Crinoids are marine animals belonging to the phylum Echinodermata and the class Crinoidea. They are an ancient fossil group that first appeared in the seas of the mid Cambrian, about 300 million years before dinosaurs. They flourished in the Palaeozoic and Mesozoic eras and some survive to the present day. Although sometimes different in appearance from their fossil ancestors, living forms provide clues about how fossil crinoids must have lived.

Periechocrinus, a Silurian crinoid. BGS © UKRI.

The animal

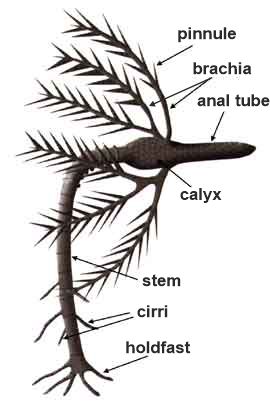

An array of branching arms (brachia) is arranged around the top of a globe-shaped, cup-like structure (calyx) containing the main body of the animal. In many fossil forms, the calyx was attached to a flexible stem that was anchored to the sea bed.

Anatomy and feeding position of a stemmed crinoid. The water current flow is left to right. BGS © UKRI.

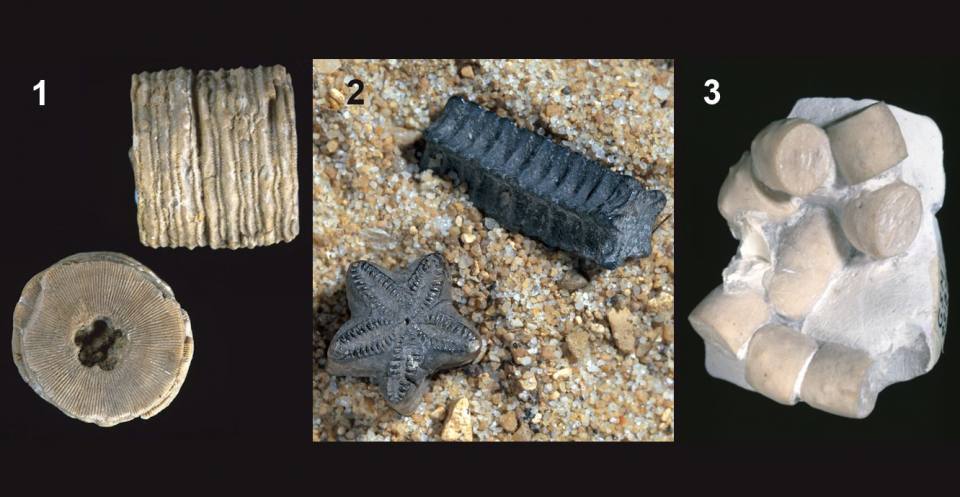

The skeleton is made of the mineral calcite and consists of hundreds of individual plates of different shapes and sizes. Decay of the soft tissue that held many of these plates together means that complete specimens are rare, but parts of the stem are common fossils.

A living crinoid, Gulf of Aqaba, Red Sea. Public domain. (NOOA, Mohammed Al Momany, Aqaba.)

The calyx is made of polygonal plates, arranged differently in different groups of crinoids. It contained the mouth, to which food was conveyed via grooves in the brachia. In some fossil crinoids the top of the calyx was a flexible membrane, but in others it is preserved as a rigid dome, and may have an elongated anal tube for the disposal of waste products.

The stem typically consisted of disc-like plates (columnals) stacked on top of each other. Individual columnals were rounded, oval, square, five-sided or star-shaped, and some plates were decorated with petal-like designs. The different shapes of crinoid stem plates are useful for classification, but some fossil crinoids, like many modern forms, lack stems.

Crinoid stem columnals: 1 Crotalocrinites (Silurian), 2 Pentacrinites (Jurassic), 3 Bourgueticrinus (Cretaceous). BGS © UKRI.

Fossil crinoids abounded in shallow water, particularly in the late Silurian and early Carboniferous. Stemmed forms could bend towards water currents and use their brachia as a net to trap food particles. Side branches to the brachia (called pinnules) improved this ability in some groups, and very long stemmed forms may have exploited the best food supply from a range of water depths. Crinoid stems with movable appendages (cirri), or possibly a prehensile capability, allowed temporary anchorage where food was plentiful.

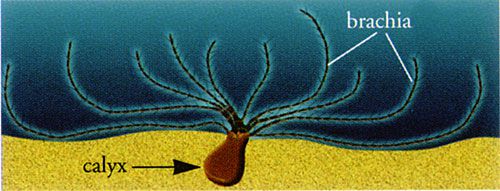

Occasionally in the Palaeozoic and more commonly in the Mesozoic, stemless forms of crinoids evolved, allowing them to search the sea floor for better feeding conditions and escape environments with high numbers of predators. The small, stemless Saccocoma (Jurassic to Cretaceous) was free-swimming, but the much larger stemless Uintacrinus and Marsupites (Cretaceous) probably rested on the seabed with their brachia outstretched as a food collecting bowl.

Probable living position of Uintacrinus and Marsupites. BGS © UKRI. All rights reserved.

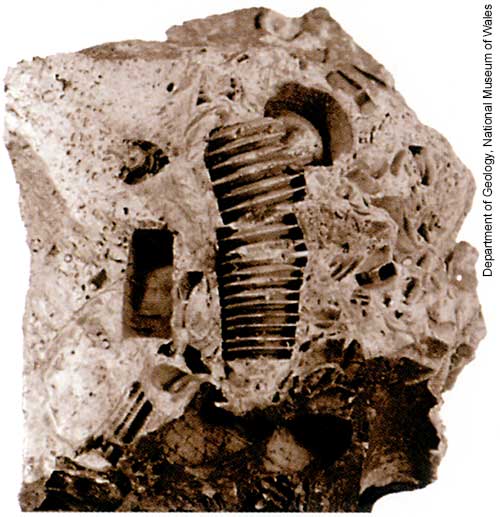

Pentacrinites briareus (Miller, 1821) early Jurassic. A rare example of complete preservation of a crinoid skeleton. BGS © UKRI.

The geologists’ tool

Fossil crinoids indicate that the rocks containing their remains were formed in a marine environment and, where abundant in Palaeozoic rocks, they suggest the former existence of shallow water conditions. In the early Carboniferous, their rich remains (particularly stem fragments) were solidified into rock called crinoidal limestone. Rare occurrences of complete fossilised crinoids indicate rapid burial in quiet, possibly poorly oxygenated waters.

Pentacrinites briareus forming crinoidal limestone. BGS © UKRI.

Occasionally, crinoids can be a useful guide to the age of the rocks in which they occur. This is the case in the strata the late Cretaceous the Chalk Group, which form the famous White Cliffs of Dover. Species of Uintacrinus, Marsupites, and Applinocrinus are so abundant over four narrow intervals in the Chalk that they have been used to define biozones and subbiozones.

Complete specimen of Uintacrinus socialis. © Natural History Museum.

Crinoids through time

Crinoids are common fossils in the Silurian rocks of Shropshire, the early Carboniferous rocks of Derbyshire and Yorkshire and the Jurassic rocks of the Dorset and Yorkshire coasts.

Myths and legends

Crinoids are sometimes referred to as sea lillies because of their resemblance to a plant or flower. In parts of England, the columnals forming the stem are called fairy money. Star-shaped examples of these were associated with the sun by ancient peoples and given religious significance. Robert Plot (1640—1696) named these ‘stellate’ forms star stones.

Star stones. BGS © UKRI.

Polished slabs of crinoidal limestone make attractive ornamental stone. In Derbyshire, the limestone sometimes contains internal moulds of crinoid stem fragments, which have a distinctive screw-like thread pattern and have been called screwstones.

Screwstone. © National Museum of Wales.

The columnals forming the stem can sometimes be threaded into a necklace and the name St Cuthbert’s beads refers to the saint associated with the legend of making them into rosaries.

3D fossil models

Amphoracrinus portlocki (Carboniferous Period, Dinantian Subsystem (326.4 – 359.2 Ma). See 3D fossils online. BGS © UKRI.

Many of the fossils in the BGS palaeontology collections are available to view and download as 3D models. To view this fossil, or others like it, in 3D visit GB3D Type Fossils.

Reference

Woods, M A. 1999. Crinoids: fossil focus. (Nottingham, UK: British Geological Survey.)

You may also be interested in

Discovering Geology

Discovering Geology introduces a range of geoscience topics to school-age students and learners of all ages.