The River Trent is a highly active river that has carved and shaped the regional landscape of Nottinghamshire for thousands of years. In numerous places, it gently cuts its banks and provides fresh outcrops of rock, which can be seen in the village of Radcliffe on Trent.

Cliff walk

This small village has some lovely scenery, including a cliff walk that runs alongside the river. It offers great views north towards the city of Nottingham and is worth a visit for these alone.

Small cliff of Mercia Mudstone by the weir at Radcliffe on Trent, Nottinghamshire. © Oliver Wakefield, BGS/UKRI.

There are a couple of paths that branch off from the cliff walk which lead to a weir in the river. These paths, though functional, are not as well maintained or sturdy as the main cliff path. Please make sure you assess the conditions before venturing on these paths, good footwear combined with caution will never go out of fashion here.

It’s obvious when you’re getting close to your destination due to the white noise of the river gushing over the weir. Almost exactly adjacent to the weir, in one of the river banks, you can see a relatively good example of the local sedimentary rocks called the Mercia Mudstone Group.

What the rocks tell us

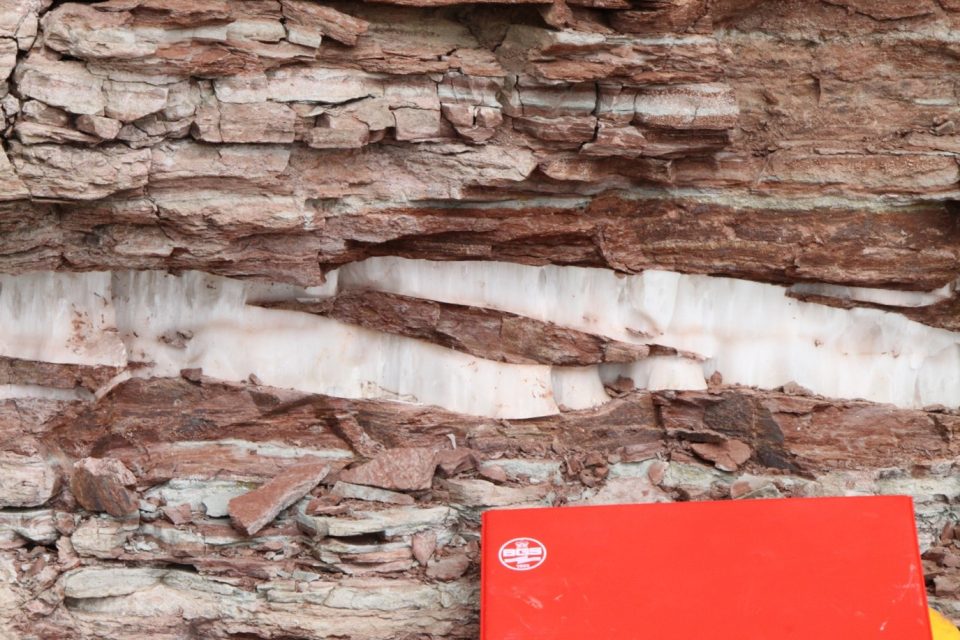

Firstly, you’ll see that the rocks have a variety of colours: pinky-reds, grey-greens, yellow-reds and even bright white. These colours are often arranged in horizontal layers. The rock itself is comprised of a mixture of mudstones and siltstones (mainly pinky-red and grey-green), very fine-grained sandstones (mostly yellow-red) and gypsum (white).

Whilst the small cliff looks like it is made of lots of horizontal layers, there are several more subtle features to find, including some ancient ‘fossilised’ ripples. These are most easily seen in the bits of rocks that have fallen onto the ground and look exactly like any sand ripple you’ve ever seen at the beach, but made of rock.

Fossilised sand ripples at Radcliffe on Trent. One pence piece for scale. © Oliver Wakefield, BGS/UKRI.

The character and composition of these layers allow us to work out information about how they were deposited and formed. The rocks in the river bank were originally deposited in a generally hot and arid landscape that had occasional or ‘ephemeral’ small lakes and ponds, likely caused by rainfall, that formed and dried up again repeatedly. The environment may have looked very similar to parts of modern central Australia.

Mineralisation — gypsum and halite

The gypsum bands are very interesting and are somewhat separate from the rest of the story of the other sediments. Gypsum is the mineral name for hydrated calcium sulphate, a type of salt, and it is both formed from and dissolved by water. If you look closely, you can see the gypsum layers may look horizontal, but they bend upwards or downcut into adjacent layers in places. This relationship tells us that the gypsum must have occurred after the other (mudstone, sandstone and siltstone) layers were deposited.

Gypsum band in the cliffs at Radcliffe on Trent. © Oliver Wakefield, BGS/UKRI.

The gypsum actually grew within the layers some (unknown) time after the other sediments were deposited, likely after the original sediments formed into rock. The gypsum isn’t the only evidence of a salt at the outcrop; some strange, small coin-sized ‘cubes’ can be seen on some layers. Again they are best seen on blocks that have fallen from the outcrop. These cubes are often referred to as ‘hoppers’ and formed due to the presence of another type of salt called halite, which is the very same salt you have on your dinner table — sodium chloride.

Unfortunately, the halite is long gone, but the evidence of its presence remains. The halite, which has a wonderful cubic mineral shape, formed just underground in this dry environment. It was then likely dissolved away by percolating water, leaving behind hundreds of small, cube-shaped hollows. Over time, as the layers compacted, the surrounding muds, silts and sands would have been squashed into these hollows, using them like blacksmith would use a mould for casting molten metal. The result is that the sediments took on the shape of the now-vanished halite crystals.

Halite hoppers in a chunk of Mercia Mudstone. © Oliver Wakefield, BGS/UKRI.

The technical name for these features is ‘pseudomorphs of mudstone/siltstone/sandstone after halite’. See if you can find some of these features, though please don’t pull away anything from the rock outcrop or use a geological hammer on the cliffs. There are always plenty of fallen blocks on the ground and these are fair game!

Be careful!

The rocks here are naturally a little weak and you should be cautious not to stand under any overhangs in the small 2 to 3 m-high cliff, as rocks do fall occasionally. Even from a distance much can be seen of the rocks in the river-bank cliff. Please also be aware there are risks associated with the river, please stay well back from the river edge and do not enter the water. Be mindful of weather conditions and deteriorating paths, especially branches off from the main cliff walk. River banks are constantly evolving landscapes and some of the routes may have changed since the time of writing.

About the author

Dr Oliver Wakefield

BGS Regional Geologist, Midlands and East Anglia

Relative topics

You may also be interested in

Discovering Geology

Discovering Geology introduces a range of geoscience topics to school-age students and learners of all ages.

Maps and resources

Download and print free educational resources.

Postcard geology

Find out more about sites of geological interest around the UK, as described by BGS staff.