The north-west Highlands of Scotland have a unique scenery. Rolling knolls of rock stand out on low-lying, boggy land, which is interspersed with isolated, forbidding mountains like Suilven, Ben Stack and Quinag. Lochans, waterfalls, tiny crofting communities and the occasional castle dot the landscape. The whole area was gouged by glaciers during the last ice age, leaving this starkly beautiful landscape behind.

The isolated peaks of (left to right) Canisp, Suilven and Cùl Mòr in the north-west Highlands of Scotland. © Jacqueline Hannaford.

Evidence of the great forces and endless time that have shaped this landscape is all around you here. Road cuttings at Laxford Bridge show dykes and veins of different rocks cross-cutting each other in breathtaking three-dimensional views. Across Loch Glencoul near Kylesku is a stunning view of a fault called the Glencoul Thrust, clearly showing vastly ancient Lewisian gneiss somehow sitting atop younger Cambrian quartzite. Erratic boulders, dropped by retreating glaciers at the end of the ice age, speak of thousands of tonnes of ice inexorably grinding out the steep slopes and deep valleys. It feels like everywhere you look, the geology speaks to you of the astonishing forces that have been at play here in the unimaginably distant — and not so distant — past.

The Moine Thrust

Thrust faults are low-angle faults where the ‘hanging wall’ (the rocks above the fault plane) moves up relative to the ‘footwall’ (the rocks below the fault plane). They are indicative of compression, where rocks have been squeezed and eventually fractured by tectonic forces, sliding the hanging wall rocks up and over the footwall rocks.

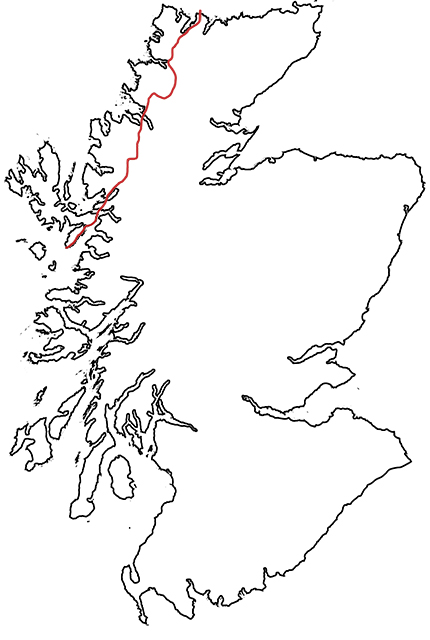

Location of the Moine Thrust from Loch Eriboll in the north to the Isle of Skye in the south. BGS © UKRI.

The Moine Thrust Belt is a fault zone that cuts across the north-west corner of Scotland, from Loch Eriboll in the north to the Sleat peninsula on the Isle of Skye in the south. Like most major faults, the fault zone comprises several faults branching off each other in a complex arrangement that accommodated different phases of compression over a long period of time: the Sole Thrust, the Glencoul Thrust and the Moine Thrust itself are all part of the fault zone. The Moine Thrust marks the eastern edge of the Moine Thrust Belt.

Loch Glencoul and the Glencoul Thrust. The thick, pale band is Cambrian quartzite that is up to 540 million years old; overlying it is the Lewisian gneiss, over 2 billion years older than the quartzite. The Glencoul Thrust fault separates the two rock units. © Jacqueline Hannaford.

This fault was active during the Caledonian orogeny, a period of mountain building that happened over about 100 million years, from the Ordovician Period to the Early Devonian. In this area, the main movements occurred between 440 and 410 million years ago, during the Silurian Period. Before this time, Scotland (Caledonia in Latin) was physically separated from the rest of the UK by an ocean called the Iapetus Ocean. Instead, it was part of a continent called Laurentia, alongside parts of North America; fossils found in this part of Scotland are identical to those found in North America and different to those from England and Wales.

As tectonic forces closed the ocean, compression forced older rocks in the east up and over the younger rocks in the west. The rocks folded and fractured in response to the compression, creating a complex geology of thrust structures called a duplex that generations of geology students have visited to learn the art of geological mapping.

Knockan Crag National Nature Reserve

At Knockan Crag National Nature Reserve, between Ullapool and Inchnadamph, visitors can take a short, steep walk up to the plane of the Moine Thrust (which elsewhere lurks on rather more inaccessible mountainsides). Just above the car park is the Rock Room, an exhibition about the importance of this part of the world to the history of geology.

It was in this area that Geological Survey geologists Ben Peach and John Horne made their studies that resolved the ‘Highlands controversy’ of the 19th century. This was an argument between geologists about the rocks of the area, where the older (2.8 billion years old) Lewisian gneiss seemed to lie above the younger (500 million years old) Cambrian quartzite and limestone, which seemed impossible to 19th century geologists. The work of Peach and Horne, and other geologists such as Charles Lapworth, proved that huge movements of the crust had pushed the older rocks on top of the younger ones. A monument to Peach and Horne stands overlooking Loch Assynt near Inchnadamph to mark their dedication.

Monument to Peach and Horne at Inchnadamph. The inscription says: ‘To Ben N Peach and John Horne who played the foremost part in unravelling the geological structures of the north west Highlands 1883-1897. An international tribute erected 1930.’ © W L Tarbert, public domain.

The walk up to Knockan Crag is steep but short, and rewarded with beautiful views of Cùl Mòr and Cùl Beag over to the west and, for the excitable geologist, a close-up encounter with the famous fault itself. The trail is also dotted with artworks inspired by the geology and landscape of the area.

The Moine Thrust fault plane, with grey, 1000-million-year-old mylonitic psammite rocks on top of 500-million-year-old yellowish limestone. © Jacqueline Hannaford.

The author for scale alongside the Moine Thrust. © Jacqueline Hannaford.

The North-west Highlands Geopark

This entire area is so significant to geology that, in 2004, it was designated as the North-west Highlands Geopark, Scotland’s first UNESCO Geopark. It begins at Ullapool and the Summer Isles in the south and stretches north, bounded by the sea to the west and north and by the Moine Thrust Belt to the east, covering over 2000 km2 of mountains, hidden glens and the most stunning, white sand beaches this side of a postcard from the Caribbean. There are trails to follow, the Rock Stop visitor centre, local guides and self-driving tour routes, amongst much more, to help you explore this beautiful and fascinating corner of the country.

Ceannabeinne beach on the north Sutherland coast. © Jacqueline Hannaford.

More information

- Knockan Crag National Nature Reserve

- North-west Highlands Geopark

- Local walks from walkhighlands:

About the author

Lina Hannaford

Relative topics

You may also be interested in

Discovering Geology

Discovering Geology introduces a range of geoscience topics to school-age students and learners of all ages.

Maps and resources

Download and print free educational resources.

Postcard geology

Find out more about sites of geological interest around the UK, as described by BGS staff.