Ostracods (formally called Ostracoda) take their name from the Greek ‘ostrakon’, which means ‘a shell’, and refers to the bi-valved carapace that is characteristic of these tiny crustaceans, which resemble water fleas. They had probably evolved by the end of the Cambrian and true fossil ostracods are found in Ordovician rocks. Ostracods are found commonly as fossils and are still living today in all aquatic habitats, from the deep sea to small temporary ponds. A few species can be found crawling around on land in moist habitats, such as wetland mosses.

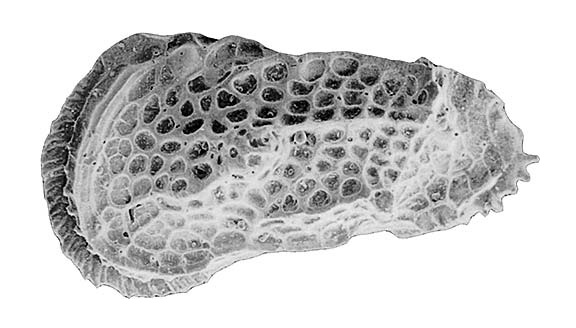

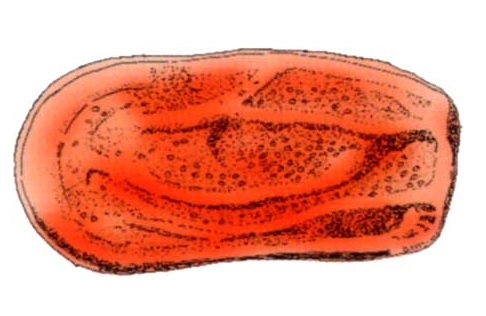

A podocopid ostracod from the mid-Cretaceous, Isocythereis fissicostis fissicostis Triebel, 1940. I P Wilkinson, BGS © UKRI.

The animal

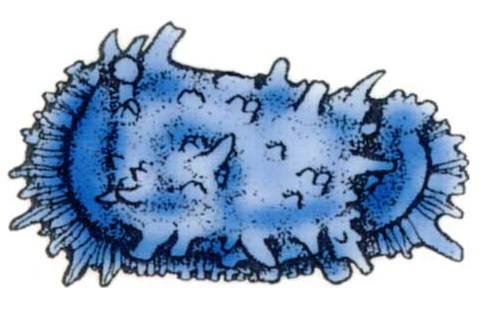

Ostracods are small animals belonging to the phylum Crustacea. Most are between 0.5 and 1.5 mm long, but a few (e.g. Gigantocypris, pictured) grow to about 25 mm.

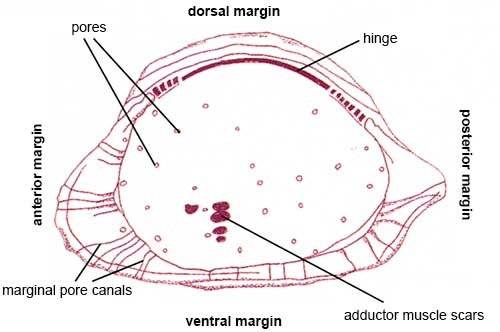

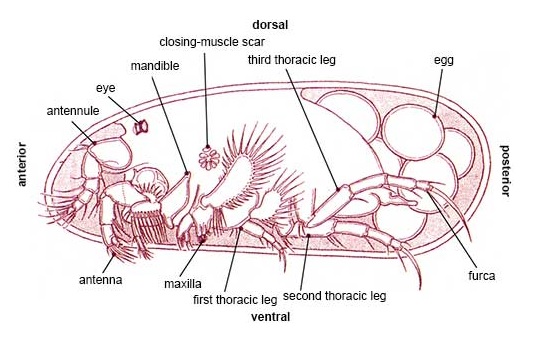

Ostracods have a bi-valved, calcareous carapace (shell) in which the animal is suspended. The body is attached laterally to the carapace by muscles, the scars of which can often be seen on the inner surface of the valve. The valves are hinged along the dorsal margin.

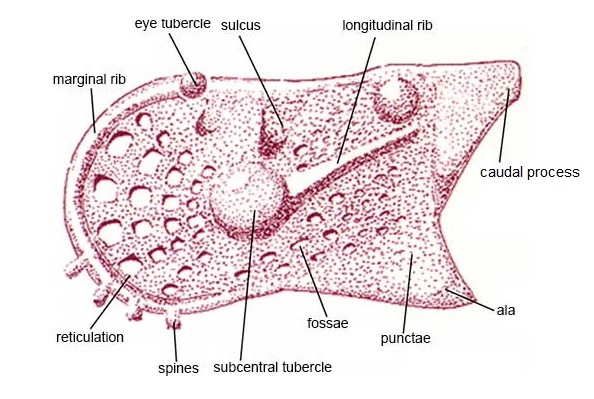

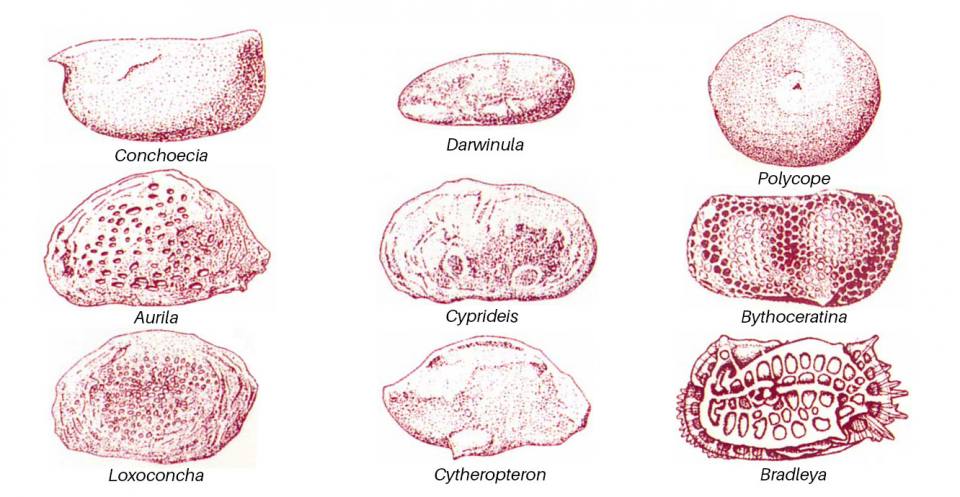

The carapace varies considerably in shape, from elongate to oval, rounded to acutely pointed. The surface of the carapace may also have various characteristics. It may be smooth, punctate (pitted) or reticulate (net-like hollows) and may have ribs, spines, tubercles (knobs), lobes, a sulcus (furrow) or ala (a wing-like projection).

Unlike most crustaceans, ostracods are not segmented, so the head and body merge into one. They usually have seven pairs of limbs, or appendages, which are adapted for locomotion (swimming or crawling), grasping, cleaning the carapace, feeding, or as sensory organs. Some ostracods have eyes, others are blind; all have minute hairs (setae), which protrude through the pores and are used for sensory purposes.

Young ostracods usually (although not always) hatch from eggs in the spring. As the juvenile grows, it moults its carapace and grows a new one, just like crabs and other crustaceans. This generally happens eight times before the animal becomes an adult and may take as little as 30 days for some freshwater species, or up to three years for some marine ostracods. Females are more rounded and three to ten times more numerous than males. Some have brood pouches in which to care for their young. In some species, only females occur and reproduction is parthenogenetic.

Environment

Today, ostracods are found living in every aquatic environment: on the floor of the deep oceans or swimming in the waters above; in the shallow water of the sea shore or estuaries; in the fresh waters of rivers, lakes and ponds; even onshore, in wet, marshy areas of some river estuaries. Some ostracods also inhabit temporary water bodies; their eggs are able to survive when the pond dries up in summer. Geological evidence indicates that, in the past, ostracods lived in similarly diverse environments.

With the exception of Conchoecia (a myodocopid), all the ostracods on this diagram are podocopids; lengths vary from 0.7 to 1 mm. Chris Wardle, BGS ©UKRI.

The environment controls the types of species found. Salinity and water temperature are very important. Many species of ostracods are found in the shallow waters around the coast, because many habitats are to be found there: weeds, sands, silts, rock pools, estuary mouths, saline and brackish water lagoons, etc.

Ostracods were, and are, perfectly adapted to their habitat. Smooth, thin-shelled Conchoecia swims in the surface waters of the oceans, while the heavier-shelled Bradleya and Bythoceratina live on the sea bed many metres below. In shallow, nearshore waters, benthonic Aurila, Loxoconcha, Polycope and Cytheropteron live on the weeds, sand and mud that fringe the coasts. Cyprideis lives in the low salinity estuaries and Darwinula may be found in the freshwater lakes and ponds.

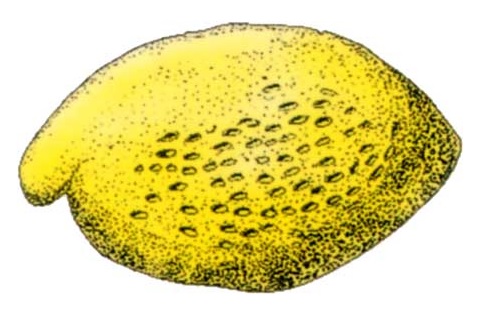

Freshwater ostracods Cypria ophthalmica, 0.65 mm long, crawl about on pond weed looking for algae, bacteria and detritus on which to feed. Note the small eyes. © Microscopy & Analysis.

The geologists’ tool

Fossil ostracods are useful to the palaeontologist as they allow relative dating of the rocks in which they are found and enable correlation to be made. Fossil ostracods also tell us about the environment in which the sediments accumulated, because different types of ostracod lived in different types of environment. Males of some species of ostracods have never been found and it’s thought that reproduction was by parthenogenesis. This is where the young hatch from unfertilised eggs and all are female.

Ostracods through time

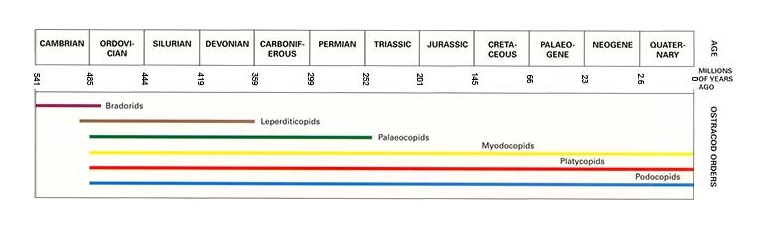

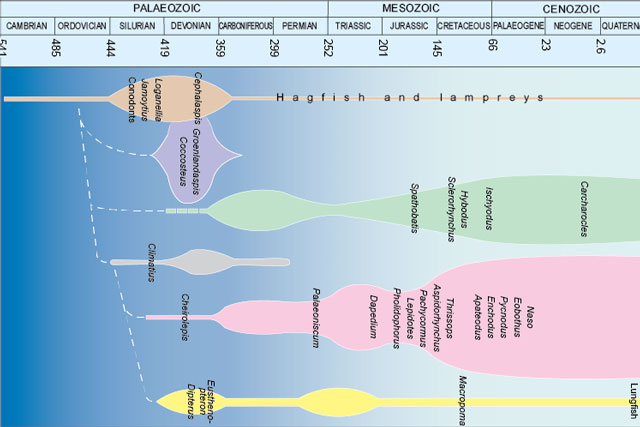

There have been thousands of different species of ostracods during the last 570 million years, although most of them have become extinct during that time. All ostracods can be placed within one of six groups (or ‘orders’). Three are known only from fossils, but species of the other three can be found living today, hundreds of millions of years after they first evolved.

The survival and extinction of ostracod orders through the major divisions of geological time. The ostracods are coloured according to their time bar. Chris Wardle, BGS © UKRI.

Podocopids vary considerably in shape, have an arched dorsal margin and a complex hinge. Their adductor muscle scars are often arranged in a simple vertical row of four. Most living ostracods belong to this group. Chris Wardle, BGS © UKRI.

Platycopids have ovate valves, the right bigger than the left. The 10—18 adductor muscles scars form two rows or a rosette. Chris Wardle, BGS © UKRI.

Myodocopids usually have thin, smooth valves and, sometimes, a rostral incisure (a gap through which the swimming appendages protrude). Chris Wardle, BGS ©UKRI.

Fun facts

Some ostracods are bioluminescent; they glow in the dark. It is said that during the Second World War, Japanese soldiers and sailors would keep cultures of these ostracods in bowls so that they could use the light to read their maps and instruments, but stay concealed. A fishy tale, but apparently true!

It is well known that during early spring, brown trout eat considerable quantities of ostracods. One eminent ostracod worker reported that he once caught a 700 g (1.5 lb) trout that contained an estimated 150 000 ostracods, all of the species Heterocypris reptans (and some of which were still alive). Being a keen fisherman, he made an artificial ‘fly’ to imitate this ostracod and succeeded in catching seven brown trout.

Reference

Wilkinson, I P. 1996. Ostracods: fossil focus. (Nottingham, UK: British Geological Survey.)

You may also be interested in

Discovering Geology

Discovering Geology introduces a range of geoscience topics to school-age students and learners of all ages.

Fossils and geological time

Take a look at the history of the Earth, from its formation over four and a half billion years ago to present times.