In the centre of Stoke Row, high in the Chiltern Hills, is an incongruous sight; a highly ornate wrought iron pavilion that shelters a windlass, capped with a sculpture of a golden elephant, placed over a water well. The story of the Maharaja’s Well is not just cultural but is intimately bound up with the geology of the Chilterns.

Windlass for raising water on top of the Maharaja’s Well. Source: BGS © UKRI

Origin of the well

In the 1860s, as a gesture of friendship to Edward Reade of the East India Company, the Maharaja of Benares (Varanasi) in India funded the digging of a well to improve Stoke Row’s water supply. Digging of the well started in 1863 and construction took a year. The well cost £353, equivalent to £45 000 at today’s prices.

The pavilion that shelters the Maharaja’s Well. BGS © UKRI.

So why was such an expensive well needed by the village?

Before the availability of piped water, the only practical sources of water would have been ponds, streams or rivers, shallow wells and collecting rainwater.

Geology of the area

The Chiltern Hills are formed by an outcrop of the Chalk Group, a fine white limestone that was deposited in the Cretaceous. A key feature of chalk is that it is very porous. Rainwater that falls on the hills quickly soaks into the rock, so there are very few ponds, streams, or rivers. The only place where ponds form up on the hills is where you find caps of the Lambeth Group or clay-with-flints (thin deposits of clay and sands that are the remnants of thick, marine deposits that would have overlain the chalk but have been largely eroded away). The clay in these deposits, in contrast to the chalk, is impermeable so that rainwater doesn’t soak in. Instead, it runs off the surface and can collect in ponds. At the edge of these clay deposits the water will soak into the chalk, which acts like a giant sponge (an aquifer) from which you can extract water with wells.

Demand for water

Stoke Row, in common with many other Chiltern villages, was built on the edge of one of these caps of clay-with-flints, not only because there was access to water, but because the clay could be dug out and used for construction. But the clay deposits don’t soak up water so, during dry spells, the ponds will dry up and water becomes scarce. As the village’s population grew, demand for water will have begun to exceed the supply available from ponds and, with better understanding of how important clean water is for health, drinking polluted pond water was increasingly unacceptable.

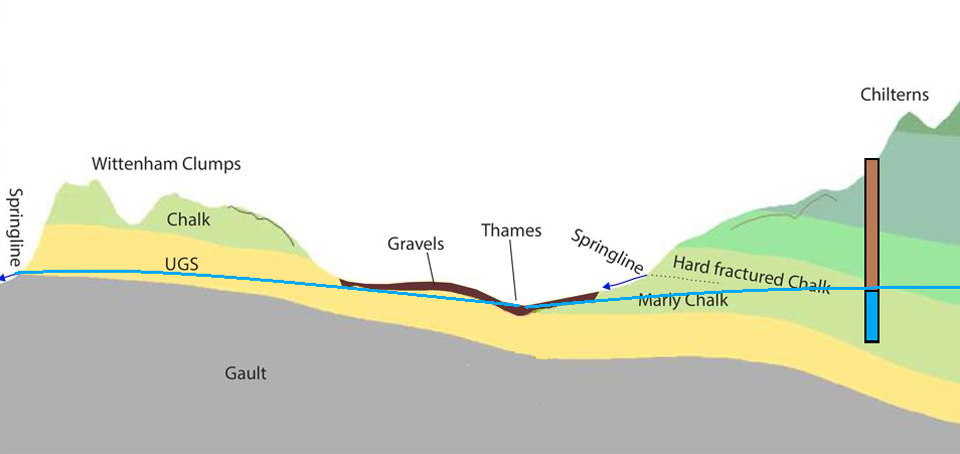

In the 1800s, with developing understanding of geology and the behaviour of the water table, more Chiltern communities started to dig deep wells. The free-draining chalk means the water table never gets much above the level in the few local rivers. For Stoke Row, this means that the water table is nearly 100 m below ground — almost exactly at the level of the River Thames, which flows through the Chilterns 10 km south of the village. This means that the well needed to be dug 112 m to access a secure supply of water; this was both difficult and expensive.

Cross-section illustrating how the well is dug down through the Chalk Group to the water table, which is at the level of the River Thames. BGS © UKRI.

Visiting the well

As you stand in front of the canopy, it’s hard to envisage how deep the well is — almost as deep as a standard football pitch is long. A display board shows you the geological structure below the well. You won’t find outcrops of chalk close to the well, but walk east a few metres along the road from the well and you can stroll around a field called the ‘Ishree Bagh’, which was planted with cherry trees by the Maharaja to provide an income to maintain the well, which is constructed on the old clay pits dug in the clay-with-flints. The ‘ravine’, which is actually an excavation in the centre of this field, is dug through the deposit and is dry because the water is soaking into the chalk. Shallower excavations at the far end of the field retain water.

To visit the well, park at the village hall in Stoke Row.

More information

- More information on Maharaja’s Well

- More information on the geology of the Chilterns

About the author

McKenzie Andrew

Groundwater information manager

Relative topics

You may also be interested in

Discovering Geology

Discovering Geology introduces a range of geoscience topics to school-age students and learners of all ages.

Maps and resources

Download and print free educational resources.

Postcard geology

Find out more about sites of geological interest around the UK, as described by BGS staff.