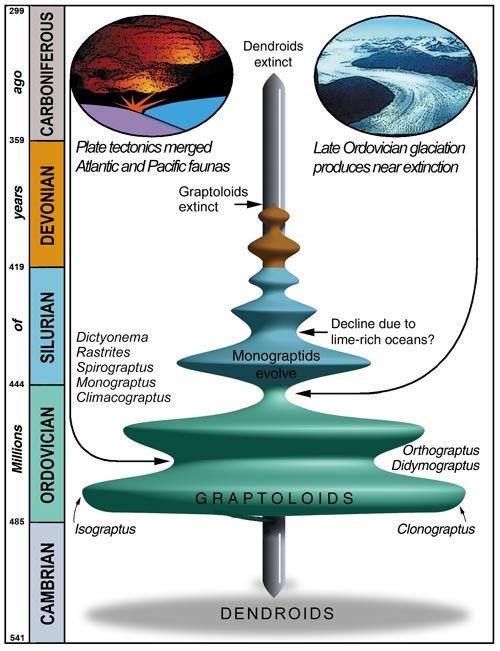

Fossil graptolites are thin, often shiny, markings on rock surfaces that look like pencil marks, and their name comes from the Greek for ‘writing in the rocks’. They are the remains of intricate colonies, some of which accommodated up to 5000 individual animals; these individuals lived in a skeleton of collagen, similar to the material from which our fingernails are made. We focus on the two main groups: dendroids and planktonic graptolites.

They lived between the Cambrian and Carboniferous periods, about 520 to 350 million years ago.

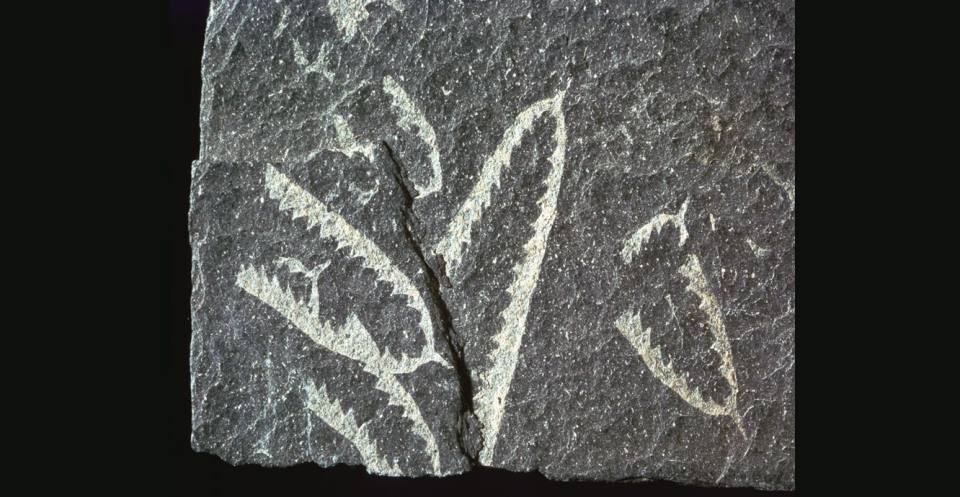

Didymograptus ‘bifidus’ , from the Ordovician of South Wales, was about 2 cm long. BGS © UKRI.

The animal

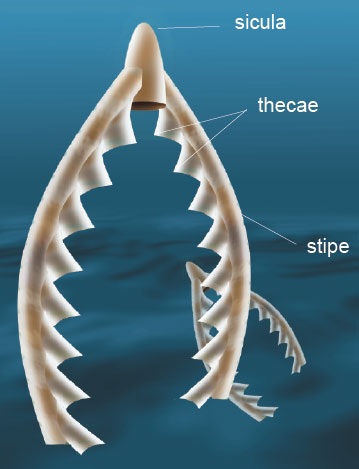

Graptolites were colonial animals that lived in an interconnected system of tubes. From an initial ’embryonic’, cone-like tube (the sicula), subsequent tubes (thecae) are arranged in branches (stipes) to make up the whole colony (rhabdosome). Each individual animal is called a zooid.

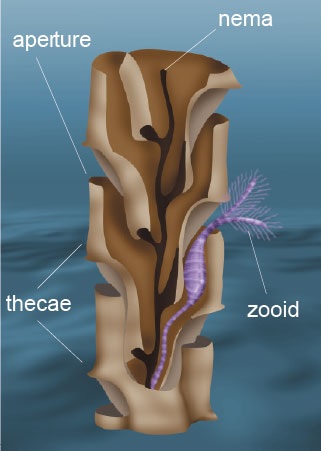

A close-up of the thecae of Climacograptus partly cut away to show the internal structure of the interconnecting tubes and one of the zooids. The thread-like, central nema (or virgula), which may protrude some distance beyond the stipes, may have been used for attachment when juvenile, for strengthening or to attach a floatation device or vane. BGS © UKRI.

Environment

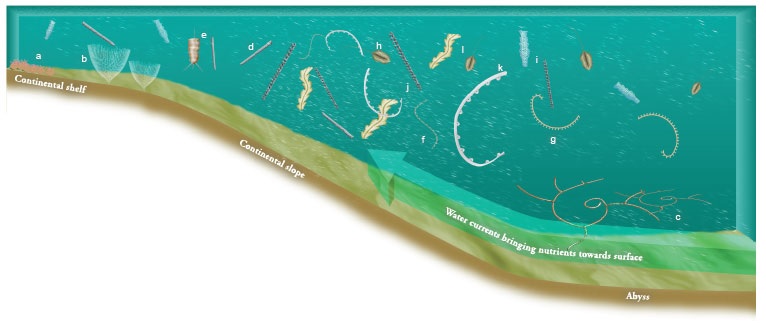

The earliest graptolites lived on the sea bed, attached to boulders or forming upright cones rooted into soft mud. This is still the lifestyle of the living relatives of graptolites.

The earliest graptolites lived on the sea bed (a and b) while later forms were free floating (c–l). BGS © UKRI.

At the beginning of the Ordovician period graptolites became free floating. They were amongst the first animals to colonise the open sea and were able to exploit enormous untapped reserves of food (single-celled organisms) in the upper layers of the oceans. Different species evolved rapidly in order to exploit these food reserves and in response to the new challenge of a floating life.

Graptolites were common where food was abundant, especially in upwelling currents, where deep water, with its load of nutrients, is forced upwards and into shallower waters in areas such as the tropics and at the edge of the continental shelf. Some were deep-water specialists, whilst others were opportunists seeking out temporary supplies of food. Some colonies evolved into enormous harvesting arrays, capable of living to a significant age, perhaps up to 20 years. Others evolved into slim, short colonies or into gently curved forms, which rotated through the water as they fed. Using the distribution of fossil graptolites, we can begin to reconstruct the oceans in which they lived.

A floating life is a challenge; graptolites responded to this by evolving a range of hydrodynamic strategies. Long nemas evolved to retard sinking and hooked, spiny and net-like forms appeared, which would have had a high drag so that they moved slowly. The zooids may have helped the colony to move and possibly secreted gas or low-density fat to help the colony to rise through the water.

Modern relatives

Although graptolites are now extinct, living marine animals called pterobranchs appear to be closely related. Pterobranchs do not grow their tube-like skeleton in the same, passive way as we grow our bones or an oyster makes its shell. Rather, the pterobranch zooids actively construct them, much as a spider weaves its web or termites build their nest. Graptolites probably did the same: the criss-crossing bandages in the outer layer of a theca, which look rather like the bandages wrapping an Egyptian mummy, were apparently ‘trowelled’ on by a secretory organ akin to that of pterobranchs.

Cephalodiscus gracilis, a living pterobranch thought to be related to graptolites. Two zooids have extended their feathery filtering nets to feed. BGS © UKRI.

The geologists’ tool

Graptolites are excellent geological time-keepers; they can be used to date the rocks in which they are found. They evolved quickly and assumed a wealth of easily recognisable shapes. Many of these evolutionary steps, which can be traced around much of the world, define periods of time. Some of these time-slices are only a few hundred thousand years long, which, to a geologist, amounts to pinpoint accuracy given that all this took place hundreds of millions of years ago!

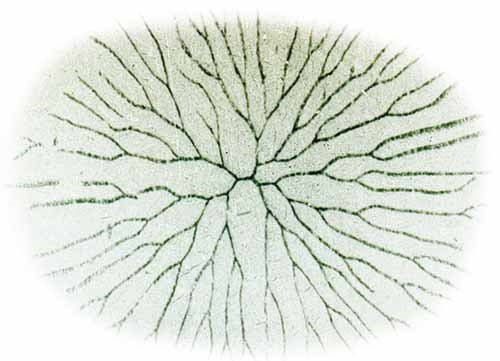

Dendroids

Dictyonema (from the Silurian Period) had many branches and thousands of zooids in its cone-shaped colony. © The British and Irish Graptolite Group (BIG G).

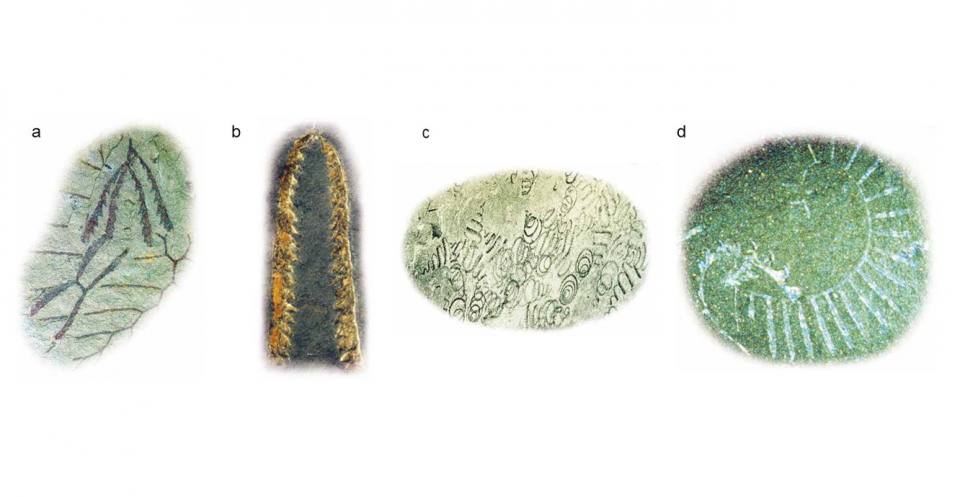

Anisograptids such as the Ordovician Clonograptus are transitional between dendroids and graptoloids. Most of these ‘planktonc dendroids’ had two types of theca, but fewer stipes. Dendroids first evolved in the Cambrian and lived rooted to the sea bed. Dendroids had two types of thecae, possibly for males and females. © The British and Irish Graptolite Group (BIG G).

Graptoloids

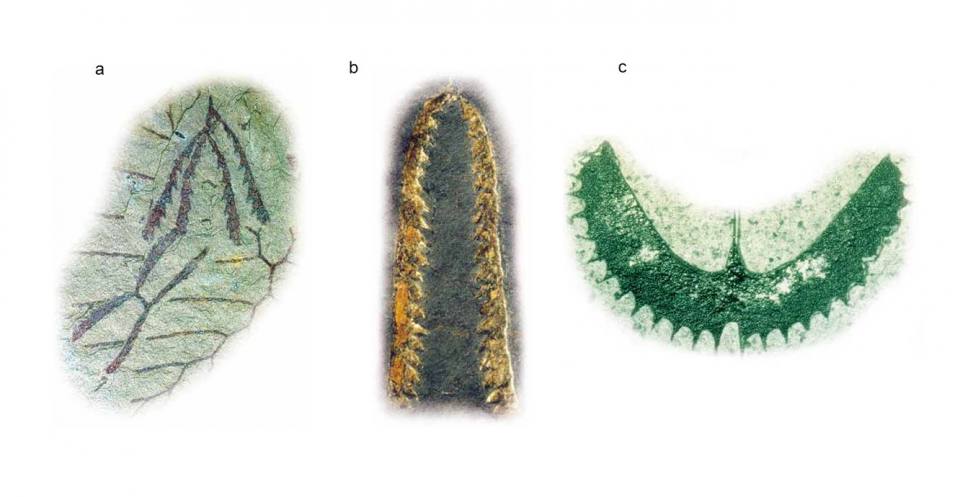

Graptoloids were all planktonic, had only one kind of theca and may have been hermaphrodites. Dichograptids flourished in the early Ordovician. Their stipes were few and arranged in various ways: e.g. stretched out sideways (horizontal), hanging down (pendant) or turned upwards (reclined). Tetragraptus had four horizontal or pendant stipes (a). Didymograptus had two pendant stipes (b). Isograptus had reclined stipes (and a long nema extending above the sicula) (c). © The British and Irish Graptolite Group (BIG G).

Diplograptids

Diplograptids evolved from dichograptids in the Ordovician. Orthograptus and Dicranograptus are from the Ordovician of southern Scotland.

a) The stipes of Orthograptus were fused ‘back-to-back’ (i.e. scandent).

b) Some later types of diplograptids became partly ‘unzipped’, like the Y-shaped Dicranograptus (the biserial part is 5 mm long).

c) Spirograptus turriculatus was coiled or spring-like

d) Rastrites had a curved stipe with long thecae up to 3 mm long

© The British and Irish Graptolite Group (BIG G).

Monograptids

One-stiped monograptids appeared at the beginning of the Silurian and evolved rapidly into many coiled, curved and straight species, with elongate, hooked or lobed thecae. Spirograptus turriculatus, Rastrites and Monograptus lobiferus are from the Silurian (Llandovery).

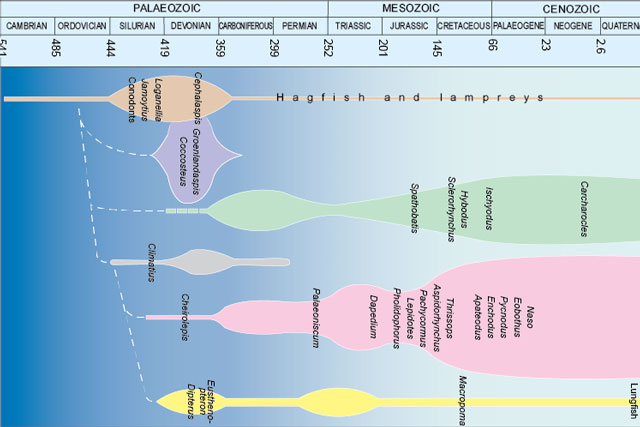

Graptolites through time

The history of graptolites (dendroids and graptoloids) and their diversity related to global events. The geological position of illustrated specimens are shown in italics. BGS © UKRI.

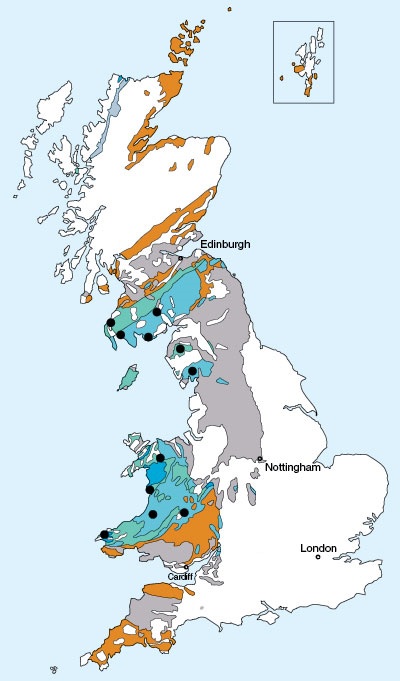

Graptolites in Britain

Graptolites are found only in Palaeozoic rocks such as those in Scotland, Wales and north-western England. The oldest dendroids occur in middle Cambrian rocks, but they can be found in rocks as young as the Carboniferous. Planktonic graptolites are particularly common in Ordovician and Silurian shales and mudstones.

Palaeozoic rocks of the UK and some good places to look for graptolites (see black spots). The colour code for geological periods is the same as for the history diagram. BGS © UKRI.

Fun facts

Graptolites are thought to have been hermaphroditic, with both male and female sexual organs on one single zooid. To avoid self-fertilisation, or inbreeding, zooids could have had the potential to be temporarily male, female or neuter. Zooids maturing at the near end of a colony might initially have been males whilst those occupying the larger, distal thecae may have manifested the female phase. But nobody knows for sure!

3D fossil models

![Orthograptus truncatus var. corrisensis. (SM A 10007 – Holotype). Ashgill Series (Ordovician Period) (443.8 – 449 Ma B.P.) [Closest ICS interval: Late Ordovician Epoch]. See 3D fossils online. GB3D Type Fossils.](https://www.bgs.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/P867340_1332x690-960x497.jpg)

Orthograptus truncatus var. corrisensis Davies. (Ordovician, Ashgill.) See 3D fossils online. GB3D Type Fossils. BGS © UKRI.

Many of the fossils in the BGS palaeontology collections are available to view and download as 3D models. To view this fossil, or others like it, in 3D visit GB3D Type Fossils.

Reference

Wilkinson, I P, Rigby, S, and Zalasiewicz, J A. 2001. Graptolites: fossil focus. (Nottingham, UK: British Geological Survey.)

You may also be interested in

Discovering Geology

Discovering Geology introduces a range of geoscience topics to school-age students and learners of all ages.

Fossils and geological time

Take a look at the history of the Earth, from its formation over four and a half billion years ago to present times.