Echinoids have lived in the seas since the Late Ordovician, about 450 million years ago, which is about 220 million years before dinosaurs appeared. The remains and traces of these animals were buried in sediment that later hardened into rock, preserving them as fossils. The living representatives of echinoids are the familiar sea urchins that inhabit many shallow coastal waters of the world. Fossil echinoids closely resemble some living sea urchins, which helps us to understand how they must have lived.

A modern sea urchin. © Public domain. NOAA OKEANOS Explorer Program, 2013 North-east US Canyons Expedition.

The animal

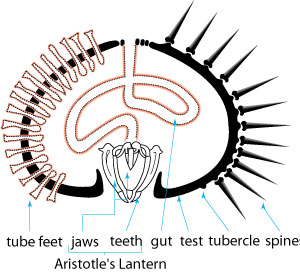

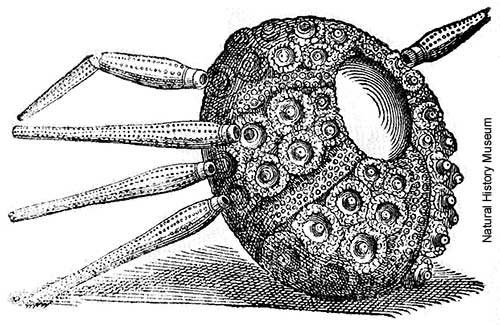

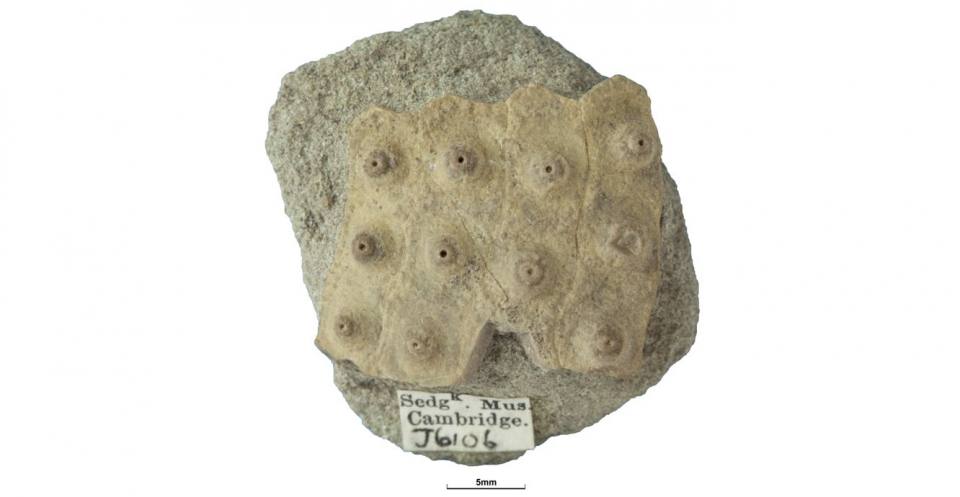

Echinoids are marine animals belonging to the phylum Echinodermata and the class Echinoidea. They have a hard shell (referred to as a test) covered with small knobs (tubercles) to which spines are attached in living echinoids. The test and spines are the parts normally found as fossils.

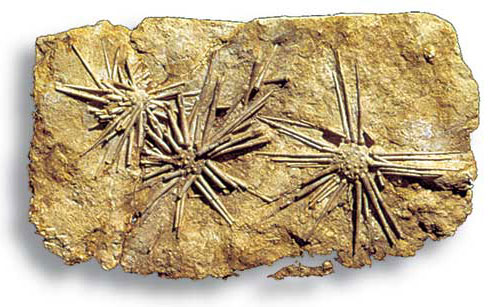

Echinoid tests have a variety of shapes; they can be globular or flattened, rounded or heart-shaped. The most important function of the test was to support and protect the soft body inside. The spines, held in place by soft tissue covering the test during life, usually became detached and fossilised separately. Occasionally, when fossilisation was rapid, the spines and test are found preserved together.

The test and spines are made of the mineral calcite. The test contains hundreds of calcite plates, loosely held together in Palaeozoic species but rigidly fused together in most species since the Mesozoic. The plates are arranged so that the test appears to consist of wedge-shaped segments, usually separated by narrow bands of tiny holes (pores) that radiate out across the test.

Hemicidaris from the Jurassic, with elongate spines. BGS © UKRI.

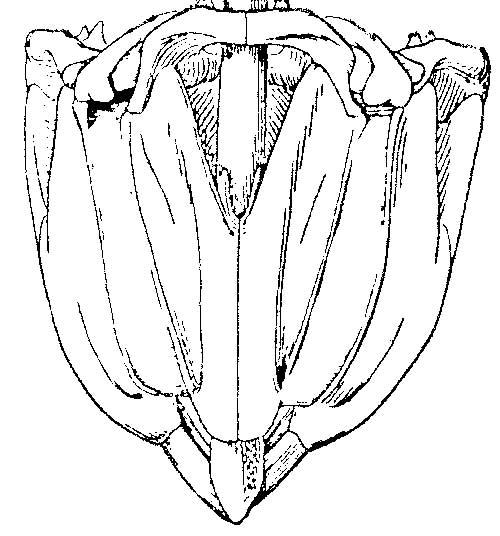

Calcite also forms the powerful downward-pointing teeth found in some types of living and fossil echinoids. Concentrations of magnesium in the tips of the teeth add extra strength for scraping food items from rock surfaces.

Spines, some poison-tipped, help protect echinoids from their many predators, which include other echinoids, crustaceans, octopuses and fish. Some fossil echinoids made themselves less palatable as prey by having large, solid spines. Echinoids also use their spines for moving around the seabed and, in some groups, they are specially adapted for burrowing.

Echinoids and their enemies: a seascape showing the kinds of environments inhabited by modern and fossil echinoids. Burrowing sea urchins (1 and 2) conceal themselves from predators, while non-burrowing types (3 and 4) cling to rocky surfaces and have defensive spines to protect against fish, lobster, starfish and octopus. © Richard Bell.

In the Mesozoic, echinoids evolved into a variety of shapes adapted to burrowing beneath the seabed. Concealed from predators, they used numerous bristle-like spines for ploughing through the sediment rather than for protection and some probably resembled the modern-day Echinocardium.

Echinocardium cordatum (Pennant, 1777) Recent; also known as the sea potato. Its bristle-like spines on its underside are used for burrowing (left; © Creative commons, Cwmhiraeth). Artist’s interpretation (right; BGS © UKRI).

Some echinoids wandered the seabed scavenging a wide variety of food, including algae, plants and encrusting organisms. Suckered, tentacle-like organs (tube feet) extended through the pores in the test, their powerful grip preventing the echinoid from being overturned in rough water and enabling it to climb rock faces. as well as assisting in feeding and respiration.

Food particles were extracted from the sediment swallowed by burrowing echinoids and, in some types, holes and frills in the test and grooves around the mouth helped to maximise food-gathering ability.

The geologists’ tool

Fossil echinoids are a reliable indication that the rocks containing them were formed in a marine environment. However, they can also be a useful guide to the age of the rocks in which they occur. Their remains are sometimes more common and better preserved than other types of fossils normally used for biostratigraphy. This is the case in the strata of Late Cretaceous age, known as the Chalk Group, which form the famous White Cliffs of Dover.

Pioneering work by geologist A W Rowe (1858–1926) and R M Brydone (1873–1943) in southern England showed that different types of echinoid could be used to divide parts of the Chalk into biozones and sub-biozones of different ages. This is particularly important for the purposes of correlation in the Chalk, which superficially has a very uniform appearance.

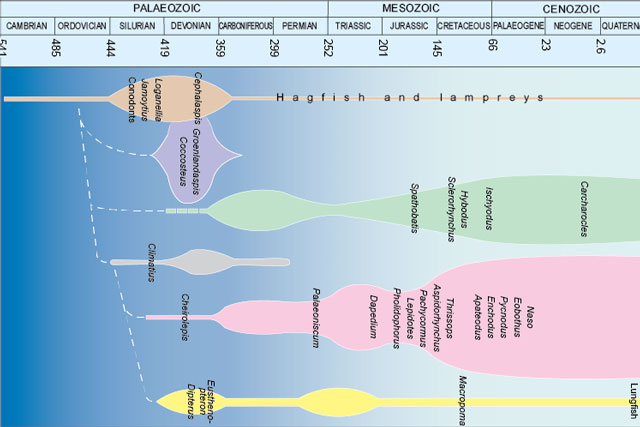

Palaeozoic echinoids are less useful to geologists because they tend to be rarer; their primitive tests often quickly disintegrated before fossilisation could occur.

Temnocidaris (Stereocidaris) sceptrifera sceptrifera (Mantell, 1822), a long-ranging Late Cretaceous echinoid. BGS © UKRI.

Echinoids through time

Echinoids are abundant today and fossil echinoids are common in rocks of Jurassic and Cretaceous age, especially the Late Cretaceous Chalk.

Myths and legends

The Echinodermata take their name from the Greek words for spiny skin, a very conspicuous feature of many living echinoids. Since ancient times they have been revered as objects of religious or superstitious power.

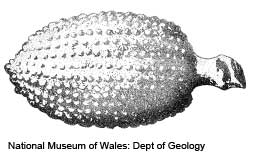

Early drawing of a fossil echinoid. © Natural History Museum.

The name Aristotle’s Lantern for the complex jaw apparatus of some sea urchins was first coined by Klein in the 18th century, because of its similarity to a Greek lantern and Aristotle’s fascination for the sea urchin.

Sketch of Aristotle’s lantern. BGS © UKRI.

Echinoids have been used in traditional remedies for stomach disorders and, in Roman times, were considered an antidote to snake bites. Spines of the Cretaceous echinoid Balanocidaris glandifera, bearing a superficially resemblance to a bladder, were used to treat gall, bladder and kidney ailments and those of the Recent Heterocentrotus mammillatus (Linnaeus, 1758) were ground up and mixed with vinegar to treat ear problems.

Spine of the Cretaceous echinoid Balanocidaris glandifera. © National Museum of Wales.

3D fossil models

Heterocidaris wickense Wright. (Jurassic , Bathonian – Aalenian). BGS © UKRI.

Many of the fossils in the BGS palaeontology collections are available to view and download as 3D models. To view this fossil, or others like it, in 3D visit GB3D Type Fossils.

Reference

Woods, M A. 1999. Echinoids: fossil focus. (Nottingham, UK: British Geological Survey.)

You may also be interested in

Discovering Geology

Discovering Geology introduces a range of geoscience topics to school-age students and learners of all ages.

Fossils and geological time

Take a look at the history of the Earth, from its formation over four and a half billion years ago to present times.