Will 2024 be the Year of the Aurora?

The Sun’s approximate eleven-year activity cycle is predicted to peak this year, prompting BGS scientists to anticipate that 2024 will be the ‘Year of the Aurora’.

23/02/2024

The aurora is a natural display of light in the night sky, with bands of green, red or purple lights that shimmer and change appearance over time. It is usually seen around the Arctic and Antarctic circles, which are also referred to as ‘auroral zones’.

The northern lights (or aurora borealis) can often be seen in Alaska, Canada, Iceland, Scandinavia, Finland and Russia, whilst the southern lights, or aurora australis, can be observed in Antarctica, New Zealand and Australia. However, during periods of intense geomagnetic activity, the auroral zones broaden and travel toward the equator. At these times people who live at lower latitudes, such as in the UK, may have a better chance of seeing the aurora too.

Strong solar activity can affect the Earth’s magnetic field and result in spectacular displays of the northern and southern lights. As solar activity is expected to peak in 2024, we could be in for some beautiful skies this year.

Why does the aurora happen?

The aurora we see dancing in the night sky is caused by activity on the Sun. The Sun is an enormous ball of super-hot ionised gas that continually emits a stream of charged particles, which is known as the solar wind. The solar wind isn’t always the same; its speed and strength can vary depending on solar activity driven by a variety of structures, such as coronal holes and active regions, that can be observed on the surface of the Sun.

Coronal holes are temporary features that can form on the Sun. These are vast areas where the Sun’s magnetic field opens up, allowing the high-speed solar wind to stream out into the solar system. This fast solar wind can take around three days to reach us on Earth.

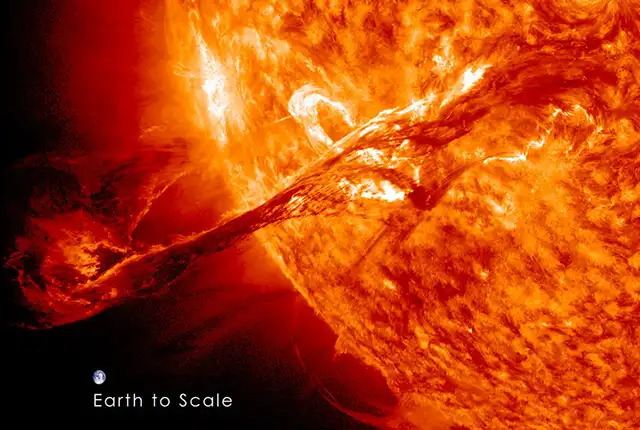

A coronal mass ejection erupting into space on 31 August 2012. An image of Earth is superimposed to show the size of the coronal mass ejection compared to the size of the Earth. © NASA/GSFC/SDO.

Active regions on the Sun are areas of strong and complex magnetic fields. These areas appear as dark ‘sunspots’ on the solar surface and can produce explosive events such as solar flares and coronal mass ejections. Coronal mass ejections are huge fast-moving clouds of charged particles launched by the Sun. They may take one to three days to arrive at Earth.

If these solar ‘storms’ are directed towards the Earth, the solar wind will interact with the Earth’s magnetic field, which directs the solar wind’s particles toward the polar regions. These charged particles slam into the atoms in the Earth’s atmosphere and the energy released during these collisions is emitted as light, causing the glow of the aurora.

The colours that appear depend on the mixture of gases in the atmosphere. Green aurorae result from interactions of solar particles with oxygen; however, at higher altitudes, collisions with oxygen produce red aurorae. Blue and purple shades are caused by collisions with nitrogen.

What is the solar cycle?

The Sun goes through an approximate eleven-year activity cycle, which is measured by the number of sunspots seen on the Sun. During solar minimum, few sunspots are counted and solar activity is usually low. During solar maximum, many sunspots are seen, increasing the frequency of solar storms. As we know, these solar storms can lead to geomagnetic disturbances on Earth.

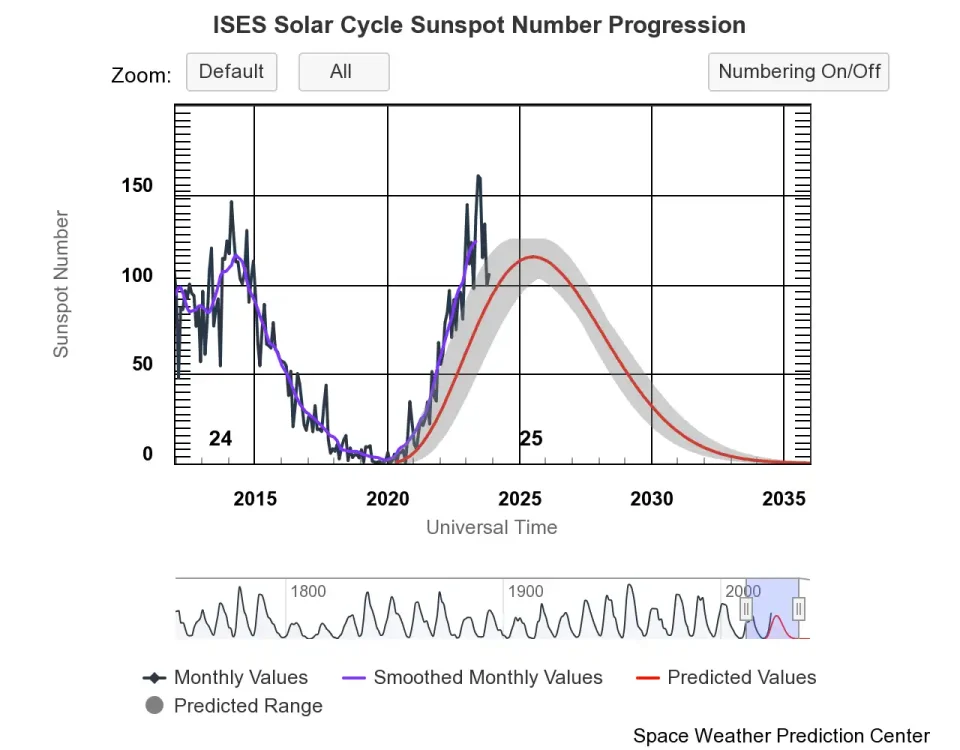

Solar cycles have been recorded since the eighteenth century. Back in 2020, a panel of scientists predicted that the current solar cycle (solar cycle 25) would be fairly weak, similar to the previous cycle. Solar activity was expected to peak around July 2025. In October 2023, the Space Weather Prediction Center of the USA’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration issued a revised prediction for solar activity. This forecast a quicker, stronger peak of activity with solar maximum expected between January and October 2024.

This is why we expect 2024 to be a good year for aurora-spotting opportunities.

A plot of sunspot numbers from 2012 showing the end of solar cycle 24, the start of solar cycle 25 from 2020 and the original prediction (in red). Actual solar activity has risen faster and higher than predicted. From https://www.swpc.noaa.gov/products/solar-cycle-progression.

Why is BGS interested in the aurora?

Knowledge of the Earth’s geomagnetic field is necessary when using a compass to navigate. The location of Earth’s magnetic poles gradually shifts over time and scientists at BGS model these movements to predict how it will change in the future.

Strong and rapid variations in the Earth’s magnetic field due to solar storms can cause errors in the magnetic corrections required for navigation and induce electric currents in the ground, which can then travel into power lines, pipelines and railways. In the power grid, these geomagnetically induced currents can overload transformers, resulting in power outages. They can increase corrosion in pipelines and can disrupt railway signalling (as recently reported by BBC News).

BGS provides various space weather services to organisations such as the National Grid, the UK Met Office and the European Space Agency to monitor current geomagnetic conditions and forecast future geomagnetic activity.

How can I see the northern lights in the UK?

The likelihood of seeing the northern lights varies across the UK and depends on a number of factors, most importantly how disturbed the Earth’s magnetic field is and how far north you are. Those in the north of Scotland may see the northern lights often with only minor geomagnetic disturbances. When activity gets more disturbed and the auroral zone moves southward, more of Scotland, Northern Ireland and the north of England have a chance of seeing it. It usually requires a rare and significantly large magnetic storm for the aurora to be seen widely across southern England and Wales.

The aurora sits above cloud level, so you need to get lucky with the UK’s typically overcast weather as clear skies are necessary to spot the aurora. Head to a dark place away from light pollution; a full moon can also cause issues if the aurora is faint. Generally, look to the north, although during intense storms it could be overhead or elsewhere. Having a clear view to the northern horizon either from the coast or from an elevated position can be advantageous.

Aurora borealis photographed from the Vale of Belvoir, Nottinghamshire, November 2023. © Jacqueline Hannaford.

Expectation vs reality

To get the best view of the aurora you will need a camera. Photographs of the aurora will often portray the aurora as much brighter than can be seen by the naked eye. Long-exposure photographs can take in more light, exposing the colours in the sky, whilst by eye a weak aurora may appear more monochrome and cloud-like. This YouTube video explains more.

Modern smartphones often have night-mode photography options, which can take reasonable photos of the aurora without the need for expensive photographic equipment. Having a tripod to stabilise your camera or smartphone can help avoid vibration during long-exposure photographs.

Stay updated with the BGS

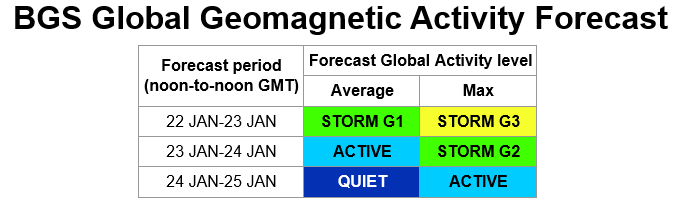

- BGS produces daily three-day forecasts of geomagnetic activity

- We also post daily 24-hour forecasts on X (formerly Twitter)

- When there is significant geomagnetic storm predicted, we send out notifications to inform the public of the increased chance of seeing the aurora: sign up for these email alerts or you can follow the alerts on X

An example of the BGS geomagnetic activity forecast for a three-day period. We predict the average and maximum global geomagnetic activity. BGS © UKRI.

About the author

Sarah Reay

Geomagnetic data analyst

Relative topics

Related news

Funding awarded to UK/Canadian critical mineral research projects

08/07/2025

BGS is part of a groundbreaking science partnership aiming to improve critical minerals mining and supply chains.

AI and Earth observation: BGS visits the European Space Agency

02/07/2025

The newest artificial intelligence for earth science: how ESA and NASA are using AI to understand our planet.

Release of over 500 Scottish abandoned-mine plans

24/06/2025

The historical plans cover non-coal mines that were abandoned pre-1980 and are available through BGS’s plans viewer.

New collaboration aims to improve availability of real-time hazard impact data

19/06/2025

BGS has signed a memorandum of understanding with FloodTags to collaborate on the use of large language models to improve real-time monitoring of geological hazards and their impacts.

Modern pesticides found in UK rivers could pose risk to aquatic life

17/06/2025

New research shows that modern pesticides used in agriculture and veterinary medicines have been found for the first time in English rivers.

Goldilocks zones: ‘geological super regions’ set to drive annual £40 billion investment in jobs and economic growth

10/06/2025

Eight UK regions identified as ‘just right’ in terms of geological conditions to drive the country’s net zero energy ambitions.

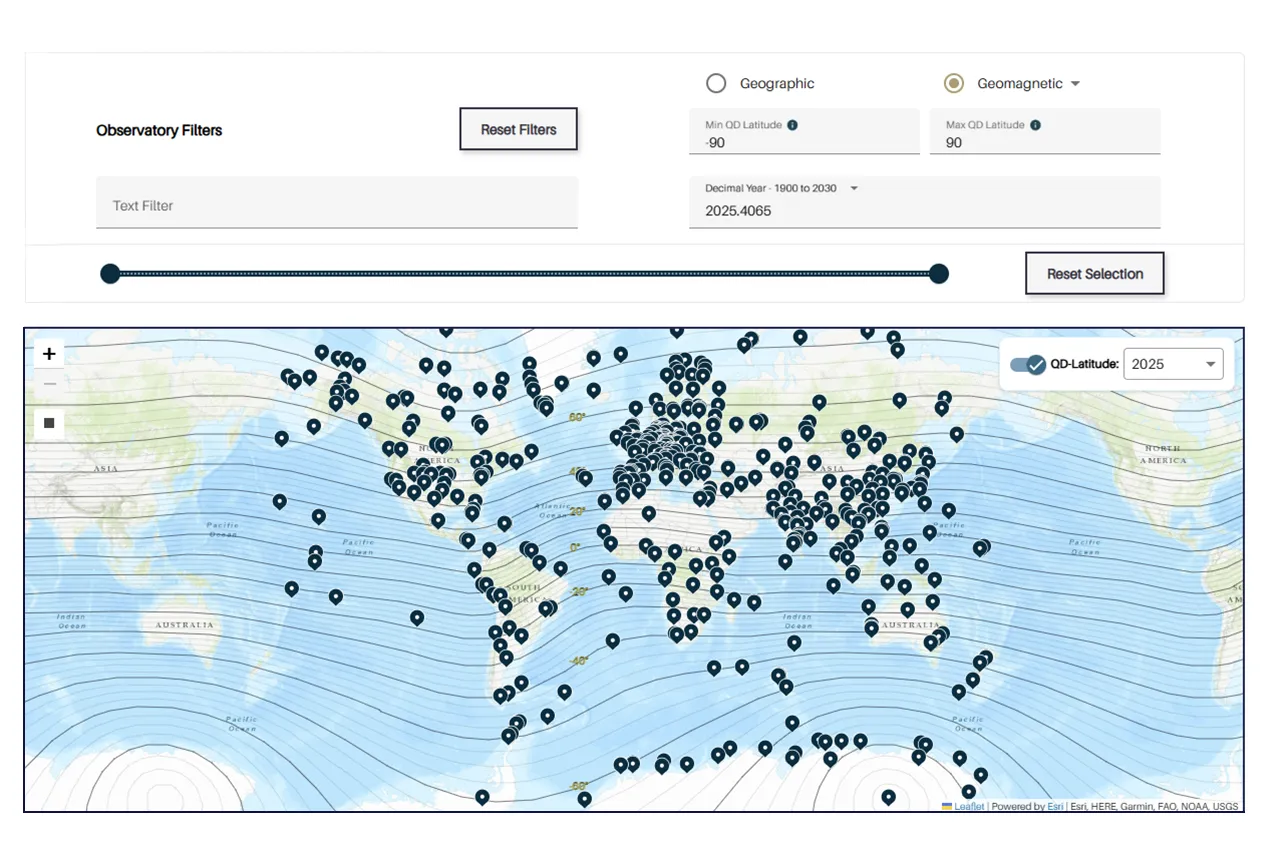

Upgraded web portal improves access to geomagnetism data

02/06/2025

BGS’s geomagnetism portal, which holds data for over 570 observatories across the world, has received a significant update.

BGS digital geology maps: we want your feedback

29/05/2025

BGS is asking for user feedback on its digital geological map datasets to improve data content and delivery.

What is the impact of drought on temperate soils?

22/05/2025

A new BGS review pulls together key information on the impact of drought on temperate soils and the further research needed to fully understand it.

UK Minerals Yearbook 2024 released

21/05/2025

The annual publication provides essential information about the production, consumption and trade of UK minerals up to 2024.

BGS scientists join international expedition off the coast of New England

20/05/2025

Latest IODP research project investigates freshened water under the ocean floor.

New interactive map viewer reveals growing capacity and rare earth element content of UK wind farms

16/05/2025

BGS’s new tool highlights the development of wind energy installations over time, along with their magnet and rare earth content.