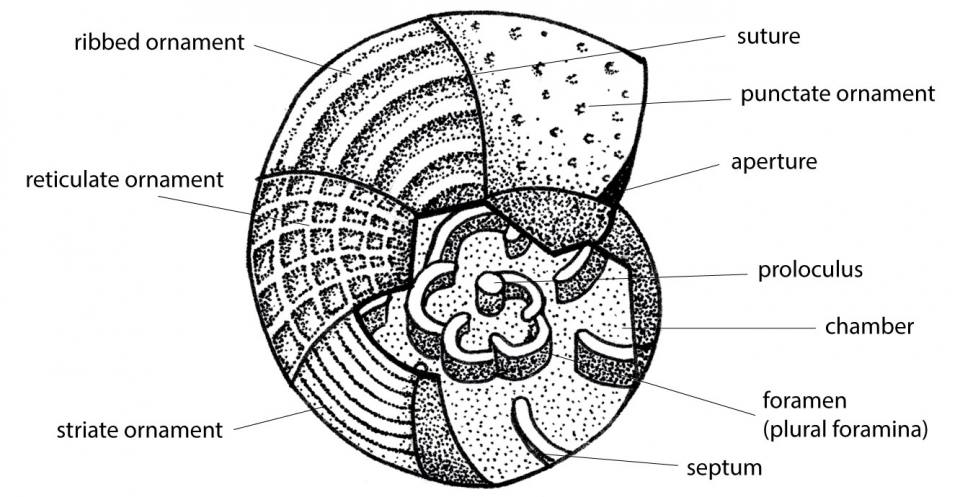

Foraminifera are amoeba-like, single-celled protists (very simple micro-organisms). They have been called ‘armoured amoebae’ because they secrete a tiny shell (or ‘test’) usually between about a half and one millimetre long. They get their name from the foramen, an opening or tube that interconnects all the chambers of the test. Fossilised tests are found in sediments as old as the earliest Cambrian (about 545 million years ago) and foraminifera can still be found in abundance today, living in marine and brackish waters.

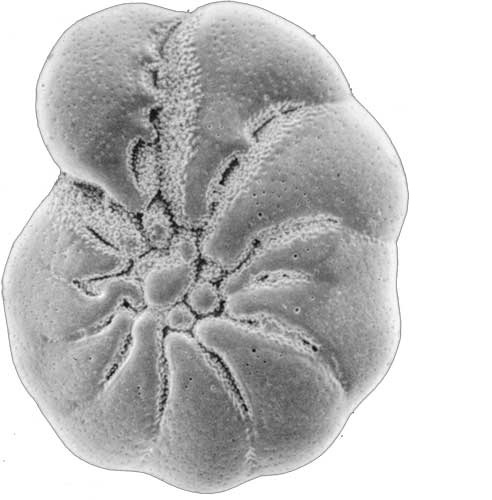

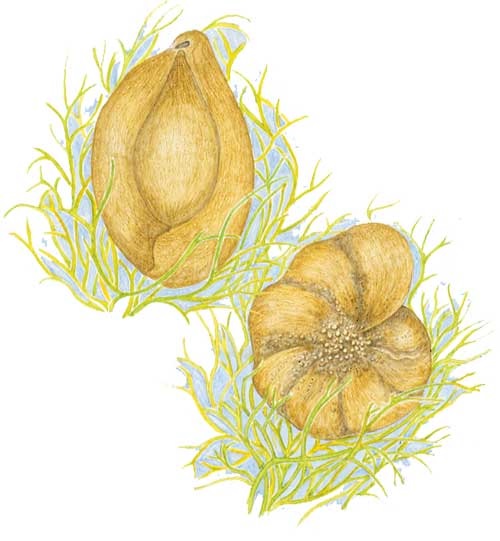

Elphidium liodense (Cushman) from the Quaternary of the Dovey Estuary, Wales. BGS © UKRI.

Biology

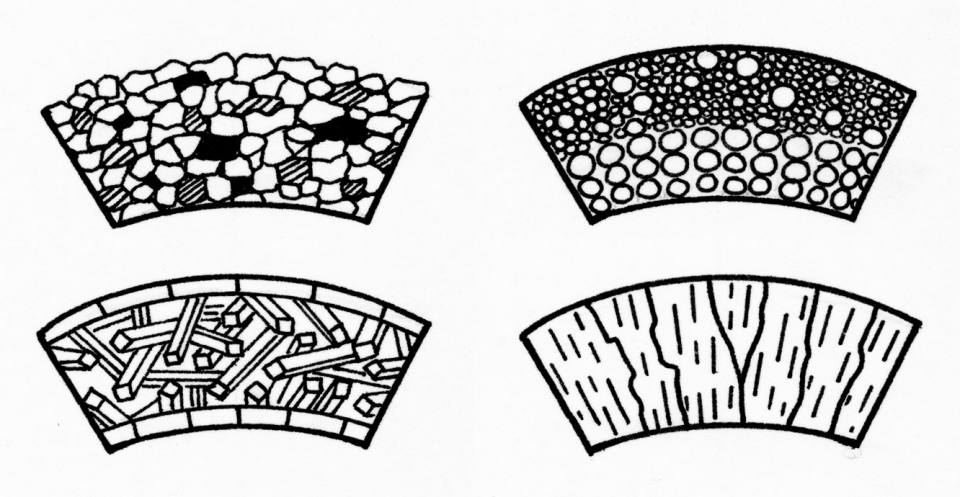

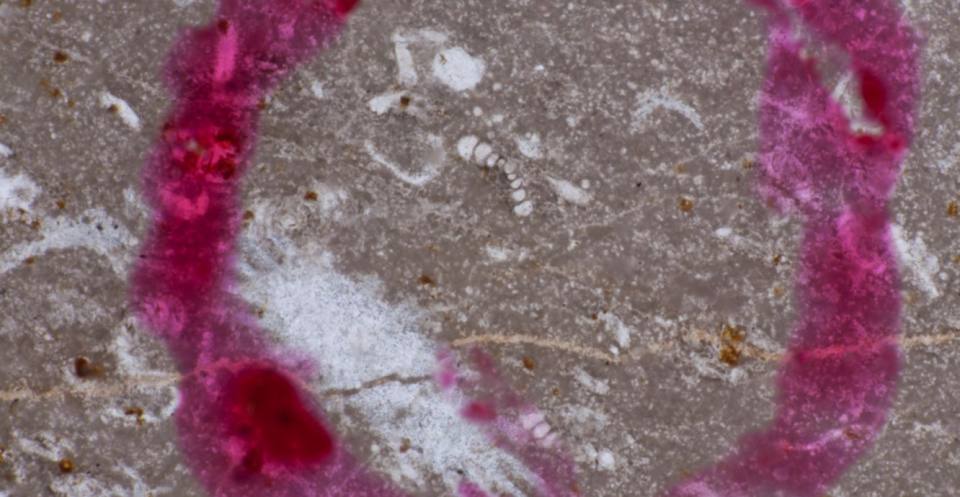

The tests of many foraminfera are made of aragonite or calcite, when the shell may be milky white (porcelaneous taxa), grey (microgranular taxa) or glassy (hyaline taxa). The tests of forminifera called allogromiids is made out of tectin, which is a soft and flexible organic material. Other foraminiferal tests are composed of organic matter, together with agglutinated particles of sand, silt or occasionally echinoid spines, radiolaria (protists with tests made of silica) or diatoms (a type of algae) cemented together with calcite or silica.

Cross-sections of foraminiferal walls (highly magnified) showing the different structures.

Top left: agglutinated wall made of cemented sand grains (textulariids); top right: microgranular wall made of granular calcite crystals (fusulinids); bottom left: porcelaneous wall made of three layers of calcite (miliolids); bottom right: hyaline wall made of calcite or aragonite crystals (rotaliids and robertinids). BGS © UKRI.

Types of test

The test, which is the part that is preserved as a fossil, can take many different shapes.

Simple tests

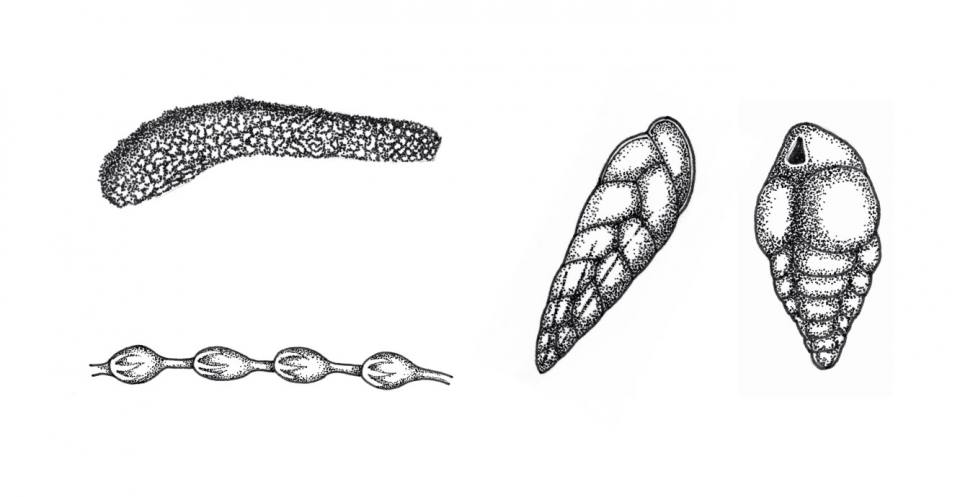

In some types of foraminifera, the chambers are added in a spiral and take a number of forms. The simplest is a sphere or a tube with an aperture (an opening) at one end: these are known as tubular. Chambers may be added in a single row, like a string of beads (uniserial). Those with two rows of chambers are called biserial and those with three rows, triserial.

Examples of simple tests.

Top left: tubular Rhizammina; bottom left: uniserial Nodosaria; centre: biserial Loxostomum; right: triserial Bulimina. BGS ©UKRI.

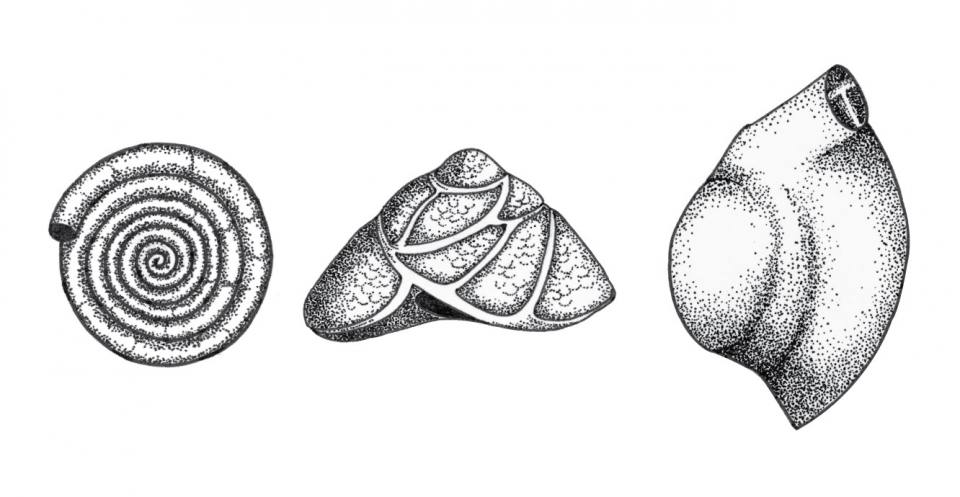

Spiral tests

In some types of foraminifera, the chambers are added in a spiral and take a number of forms. Planispiral tests look like a Catherine wheel whilst trochospiral tests are like a tiny snail. In streptospiral tests, each chamber is half a whorl.

Examples of spiral tests.

Left: planspiral Cornuspira; centre: trochospiral Asterigerinata; right: streptospiral Quinqueloculina. BGS © UKRI.

Complex tests

In some types of foraminifera the chambers are complex. Sometimes they can combine different test types.

Examples of complex tests.

Left: globular Lagena; right: globular and trochospiral Globigerina. BGS © UKRI.

Test formation

The last chamber of the test has one or more small openings called apertures. The proloculus is the first chamber of the test. It is small when the foraminifera has formed by sexual reproduction, but large when reproduction has been asexual.

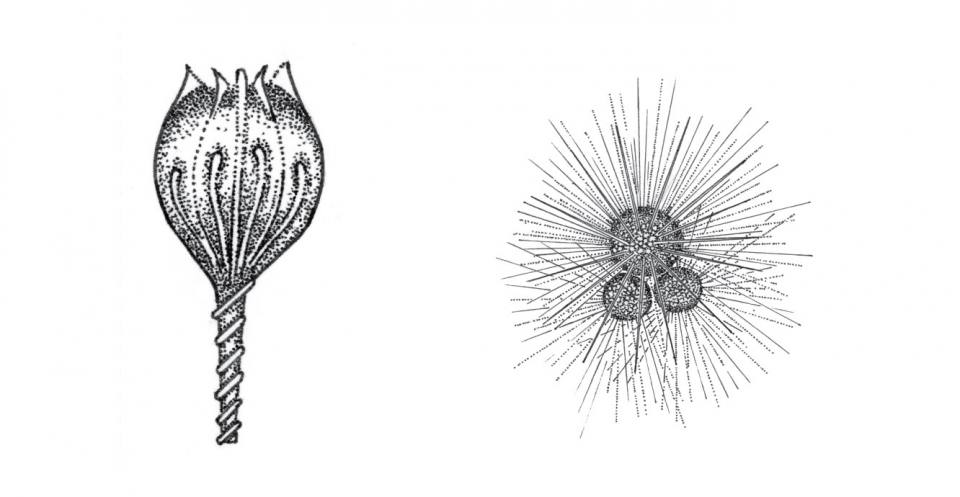

The living foraminifera

Protoplasm, the soft, jelly-like material that forms the living cell of a foraminifera, extrudes through the aperture to engulf the test of the living organism. The protoplasm on the outside of the test makes long filaments, which are used for locomotion and capturing food particles. Inside the test, the protoplasm is where the food is ingested and where the nucleus of the cell is found.

Foraminifera feed on diatoms, algae, bacteria and detritus.

Heterostegina depressa during chamber formation. Note the protoplasm extruded into long filaments. © R Rottger.

Environment

The most important factors that control living foraminifera are salinity and temperature, but other things like the substrate (weed, rock, silt, mud, sand, etc.), the amount of light and the amount of oxygen dissolved in the water are important.

Many foraminifera that live in river estuaries and coastal waters are hyaline (e.g. Elphidium) or agglutinated types. In shelf seas, the porcelaneous species (such as Quinqueloculina) become more numerous. In the deep seas, agglutinated forms predominate, mixed with the dead tests of planktonic species (e.g. Globigerina) that live near the surface of the ocean waters and rain down to the ocean floor on death.

Foraminifera that lived in the geological past were also controlled by the environment. Fossil foraminifera can be used to identify the conditions in which the enclosing sediments accumulated. We can use them to recognise, for example:

- glacial and warm episodes during the Quaternary

- changes in salinity in the Cretaceous

- variations in the oxygen content of the water in the Jurassic

- sea level oscillations during the Carboniferous

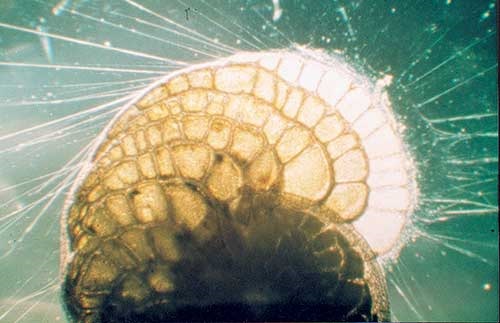

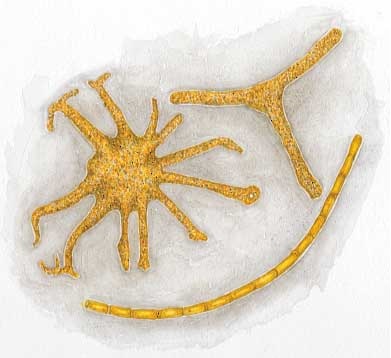

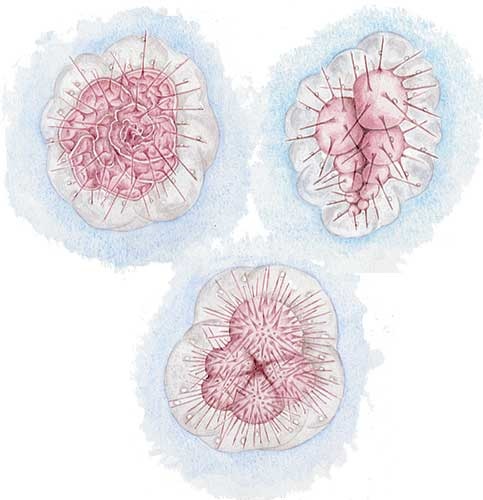

These are foraminifera from different geological periods, as if seen down a microscope. All are between 0.5 and 1 mm long except the abyssal species that can grow up to several centimetres.

Present day, agglutinated foraminifera live on the abyssal sea floor (4000 m deep). Bottom: Bathysiphon; left: Astorhiza; right: Rhabdammina. BGS © UKRI.

In the Quaternary, the miliolid Quinqueloculina (left) and rotaliid Elphidium (right) lived on weeds in Arctic, shallow-marine waters. BGS © UKRI.

Uvigerina (left), Gryoidinoides (centre) and Cibicidoides (right) lived in bathyal waters in the Palaeogene. BGS © UKRI.

Planktonic foraminifera lived in the photic zone (less than 200 m deep), near the ocean surface, during the late Cretaceous. Left: Globotruncana; bottom: Globigerinelloides; right: Heterohelix. BGS © UKRI.

Early Jurassic, hyaline Marginulina (left) and Frondicularia (right) lived in the shallow-marine waters of the continental shelf. BGS © UKRI.

Late Carboniferous, agglutinated Ammodiscus (top) and Ammovertella (bottom) lived in brackish, estuarine water. BGS © UKRI.

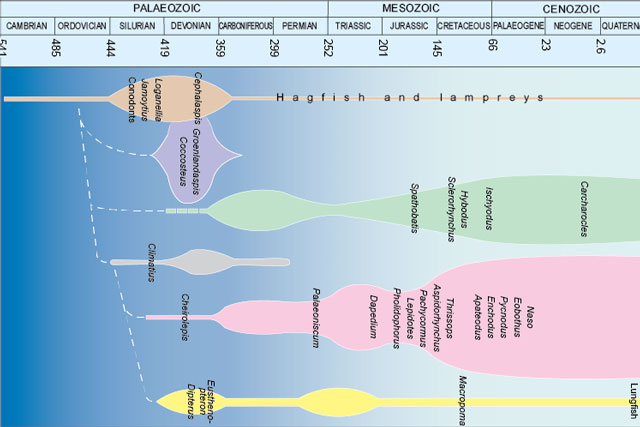

The geologists’ tool

The stratigraphical range of some foraminiferal species is very short and they can be used to give a relative age to the rocks in which they are found. The rocks can be assigned to foraminifera zones, which equate with periods of time. Zones may vary in length from a few thousand to several million years. They allow correlation of geographically separate rocks, which is very important when making geological maps, exploring for oil or gas and building large civil engineering projects.

- More information about foraminifera evolution

Myths and legends

Foraminifera were first discovered about 2000 years ago! The pyramids in Gizeh, Egypt, are in part built out of a Palaeogene limestone which contains huge numbers of Nummulites gizehensis, a large foraminifera that grew to several centimetres across.

Strabo (64 BC to AD 25), who came from Asia Minor but lived most of his life in Greece, wrote about these fossils, although he did not realise what they were.

There are heaps of stone chips lying in front of the pyramids and among them are found chips that are like lentils both in form and size; and under some of the heaps lie winnowings, as it were, of half-peeled grains. They say that what was left of the food of the workment has petrified and this is not improbable.

Strabo 17.1.34

Nummulites gizehensis, Strabro’s ‘lentil’: this magnified example is 2.8 cm in diameter but only 2 mm thick. BGS © UKRI.

3D fossil models

Spirillina groomii Chapman. (Triassic, Rhaetian). BGS © UKRI.

Many of the fossils in the BGS palaeontology collections are available to view and download as 3D models. To view this fossil, or others like it, in 3D visit GB3D Type Fossils.

Reference

Wilkinson, I P. 1997. Foraminifera: fossil focus. (Nottingham, UK: British Geological Survey.)

You may also be interested in

Discovering Geology

Discovering Geology introduces a range of geoscience topics to school-age students and learners of all ages.

Fossils and geological time

Take a look at the history of the Earth, from its formation over four and a half billion years ago to present times.