Boreholes aren’t boring!

Work experience student Patrick visited BGS to learn more about being a professional rock lover.

31/07/2023 By BGS Press

First and foremost, I’m Patrick and studying chemistry, geography and maths at A Level. For a week in July 2023, I was on work experience at BGS. I’ve had a passion for geology since I was brought to the Keyworth site for BGS open days, and I’m now intending to pursue a career in the subject.

The theme for week followed the journey of a borehole through BGS, which led to engaging with many areas and activities, including:

- a tour of the National Geological Repository (aka the Core Store)

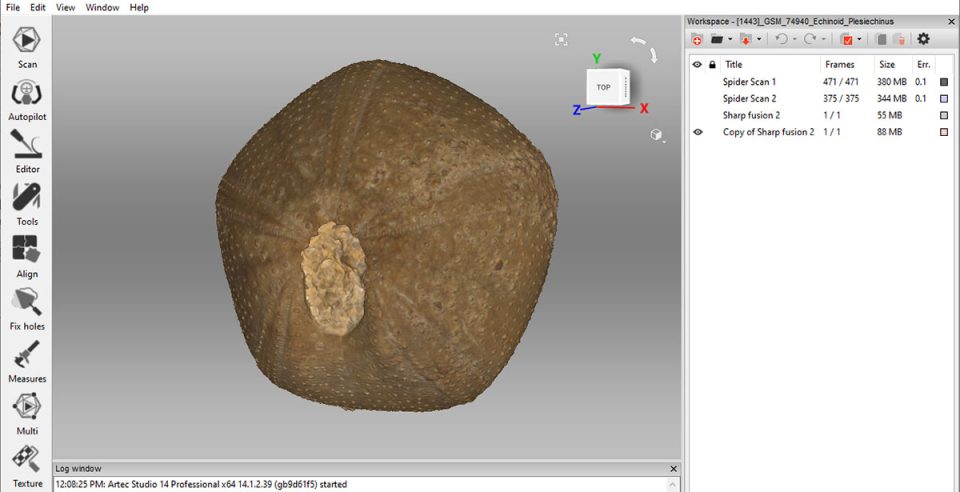

- an introduction to 3D scanning of fossils with Simon Harris, the collections conservation and digitisation manager

- digital borehole logging and some 3D modelling with Steve Thorpe, a geospatial data specialist

- meetings with members of communications team — Lee, Penny, Jade and Michael

- chatting with PhD student Ellis Hammond about his research on new digital tools to help speed up the redevelopment of brownfield land

- an introduction to the Core Scanning Facility and digital borehole data with petrophysicist Mark Fellgett

The borehole journey through BGS starts with sinking a borehole into the ground using specialised rock coring equipment. Borehole depths can range from 5 to 5000 m into the ground, each one providing unique insights into the world beneath our feet. A special drill bit is used to collect a core of the rock, which is then extracted, packaged up and transported back to the National Geological Repository at BGS Keyworth, where it’s registered.

The rock core is logged during a visual inspection of the different rock layers present in the sample. Many of the borehole logs and cores at BGS are from before the age of computers, handwritten on paper from as early as the mid-1800s. These older, handwritten logs are currently being converted into digital logs, with further scans being taken of the paper copies. They can then be input into software to build 3D models of the subsurface or used to create large-scale maps of the geology below our feet.

The core is then scanned, photographed and tested to gather data on its properties. For example, gamma rays can be used to test the density of a rock, P-waves can be used to measure the porosity, and X-rays, infrared spectroscopy and some chemical tests develop a picture of the rock’s properties.

An echinoid (sea urchin) fossil that Simon and I scanned. BGS © UKRI.

Borehole data is being used to inform the transition to net zero. BGS researches the properties of rocks and the subsurface environment to work out if they can be used to store large quantities of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from industry and power generation. This area of applied research is called carbon capture and storage (CCS) and the technology is a means of reducing the amount of CO2 that is released into the atmosphere.

CCS is the process of injecting CO2 under high pressure (so it is more like a liquid than a gas) into porous sedimentary rocks in areas such as old oil or gas fields, which are then filled with salty water. Boreholes are key in deciding which areas are suitable for CCS, as they allow scientists to work out which rocks can store CO2, how much CO2 they can hold and whether it is likely to escape in the future.

Boreholes are also used to access geothermal energy present underground, for example using the water from abandoned mines. This water can store plenty of heat, depending on a range of factors. The water is pumped up to the surface where the heat can be extracted and used to provide a sustainable heat source. This reduces the need for CO2-producing fossil-fuel power plants.

All in all, my week at BGS has been valuable in demonstrating the fascinating research that occurs here, and the broad range of skills that people need to conduct it. It has given me plenty of motivation to aim for a career in geology. nassive thank you to Dr Darren Beriro for organising my visit and to Steve Thorpe and Mark Fellgett for looking after me on a day-to-day basis.