Corals (or more formally, Zoantharia) are marine animals related sea anemones that lack a free-swimming (medusoid) stage. They have mobile larvae that become sessile (fixed to one place) after a few days.

Colony of living coral, Tubastrea sp. (Public domain; photo collection of Dr James P McVey, NOAA Sea Grant Program.)

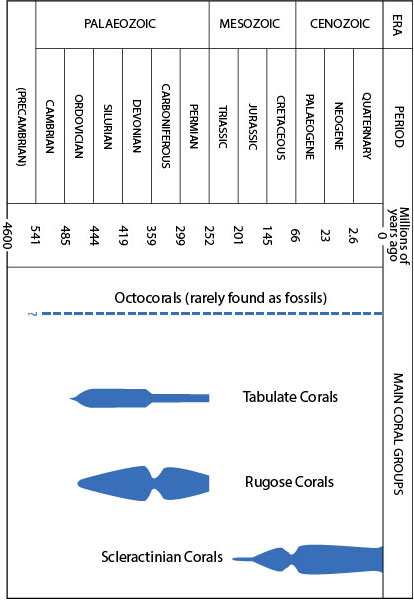

The oldest known corals lived during the Cambrian, more than 500 million years ago, and are still found living today. Some, like octocorals (which have has eight ‘arms’) are soft bodied and rarely preserved as fossils, but others secrete a hard, calcarous (made of calcium carbinate) skeleton and are thus important rock-forming organisms.

We focus here on the three groups, or orders, of corals that are most frequently found as fossils: Rugosa, Tabulata and Scleractinia.

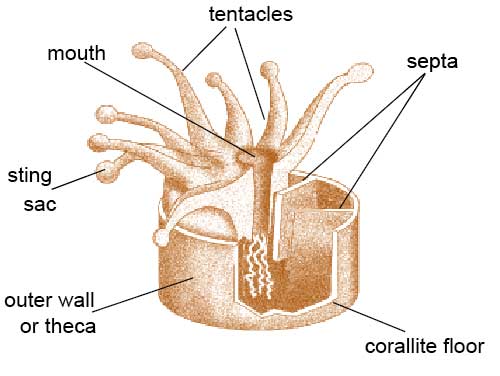

The animal

Corals comprise a soft-bodied animal called a polyp that lives in a calcareous skeleton or corallum. Food is taken in and waste products are discharged through the mouth, which is surrounded by tentacles with poisonous stings.

An imaginary solitary coral, partly broken away, to show the calcareous structure of the corallite and the living animal (polyp). BGS ©UKRI.

The polyp removes calcium carbonate from the sea water to create a skeleton of calcite or aragonite, although when fossilised, aragonite often changes to calcite. The corallite in which the polyp lives is strengthened by septa (radiating plates), tabulae (corallite floors that build up one on the other) and sometimes dissepiments (small concentrically arranged plates between the septa). Corals may live alone (solitary) or in a group (colonial or compound).

Rugose corals are solitary or colonial types with bilateral symmetry. They have a hollow in the top surface (calice) in which the polyp sits, together with numerous tabulae, septa (the major ones being arranged in groups of four), dissepiments and, in some, a central calcareous rod (columella).

Tabulate corals are all colonial and have many closely spaced tabulae, but septa and dissepiments are either absent or very weak. Their fossils are often preserved as a cluster of long, slender tubes (corallites).

Scleractinian corals may be solitary or colonial. They have a very porous or spongy skeleton made of aragonite that is strengthened by radiating septa (the main ones being arranged in groups of six), dissepiments and sometimes a columella.

Flabellum woodi, a small solitary scleractinian coral that grew to about 2 cm across. BGS © UKRI.

Flabellum woodi, a small solitary scleractinian coral that grew to about 2 cm across. BGS © UKRI.

Acropora, a modern scleractinian coral from the latest Quaternary of the Pacific showing the spongy aragonite skeleton. BGS © UKRI.

Acropora, a modern scleractinian coral from the latest Quaternary of the Pacific showing the spongy aragonite skeleton. BGS © UKRI.

Environment

Corals live in marine water, at most depths and latitudes. They have been found in water 6000 m deep, but are most common at depths of less than 500 m. At these depths, the water temperature may be close to 0°C, but corals are most common between 5° and 10°C. Deeper water corals are mainly solitary, although some, such as Lophelia, are colonial and form thickets and banks.

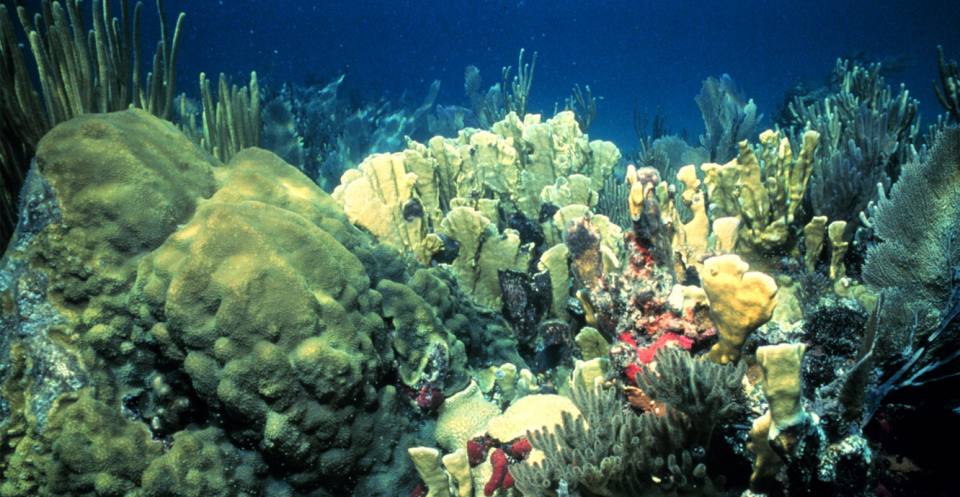

Corals reefs on the other hand, are restricted to the warmer regions of the world’s oceans such as the Seychelles, in the Indian Ocean, and Australia. They gradually add skeletal calcium carbonate to the existing reefs to build huge structures in well-lit, warm, tropical waters, clear of land-derived sediment. Reef-building corals favour water depths of less than 10–20 m and temperatures between 25° and 29°C.

A living coral reef in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. ©Public domain. NOOA, Mike White, Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.

Ancient coral reefs

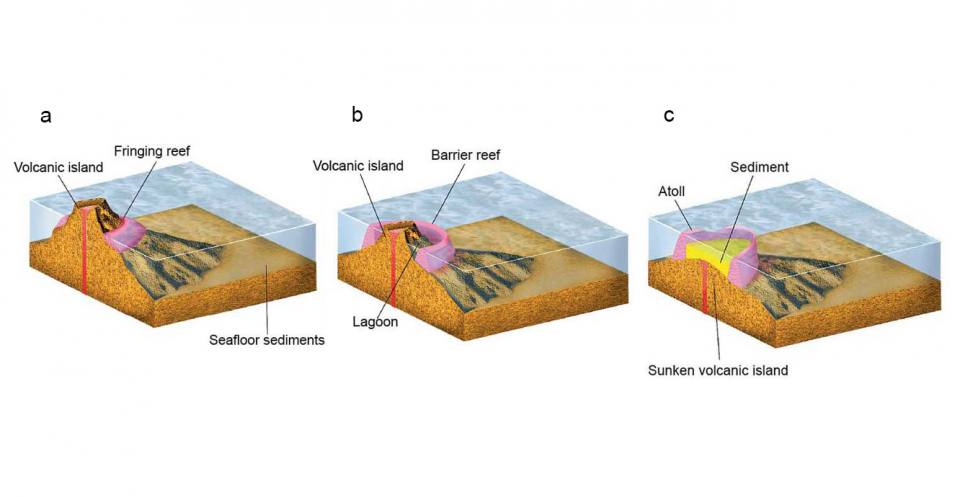

Tabulate and rugose corals built mounds and thickets during the Palaeozoic, contributing to reef building, and fossils are commonly seen in Silurian to Carboniferous rocks of Britain. On a worldwide scale, they seem to have lived in equatorial latitudes, similar to modern forms. Since the Triassic, scleractinian corals have become reef builders. Coral reefs range in size from a few metres to hundreds of kilometres, but they fall into three main types.

- Fringing reef: forms when coral reefs grow in warm, shallow-coastal waters. Sudden changes of sea level, such as during the last ice age, kill the coral, but where sea level rises (or the land sinks) at a slow rate, coral growth can keep pace. This can happen around an island formed by a volcano as the land subsides after volcanic activity stops.

- Barrier reef: as a volcanic island slowly subsides, the reef grows upwards at the same rate. In this way the reef forms a barrier reef a little way from the shore and with a lagoon behind it.

- Atoll: continued subsidence (or a rise in sea level) causes the volcanic island to disappear below the waves. The reef, however, continues to grow, taking on a roughly circular shape (an atoll) (and enclosing a lagoon, floored by sediment and reef debris.

Formation of coral reefs: (a) fringing reef; (b) barrier reef and (c) atoll. BGS © UKRI.

Corals through time

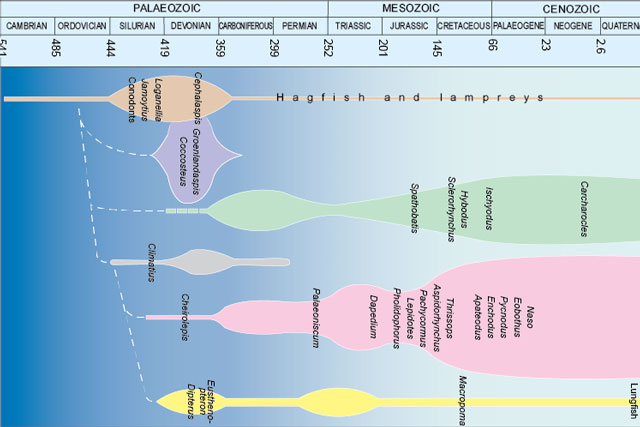

Rugose and tabulate corals were common in the Palaeozoic. However, a mass extinction event took place at the end of the Permian, when over 90 per cent of all invertebrates became extinct, including all tabulate and rugose corals. The reason seems to have been due to the formation of the supercontinent Pangaea and the disappearance of environmental niches.

The distribution of corals through time. BGS © UKRI.

This was also a time of increased aridity, with changes in ocean currents, more competition for less space on the continental shelf, widespread occurrence of evaporite deposits, intense volcanicity and changes in sea level. Scleractinian corals, which evolved during the Triassic, replaced the extinct groups.

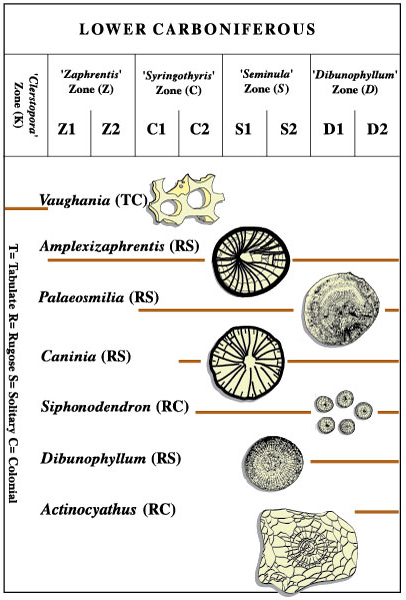

Coral zones in the early British Carboniferous. BGS © UKRI.

One of the most important uses of fossils is in biostratigraphy, where short-lived fossil species are used to date the rocks in which they are found. Coral species are usually too long-lived to be useful in this way, but early Carboniferous rocks of Britain can be subdivided into zones defined by the first appearance of key corals they contain. These zones can also be traced throughout western Europe.

The coral clock

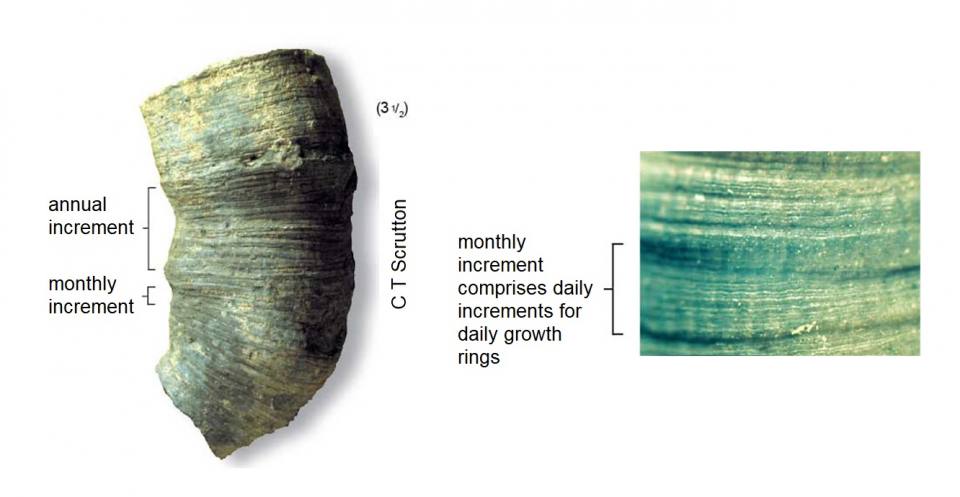

When corals are examined under a microscope, their outer surface can be seen to be made up of hundreds of ridges (about 200 per centimetre). Each ridge was formed in a single day as the coral grew. Modern corals, such as Manicina and Lophelia, have about 360 growth ridges per year on average (it varies a little as they do not grow during breeding or bad environmental conditions), but Devonian corals like Heliophyllum and Eridophyllum grew 400 ridges each year on average. This is because the Earth’s rotation has slowed down so that there are 35–40 fewer days in the year now compared to Devonian times.

Heliophyllum halli (left) lived during mid Devonian times in Michigan, USA. Annual and monthly growth rings can be recognised. Daily growth rings of Heliophyllum halli (right) show there were about 400 days in the year during the Devonian period. BGS © UKRI.

3D fossils models

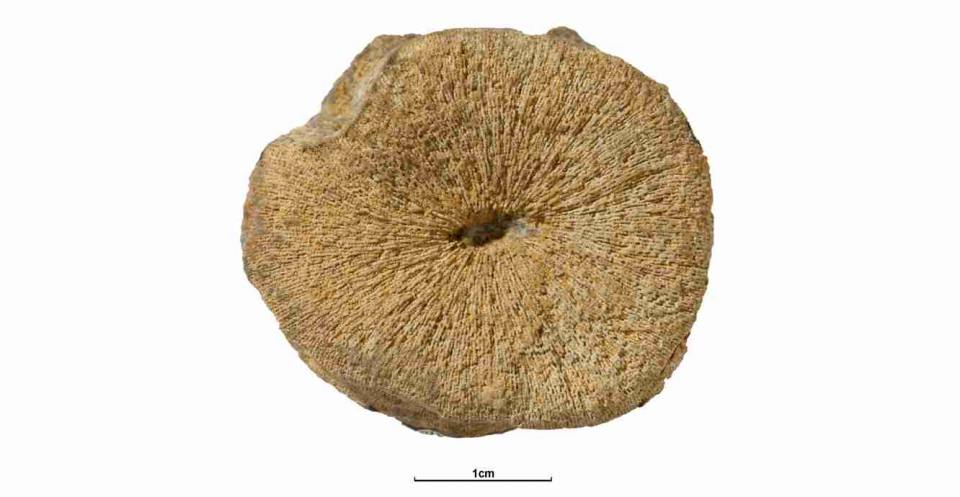

Cyclolites cupuliformis (Jurassic, Pliensbachian). BGS © UKRI.

Many of the fossils in the BGS palaeontology collections are available to view and download as 3D models. To view this fossil, or others like it, in 3D visit GB3D Type Fossils.

Reference

Wilkinson, I P, and Scrutton, C. 2000. Corals: fossil focus. (Nottingham, UK: British Geological Survey.)

You may also be interested in

Discovering Geology

Discovering Geology introduces a range of geoscience topics to school-age students and learners of all ages.

Fossils and geological time

Take a look at the history of the Earth, from its formation over four and a half billion years ago to present times.