Gastropods (formally, Gastropoda) make up a large group (class) of molluscs. They have a muscular foot, eyes, tentacles and a special rasp-like feeding organ called the radula, which is composed of many tiny teeth. Most gastropods have a coiled or conical shell, which may be extremely reduced in some species or lost entirely as in slugs.

Gastropods evolved early in the Cambrian, but since the Palaeogene they have become the most common molluscs, inhabiting both aquatic and terrestrial environments. We focus here on shelled forms that are normally found as fossils:

- Prosobranchia

- Pulmonata

- Opisthobranchia (although these are rather rare)

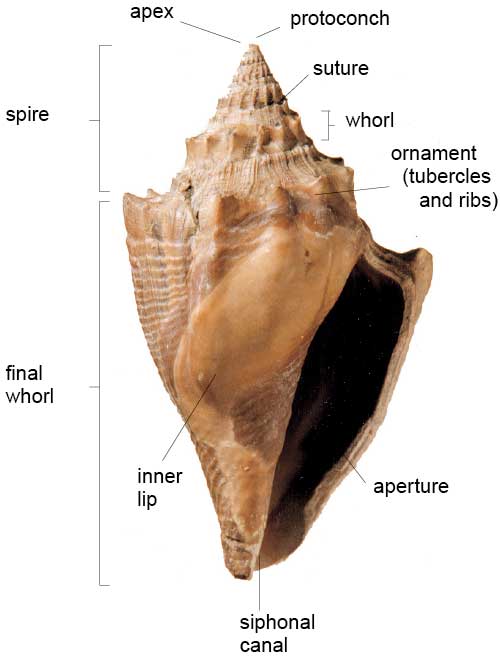

Hexaplex tripteroides, a caenogastropod from the Palaeogene (Eocene) of southern England. BGS © UKRI.

Biology

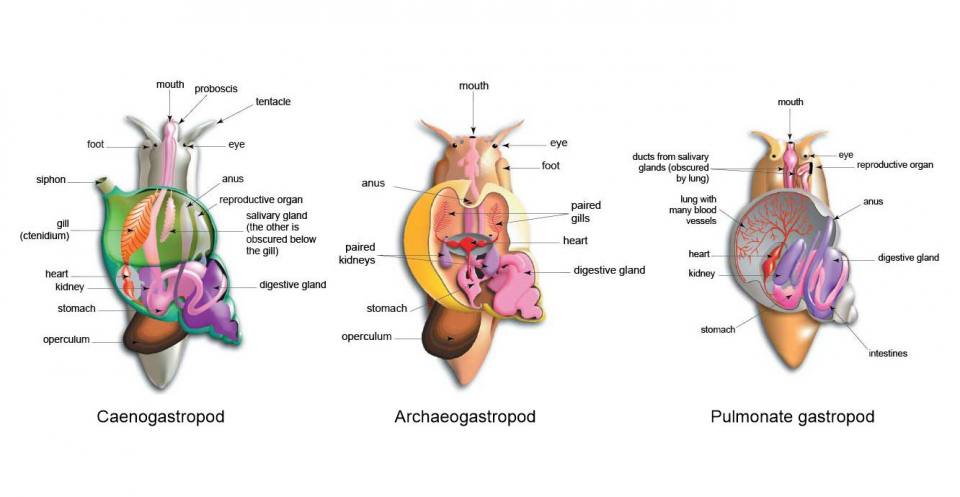

Gastropods can be recognised by their large foot, tentacles, coiled shell (although this is sometimes small or absent) and the presence of torsion, which is where the body is twisted round so that the anus, reproductive organs, mantle cavity and gills all point forwards. Gills occur in most aquatic forms, but in land snails, part of the mantle cavity is closed off to form a lung. Some marine gastropods, especially those that live on a muddy sea floor, have a tube (siphon) protruding from the front of the shell through which clean water is drawn into the mantle cavity.

Reconstruction of aquatic prosobranchs (archaeogastropod and caenogastropod) and a terrestrial pulmonate, with transparent shells to show some of the internal parts. BGS © UKRI.

The shell, which is the part that may be fossilised, is constructed in three layers:

- a thin, coloured outer layer

- a thin, mother-of-pearl inner layer

- a thick, calcareous middle layer

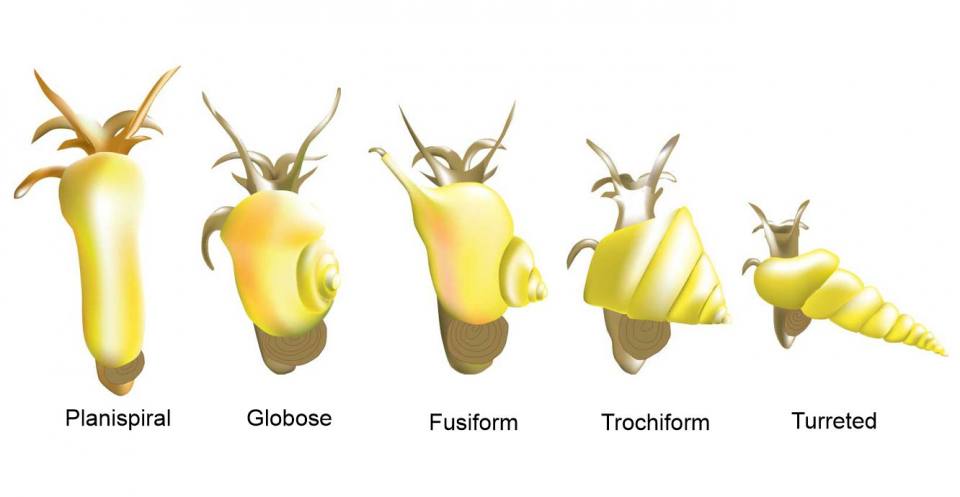

The shell may be planispirally coiled but more usually it is helicoidal, forming a spire with the original juvenile shell (protoconch) preserved at its apex. Sometimes there is a hollow, tube-like canal that holds the siphon during life. Many species carry a horny lid (operculum) on their foot to close the aperture of the shell after retracting inside.

Anatomy and shell shapes

Prosobranchs

Prosobranchs have strong torsion in both males and females. They inhabit marine and fresh water habitats.There are two groups of prosobranchs: archaeogastropods and caenogastropods.

Archaeogastropods have distinctive gills, two auricles in the heart and some have paired gills and kidneys. Caenogastropods have only one gill, one kidney, one auricle in the heart and sometimes a siphon and proboscis.

Pleurotomaria gigantea, an archaeogastropod from the early Cretaceous of southern England. It has a trochiform shell. Modern species are primitive in that they have paired gills. BGS © UKRI.

Pulmonates

Pulmonates inhabit terrestrial environments, although a few have returned to live in fresh water. They have a lung in the mantle cavity, generally lack an operculum and are hermaphrodites (there are no separate males and females).

Galba longiscata (a basommatophore) from southern England lived in fresh waters during the Palaeogene (Eocene to Oligocene). This thin-shelled gastropod grazed on plants growing around lake shores. BGS © UKRI.

There are two groups of pulmonates: basommatophores and stylommatophores. Basommatophores, have a single pair of tentacles with eyes at the base of each and are often found in fresh water environments. Stylommatophores have two pairs of tentacles with the eyes at the end of the posterior pair; the shell may be reduced or lost altogether.

Opisthobranchs

Opisthobranchs may have a coiled shell, but some have lost the torsion characteristic of gastropods and have become bilaterally symmetrical. Their foot is fin-shaped and used for swimming and their shells are very small, thin and fragile; in some species it has been lost entirely. It is for this reason that these gastropods are very rarely found as fossils. They live in marine environments and an example is the pelagic (open sea) pteropod or ‘sea butterfly’.

Diacria trispinosa, a pteropod that swam in the ocean waters of the North Atlantic during the Quaternary. Sometimes millions of pteropod shells accumulate to form an ooze on the ocean floor. BGS © UKRI.

Environment

Gastropods inhabit all aquatic environments from the deepest oceans, where they may live beneath 5 km of water, to small, shallow, fresh water ponds. They are one of the few invertebrates to have colonised the land and can live at altitudes of 6000 m above sea level. As they can live in so many different environments, they have become the most diverse type of mollusc.

The caenogastropod Turritella sulcifera, from Hampshire, southern England, searched for food by burrowing into the muddy sea floor during the Palaeogene (Eocene). BGS © UKRI.

Aquatic gastropods evolved in the Cambrian and began to colonise all the marine habitats. Some crawled over the sea bed, others burrowed into the mud and sand, while yet others preferred to attach themselves to firm surfaces. More recently some began to float or swim and pelagic (open sea) species evolved. These are known as pteropods or sea butterflies.

During the Carboniferous, gastropods began to live in fresh water and terrestrial snails probably evolved from these species. Life out of the water brought two big problems: how to breathe and how to prevent drying out. They solved the first problem by evolving lungs. As they require high humidity and wet conditions to be active, gastropods solved the second problem by aestivation.

As gastropods are classified mainly by the soft parts of their body — the parts that are not preserved — it may be difficult to place fossils into subclasses and orders.

Geological history

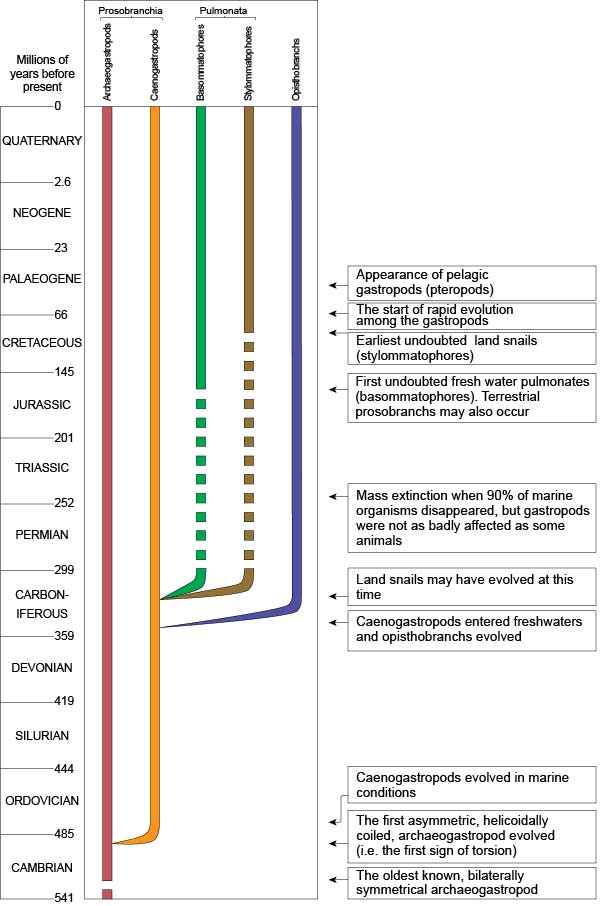

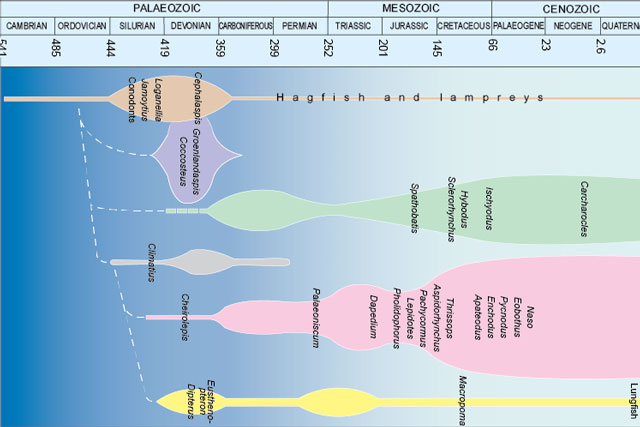

Biological events in gastropod history. BGS ©UKRI. All rights reserved.

The first gastropods evolved from an unknown bilaterally symmetrical mollusc ancestor in the early Cambrian, but they became common during Palaeozoic times. Between the Cambrian and Devonian, gastropods were entirely marine, but by the Carboniferous some had entered non-marine waters and land snails may have evolved by the late Carboniferous.

At the end of Permian times, there was a mass extinction event and gastropods did not escape. However, with the Mesozoic, many new species evolved, including high-spired, burrowing forms and some gastropods grew to an enormous size (e.g. some of the cowry shells). Gastropods had colonised marine, brackish and fresh water habitats as well as the land by this time.

The maximum development of the gastropods has been in the last 65 million years following the end-Cretaceous mass extinction event. This was a time of rapid evolutionary radiation of benthic (bottom-dwelling) species and, starting in the early Eocene, pelagic (swimming) pteropods evolved as well. Terrestrial gastropods became particularly common during the Palaeogene and it was probably at this time that shell-less gastropods also developed, but they are not found as fossils.

In all, about 105 000 living and 15 000 fossil gastropod species are known.

Fun facts

The Roman or edible snail (Helix pomatia), Britain’s largest land snail, grows up to 10 cm in length. Snails were one of the favourite foods of the Roman gourmet and they appeared on the menus of feasts marking special occasions. It was a Roman called Fulvius Lupinus who first discovered that snails tasted best when they were fattened up on milk until they became so large that they could not retract into their shell. © Creative Commons, HSP90.

Seaside rock

Limpets cause about 30 per cent of the erosion along the coast of Sussex, England. They eat chalk as they graze on the algae and hollow out places to shelter during low tide. Each limpet eats almost 6 g of rock a year and when you consider how many millions of limpets there are, this amounts to a lot of chalk! The rocks of the Sussex foreshore are being lowered by up to 1.5 mm per year and this can contribute to damaged sea defences and landslides.

Common limpets, Patella vulgata, can cause a surprising amount of erosion as they nibble away at features such as Chalk cliffs at a rate of up to 1.5 mm per year. Creative Commons © Janek Pfeifer.

Bigfoot

The biggest living gastropod is the ‘sea hare’ Aplysia californicus, which is found off California and known to gt to over 7 kg. By comparison, the 27 cm-long African giant snail Achatina fulica, the largest land snail, weighs only 0/5 kg.

Filholia elliptica, from the Oligocene of southern England, is believed to have laid some of the largest known fossil gastropod eggs, which were up to 30 mm long. BGS ©UKRI.

3D fossil models

Horiostoma discors var. mariae (Silurian, Wenlock). See 3D fossils online. GB3D Type Fossils. BGS © UKRI.

Many of the fossils in the BGS palaeontology collections are available to view and download as 3D models. To view this fossil, or others like it, in 3D visit GB3D Type Fossils.

Reference

Wilkinson, I P. 2002. Gastropods: fossil focus. (Nottingham, UK: British Geological Survey.)

You may also be interested in

Discovering Geology

Discovering Geology introduces a range of geoscience topics to school-age students and learners of all ages.

Fossils and geological time

Take a look at the history of the Earth, from its formation over four and a half billion years ago to present times.