Mam Tor is 2 km north-west of Castleton in the Peak District, Derbyshire, where it stands between the White Peak and Dark Peak.

Mam Tor, Derbyshire, location map. BGS © UKRI.

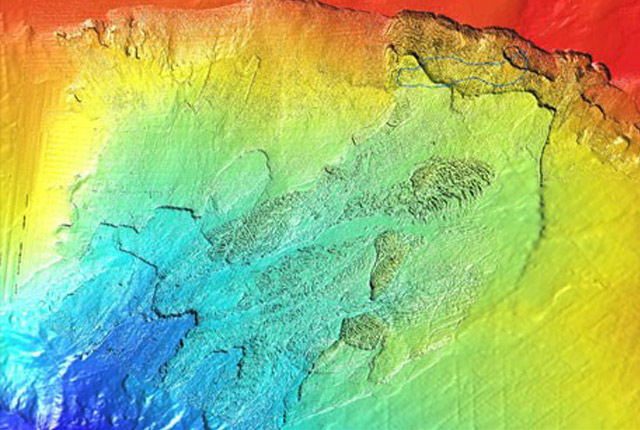

The summit of Mam Tor is ringed by the remains of the ditch and rampart of a once-great Iron Age hillfort, but it is also famous for its large landslide. The landslide is easy to access and exhibits classic, textbook landslide features so is a good landslide for geologists, geomorphologists, geographers and engineers to study. It is National Landslide Database ID 5481/1.

The Mam Tor landslide, showing the 70 m-high backscarp. BGS © UKRI.

A625 Manchester to Sheffield road

The Sheffield Turnpike Company first constructed the A625 Manchester to Sheffield road in 1819 using spoil from the nearby Odin mine (National Trust, 2009) and the road crosses the main body of the landslide twice as it winds its way up the slope. The following 160 years saw constant repairs and reconstruction. In 1977, the landslide moved again and the road was restricted to single-lane traffic (Cripps and Hird, 1992). In 1979, the road was permanently closed to traffic and what remains today is an interesting example of landslide movement and repeated road reconstruction and repair.

The landslide

The landslide itself is over 4000 years old and is a rotational landslide, which has developed into a large debris flow at its toe (Waltham and Dixon, 2000). It is over 1000 m from backscarp to toe, has a maximum thickness of 30–40 m and the backscarp is over 70 m high.

Mam Tor landslide. Photo taken from the debris flow looking towards the backscarp. BGS © UKRI.

Waltham and Dixon (2000) have divided the landslide into three distinct zones (backscarp area, transition zone and debris flow) according to their structure.

Backscarp area

The upper part of the slide material is a series of rock slices or blocks that were produced by the non-circular rotational failure of the original slope. Most of these slices above the upper road show little sign of current movement.

Transition zone

The central part of the slide is a transition zone, forming most of the ground between the two segments of road. It lies between the upper landslide blocks and the lower debris flow. It is composed of an unstable complex of blocks and slices, some of which can be identified by ground breaks along their margins. They overlie the steepest part of the landslide’s basal shear, which was the hillside immediately downslope of the initial failure. The upper road lies along the highest section of the transition zone, which is currently the most active part of the whole slide.

Debris flow

Disintegration of the lower part of the slipped material has created a debris flow that now forms half the total length of the slide. This is described as a flow because it moves as a plastic deformable mass, but it may also be regarded as a debris flow slide because it has a well-defined basal shear surface.

The literature listed below give good accounts of this landslide in more detail.

The geology

Underlying the landslide are Dinantian limestones which are not included with the landslide (Waltham and Dixon, 2000). Overlying the limestone is the Bowland Shale Formation which consist of dark grey mudstone. The top of the landslide exposes the Mam Tor Beds. These are a sequence of turbidites of mudstones siltstones and sandstones.

Further reading

Aitkenhead, N, Barclay, W J, Brandon, A, Chadwick, R A, Chisolm, J I, Cooper, A H, and Johnson, E W. 2002. British Regional Geology: the Pennines and Adjacent Areas. Fourth Edition. (Nottingham, UK: British Geological Survey.)

Arkwright, J C, Rutter, E H, and Holloway, R F. 2003. The Mam Tor landslip: still moving after all these years. Geology Today, Vol. 19, 59–64.

Cripps, J C, and Hird, C C. 1992. A guide to the landslide at Mam Tor. Geoscientist, Vol.2(3), 22–27.

Dixon, N, and Brook, E. 2007. Impact of predicted climate change on landslide reactivation: case study of Mam Tor, UK. Landslides, Vol. 4(2), 137–147.

Donnelly, L J. 2006. The Mam Tor Landslide, Geology & Mining Legacy around Castleton, Peak District National Park, Derbyshire, UK. In Engineering Geology for Tomorrow’s Cities. Culshaw, M G, Reeves, H, Jefferson, I, and Spink, T (editors). Proceedings of the 10th Congress of The International Association for Engineering Geology and The Environment, Nottingham, UK, 6–10 September 2006. Geological Society London (CD-ROM).

Doornkamp, J C. 1990. Landslides in Derbyshire. East Midland Geographer, Vol. 13, 33–62.

Rutter, E H, Arkwright, J C, Holloway, R F, and Waghorn, D. 2003. Strains and displacements in the Mam Tor landslip, Derbyshire, England. Journal of the Geological Society of London, Vol. 160(5), 735–744.

Skempton, A W, Leadbeaater, A D, and Chandler, R J. 1989. The Mam Tor landslide, north Derbyshire. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Vol. 329, No. 1607, 503–547.

Walstra, J, Dixon, N, and Chandler, J H. 2007. Historical aerial photographs for landslide assessment: two case histories. Quarterly Journal of Engineering Geology and Hydrogeology, Vol. 40(4), 315–332.

Waltham, T, and Dixon, N. 2000. Movement of the Mam Tor landslide, Derbyshire, UK. Quarterly Journal of Engineering Geology and Hydrogeology, Vol. 33(2), 105–123.

You may also be interested in

Landslide case studies

The landslides team at the BGS has studied numerous landslides. This work informs our geological maps, memoirs and sheet explanations and provides data for our National Landslide Database, which underpins much of our research.

Understanding landslides

What is a landslide? Why do landslides happen? How to classify a landslide. Landslides in the UK and around the world.

How to classify a landslide

Landslides are classified by their type of movement. The four main types of movement are falls, topples, slides and flows.

Landslides in the UK and around the world

Landslides in the UK, around the world and under the sea.