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology to regularly assess the status of groundwater stocks and forecast how we expect them to respond in the future.

Since groundwater is out of sight below the ground it receives less attention than rivers, lakes and reservoirs. However, there is another reason for the current lack of attention; at the time of writing, groundwater in the UK has not yet been affected by the drought to the same extent as surface water and it’s helping bridge the supply gap left by the lack of rainfall that is affecting surface-water reservoirs.

Groundwater’s relationship with rainfall

Aquifers act as natural reservoirs that fill (recharge) from rainfall in wet winter months. During the summer, rainfall doesn’t normally reach the aquifers because any rain is taken up by wetting the soil, growing vegetation, or evaporating back to the atmosphere. Water that has been stored in these aquifers during winter can be drawn upon in dry summer months, providing an important and secure source of water in dry conditions. We are fortunate that even the driest parts of the UK, in the south and east of England, are underlain by a productive Chalk aquifer (the Chalk Group).

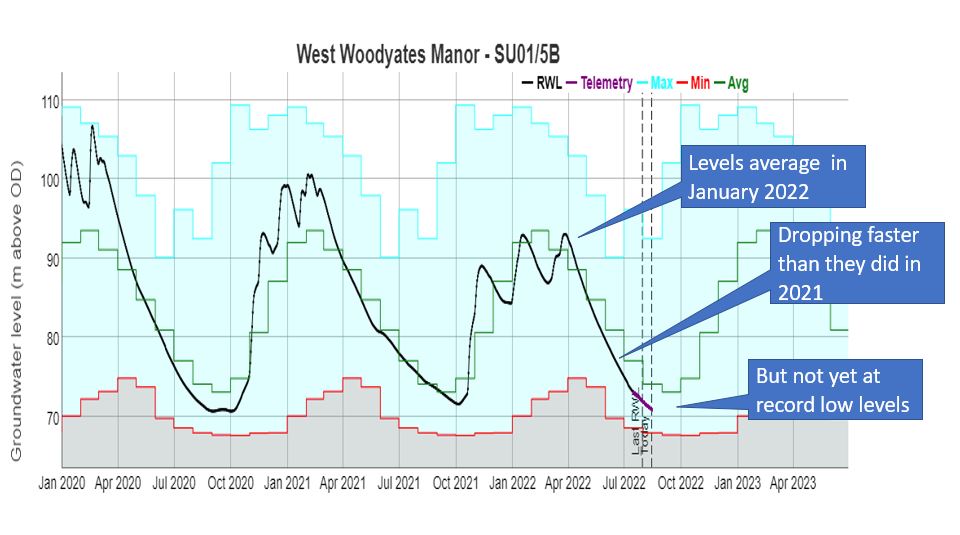

Record of levels at West Woodyates Manor, an observation well in Dorset. The graph shows the observed water level and the minimum, maximum and average levels for each calendar month. BGS © UKRI.

The situation in 2022

Last year (2021) was an average year for rainfall in the UK and, at the start of 2022, groundwater levels in the UK’s largest aquifers were also at average levels. The dry spring of 2022 meant that aquifers stopped filling from winter recharge earlier than they normally would and levels have fallen during the summer slightly faster than normal. Although levels are now at below normal to notably low levels in parts of the UK, they aren’t yet exceptionally low, except along the coast in the south-east of England and in South Wales. Aquifers here have relatively low storage and respond rapidly to rainfall, or a lack of rainfall. We publish a monthly Hydrological Summary that reviews the status of rivers and groundwater.

How low groundwater levels affect the environment

The impact of low groundwater levels is first felt in two ways. Outflow to rivers is reduced, particularly those rivers that depend most on groundwater. Bourne streams in Chalk areas are an extreme example; the upper part of the stream will dry in a normal summer, but this year even more of their length will be dry. Secondly, low groundwater levels mean there is reduced water availability for abstraction.

The Hughenden Stream, a tributary of the River Wye, is an intermittent chalk stream that only flows when groundwater levels in the surrounding Chiltern Hills are high enough. © Copyright Des Blenkinsopp and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

Could this affect water supply?

Larger sources used by water companies for public supply are usually sited in the parts of the aquifers where groundwater supplies are most resilient and reliable, so they aren’t affected in the early part of a drought. Smaller supplies for isolated communities, individual households and farming are often in less productive parts of aquifers and their yield can reduce or ultimately dry up.

Large public supplies tend to be affected in the later stages of a drought. Groundwater is managed in the UK under a system of abstraction licences; the total amount of water that can be extracted from an individual aquifer is controlled to ensure supplies are shared between users and to minimise the effect of pumping on rivers and wetlands. In England, this is undertaken by the Environment Agency.

It is common for licences to specify that pumping groundwater should reduce or cease when water levels drop below specified limits, or when flow in rivers that depend on groundwater drops too low. However, if droughts get really intense, pumping groundwater may be our only option to maintain essential supplies.

Taking in the harvest during drought on the Chalk downland of the Berkshire Downs, Hampsted Norreys, August 2022. John Bloomfield BGS © UKRI.

How BGS is involved

BGS uses data collected during previous droughts to calibrate computer models of aquifers and combines the models with forecast weather data to estimate how groundwater will behave over the coming months. These groundwater predictions are further combined with colleagues’ predictions for river flow to produce a monthly Hydrological Outlook.

What is the current outlook for groundwater resources?

Our models allow us to be confident that levels in aquifers will remain low to notably low, and exceptionally low (defined as below the level expected once every 20 years) in only a few places for the next one-to-three months.

It is harder to predict how quickly groundwater levels in aquifers will recover beyond October 2022. We will need above average winter rainfall to recover levels back to where we started in early spring 2022 and another dry winter that fails to replenish aquifers back to normal levels could leave groundwater much more vulnerable to drought in 2023.

Groundwater and climate change

We can use similar modelling techniques to consider how aquifers might respond to climate change. Hotter summers, particularly over the Chalk, may result in increased rates of groundwater recession, while changes in the timing and length of the recharge season may also influence groundwater storage in the future. These are both areas of active BGS research. However, if hotter, drier summers do become more common, groundwater’s role as a safe storage reservoir to capture winter rainfall may become even more important in the future.

The current drought highlights not only how fortunate the UK is to have aquifers that can provide a degree of resilience for water supply, but also the importance of protecting groundwater quality and conserving this resource as a defence against serious shortages during longer droughts.

Relative topics

Latest blogs

AI and Earth observation: BGS visits the European Space Agency

02/07/2025

The newest artificial intelligence for earth science: how ESA and NASA are using AI to understand our planet.

Geology sans frontières

24/04/2025

Geology doesn’t stop at international borders, so BGS is working with neighbouring geological surveys and research institutes to solve common problems with the geology they share.

Celebrating 20 years of virtual reality innovation at BGS

08/04/2025

Twenty years after its installation, BGS Visualisation Systems lead Bruce Napier reflects on our cutting-edge virtual reality suite and looks forward to new possibilities.

Exploring Scotland’s hidden energy potential with geology and geophysics: fieldwork in the Cairngorms

31/03/2025

BUFI student Innes Campbell discusses his research on Scotland’s radiothermal granites and how a fieldtrip with BGS helped further explore the subject.

Could underground disposal of carbon dioxide help to reduce India’s emissions?

28/01/2025

BGS geologists have partnered with research institutes in India to explore the potential for carbon capture and storage, with an emphasis on storage.

Carbon and oxygen isotope analysis of carbonates and the development of new reference materials

18/12/2024

Dr Charlotte Hipkiss and Kotryna Savickaite explore the importance of standard analysis when testing carbon and oxygen samples.

Studying oxygen isotopes in sediments from Rutland Water Nature Reserve

20/11/2024

Chris Bengt visited Rutland Water as part of a project to determine human impact and environmental change in lake sediments.

Celebrating 25 years of technical excellence at the BGS Inorganic Geochemistry Facility

08/11/2024

The ISO/IEC 17025 accreditation is evidence of technical excellence and reliability, and a mark of quality assurance.

Electromagnetic geophysics in Japan: a conference experience

23/10/2024

Juliane Huebert took in the fascinating sights of Beppu, Japan, while at a geophysics conference that uses electromagnetic fields to look deep into the Earth and beyond.

Exploring the role of stable isotope geochemistry in nuclear forensics

09/10/2024

Paulina Baranowska introduces her PhD research investigating the use of oxygen isotopes as a nuclear forensic signature.

BGS collaborates with Icelandic colleagues to assess windfarm suitability

03/10/2024

Iceland’s offshore geology, geomorphology and climate present all the elements required for renewable energy resources.

Mining sand sustainably in The Gambia

17/09/2024

BGS geologists Tom Bide and Clive Mitchell travelled to The Gambia as part of our ongoing work aiming to reduce the impact of sand mining.