The geology of Tynemouth area is a mix of strong rocks and formations that are less resilient to constant attack from the sea. Various processes affect the stability of the Pen Bal Crag headland and the coastline of King Edward’s Bay, and a range of landslide types can be observed. Several defences have been constructed and these need maintenance and repair to preserve this rocky headland.

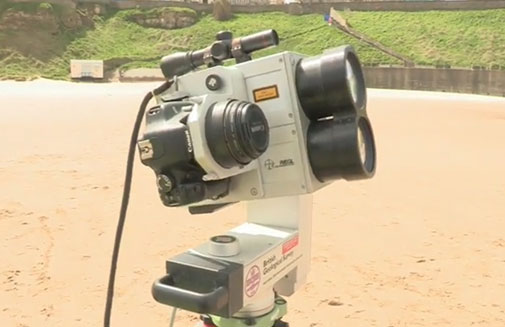

BGS used a LiDAR laser scanner to scan the cliffs and provide valuable assistance in assessing the instability processes that affect these sites.

Geologists Helen Reeves, Claire Dashwood and Pete Hobbs carrying out a laser scan survey of the north-facing cliffs of the Pen Bal Crag headland from Short Sands beach in King Edward’s Bay, Tynemouth (summer 2013). BGS © UKRI.

Geology

The geology at Tynemouth comprises mainly Permian and Carboniferous bedrock.

The Permian bedrock consists of the Raisby Formation dolostone and the Yellow Sands Formation sandstone. In turn, this overlies Carboniferous sandstone followed by a series of relatively weak mudstones, siltstones and sandstones of the Pennine Middle Coal Measures Formation.

Cutting through these bedrock materials is a microgabbro dyke (an intrusion of Igneous rock), probably formed during the Palaeogene. Thick Devensian glacial till deposits overlie these bedrock materials, with the exception of the Permian bedrock headland, which is free of till.

This area forms the southern part of a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) that stretches from Tynemouth to Seaton Sluice.

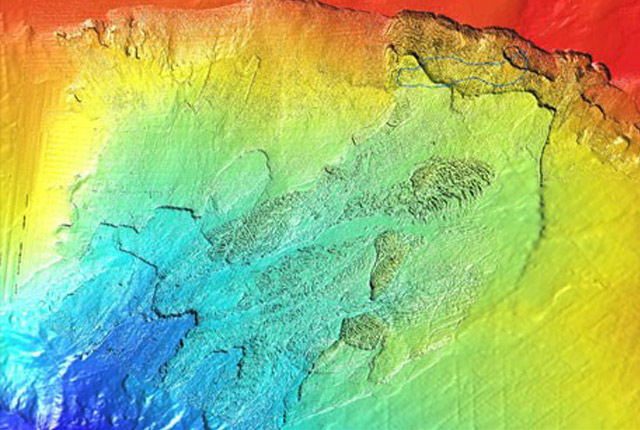

A coloured 3D point cloud, an output from the terrestrial laser scanning, of the north-facing cliffs of the Pen Bal Crag headland; taken from the Short Sands beach in King Edward’s Bay, Tynemouth. BGS © UKRI.

Tynemouth Castle headland: Pen Bal Crag and King Edward’s Bay

The geology of Tynemouth has had a profound effect on its history; a strong and resilient igneous microgabbro dyke provided a natural pier jutting out to sea and protecting the northern coastline of the Tyne estuary. Local dolostone and sandstone were sufficiently resistant to form a prominent rocky headland, known as Pen Bal Crag, to the north of the dyke.

This special location led to the foundation of a priory, early in the 7th century. In the subsequent centuries the early Northumbrian kings were buried here. However, a long period of ransacking and rebuilding ensued.

Late in the 13th century, the fortifications of the priory became more substantial and much of the remains can still be observed today.

Slope instability

Various processes affect the stability of the Pen Bal Crag headland and the coastline of King Edward’s Bay. A range of landslide types can be observed. Rockfalls mainly occur along the headland, while in the King Edward’s Bay landsliding is often complex and involves falls, slides and flows.

English Heritage looks after the site and has engaged in several phases of stabilising the cliffs, including maintenance of the concrete arches that were first constructed more than 100 years ago. A large cavity, measuring 4 m, was found behind the concrete arches requiring casting of a large concrete base, anchored into the bedrock.

The wet summer of 2012 resulted in an increased activity of landsliding across the nation and King Edward’s Bay also experienced increased activity during this period.

Landsliding at the bay involves local rock (fragments of dolostones and sandstones), but most of the slide material is dark grey in colour and probably involves fill material sliding over a stable bedrock surface.

The upper slopes, comprising Permian bedrock, have been stabilised using mesh and rock bolts.

Monitoring of unstable slopes

BGS has carried out LiDAR (laser scan surveys) of the headland and the bay. These scans provide valuable assistance in assessing the instability processes that affect these sites. Multiple scans, taken over a period of time, allow comparative analyses that help build up a picture of the coastal changes that are occurring.

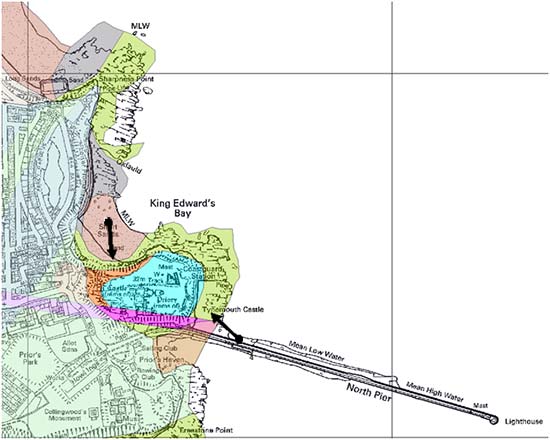

The locations from where the terrestrial laser scans were taken from on Short Sands beach in King Edward’s Bay and from the North Pier. BGS © UKRI. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown Copyright and database rights 2021.

Gallery

Complex landsliding affecting the morphology of the north-facing cliffs of the Pen Bal Crag headland from Short Sands beach in King Edward’s Bay, Tynemouth. BGS © UKRI.

Complex landsliding affecting the morphology of the north-facing cliffs of the Pen Bal Crag headland from Short Sands beach in King Edward’s Bay, Tynemouth. BGS © UKRI.

A coloured 3D point cloud from the scan draped over a landscape surface model of the south-facing cliffs of the Pen Bal Crag headland; taken from the North Pier, Tynemouth. BGS © UKRI.

Detail of the cliffs of the Pen Bal Crag headland clearly showing how joints and bedding planes of the local sandstone combine to create a vertical slope that is very susceptible to large rockfall. BGS © UKRI.

Tynemouth Castle and Priory ruins, 2013. Photo taken from North Pier looking north-north-west. Permian Upper and Lower Magnesian Limestone on Yellow Sands on Middle Coal Measures sandstone. BGS © UKRI.

You may also be interested in

Landslide case studies

The landslides team at the BGS has studied numerous landslides. This work informs our geological maps, memoirs and sheet explanations and provides data for our National Landslide Database, which underpins much of our research.

Understanding landslides

What is a landslide? Why do landslides happen? How to classify a landslide. Landslides in the UK and around the world.

How to classify a landslide

Landslides are classified by their type of movement. The four main types of movement are falls, topples, slides and flows.

Landslides in the UK and around the world

Landslides in the UK, around the world and under the sea.