Fish are cold-blooded creatures that inhabit all kinds of water bodies, from small ponds to the deep sea. They are vertebrates, with a backbone made of cartilage or bone and a brain case protecting the brain. They swim using fins and take oxygen from the water by means of gills (although some also have lungs).

These features distinguish them from:

- invertebrates such as sea urchins, molluscs and crabs

- amphibians and reptiles, which have lungs and limbs rather than gills and fins

- whales and dolphins, which are warm-blooded mammals with lungs

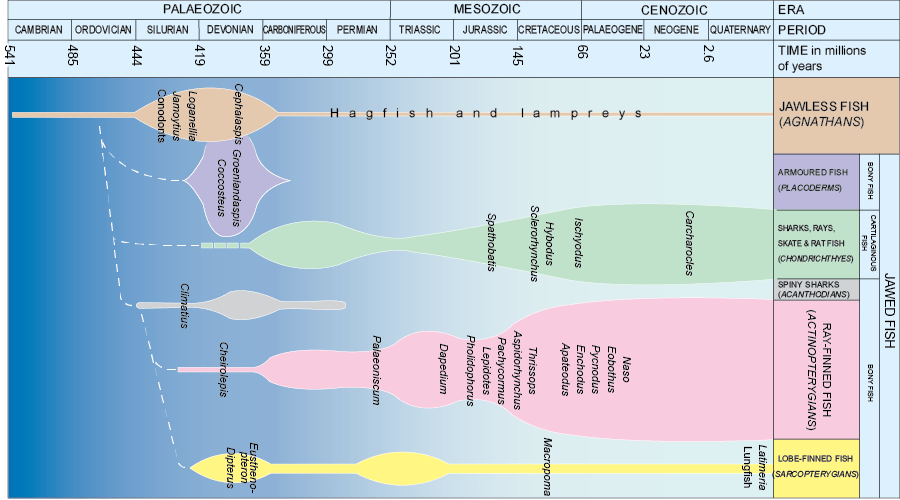

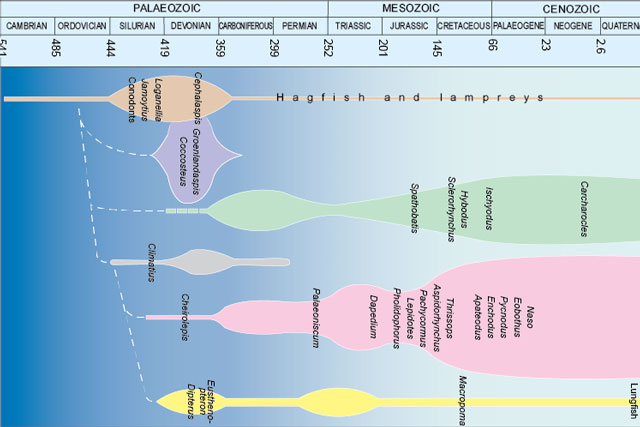

Since the late Cambrian, fish have evolved into thousands of species and today they form over half of all living vertebrates.

Dapedium, a mollusc-eating, ray-finned fish that lived in Dorset during the early Jurassic. BGS © UKRI.

Fish through time

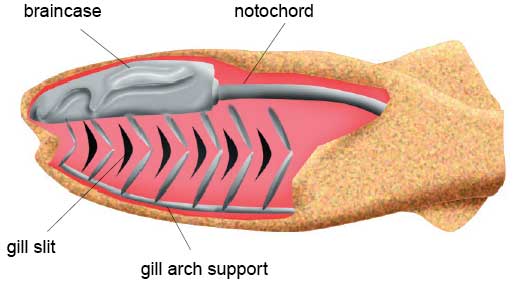

The origin of fish is obscure, but may be found in something like the invertebrate sea squirts or echinoderms. The nearest ancestor to the fish may have been the chordate, Pikaia, which inhabited deep marine waters during the Cambrian. It lacked bones and jaws, but had a notochord (a primitive ‘back bone’ made of cartilage) on which were attached muscles used for swimming.

Here, we look at the main fish groups and outline their evolution through geological time.

Jawless fish, which resemble living lampreys, first appeared in the early Cambrian and later evolved into many types, including Loganellia and Jamoytius. Some (e.g. Cephalaspis) were protected by thick scales or by a bony head shield. None had bones within their bodies (although they had a notochord, a primitive cartilaginous backbone) and so fossils are rare.

One group, the conodonts, were for decades known only from teeth found in Palaeozoic rocks, but very rare fossils of their soft, eel-like body have now been found.

Jawless fish ate tiny organisms and food particles from the sea floor and some may have sucked blood.

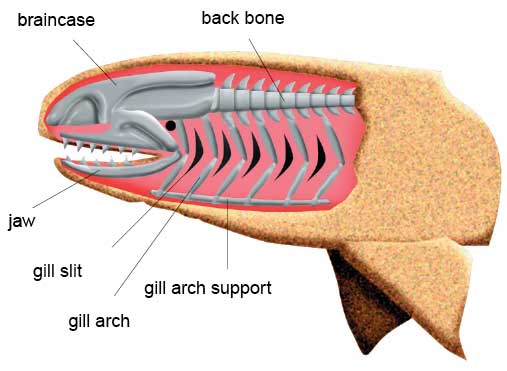

The development of jaws and teeth resulted in changes in diet — fish no longer had to eat small food particles, but could catch larger prey. Many different types of jawed fish evolved, but they can all be put in two large groups:

- those with a cartilaginous skeleton (chondrichthyes)

- those with a bony skeleton (osteichthyes):

- placoderms (the earliest of all jawed fish)

- acanthodians

- ray-finned and lobe-finned fish

Chondrichthyians (cartilaginous fish) such as sharks, rat fish, rays and skates (e.g. Hybodus, Ischyodus, Spathobatis and Sclerorhynchus) had skeletons made of cartilage. The use of cartilage rather than bone was once thought to be a primitive feature, but it is now believed to be an evolutionary advance to aid buoyancy.

The most primitive bony fish were the placoderms. They had a bony skeleton, an ‘armoured’ head shield and plates that covered the front part of their body (e.g. Groenlandaspis and Coccosteus).

‘Spiny sharks’ (acanthodians), such as Climatius, had a cartilaginous skeleton covered by a thin film of bone. Some were marine and others lived in fresh water. These two groups formed short-lived lineages prior to the evolution of the more successful ray-finned and lobe-finned fish.

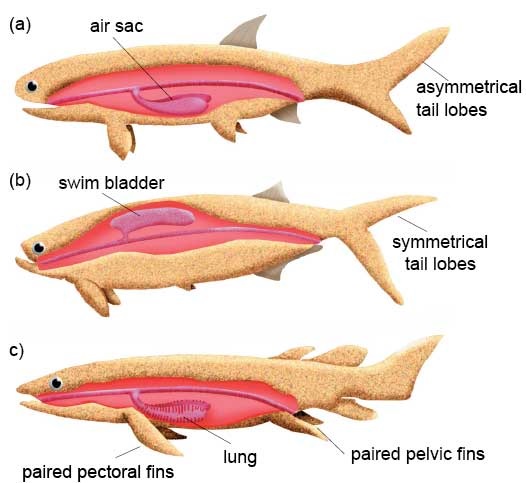

Lobe-finned fish, which include coelacanths (e.g. Macropoma) and lungfish (such as Dipterus), first evolved during the late Silurian. They had a bony skeleton and scales like the ray-finned fish, but the paired pectoral and pelvic fins were long muscular lobes, with a bony skeleton and rays, that could be moved independently by muscles. Lungfish are still found living in parts of Brazil, western Africa and eastern Australia and coelacanths live off southern Africa and Indonesia.

The evolution of the lobe-finned fish was one of the most important steps in the evolution of vertebrates. Comparison with modern fish suggests that the pair of air sacs of primitive bony fish developed into the swim bladder of many ray-finned fish, but lungs in the lobe-finned fish. The lobed fins of Eusthenopteron evolved into legs and the early amphibians (e.g. Ichthyostega) developed.

Ray-finned fish get their name from the bony rays that support and stiffen the fins, but which lack muscles — all movement was controlled by muscles in the body. The fins of the most primitive, like Cheirolepis, were rigid, but gradually they evolved, through a stage of slight flexibility, into the mobile fins of today’s modern fish.

Evolution brought other refinements. The air sacs of primitive types developed into swim bladders that control buoyancy. The heavy ‘armour’ was replaced, first by thick, bony scales (e.g. Palaeoniscum) and then by light flexible scales (e.g. Naso). The skeleton of the tail became symmetrical with lobes of equal length, like in Pholidophorus, giving strong propulsion and improved mobility.

Ray-finned fish inhabited both fresh water environments and the sea. Many different types evolved, including the teleosts, the group that forms most of the fish of today. These have thin scales, symmetrical tails and very mobile jaws and fins. One of the earliest teleosts was the herring-like Pholidophorus, which had heavy, enamelled scales and only a partially ossified ‘backbone’. Salmon-like Enchodus had thin scales and an entirely bony skeleton. Later on, trout, cod, haddock and perch-like fish appeared.

The evolution of the main groups of fish through geological time. The names of those fish illustrated or mentioned in the text are in italics to show their relative age. BGS © UKRI.

Myths and legends

Tongue stones

Pliny the Elder, a Roman scientist who lived from AD 23 to AD 79, wrote about ‘tongue stones’. He said they resemble a man’s tongue and were thought to have fallen from heaven during lunar eclipses.

In reality, ‘tongue stones’ are the teeth of fossil sharks like Carcharocles. It was believed that they had medicinal properties preventing rheumatism and, if placed in wine, they formed an antidote against snake venom. This latter notion probably comes from a legend that St Paul was bitten by an adder when he was shipwrecked on the island of Malta. It was said that he turned the tongues of all the snakes to stone so that they were no longer venomous. Some people still carry a ‘tongue stone’ as a talisman against bad luck.

A Carcharocles tooth from the Neogene of England. BGS © UKRI.

Toad stones

In his play As You Like It, William Shakespeare referred to the belief that ‘toad stones’ formed inside the head of a toad. If they were removed while the toad still lived, they were believed to have magical powers and so were often put into rings or pendants. When ground into powder toad stones were said to have medicinal properties as an antidote to poison and a treatment for epilepsy.

In reality, toad stones were usually the teeth of the fossil fish Lepidotes.

The source of toad stones, Lepidotes, from the Jurassic/Cretaceous boundary interval, near Swanage, Dorset. BGS © UKRI.

3D fossil models

Pinnalongus saxoni. (Devonian, Eifelian.) BGS © UKRI.

Many of the fossils in the BGS palaeontology collections are available to view and download as 3D models. To view this fossil, or others like it, in 3D visit GB3D Type Fossils.

Reference

Wilkinson, I P, and Young, S. 2000. Fish: fossil focus. (Nottingham, UK: British Geological Survey.)

You may also be interested in

Discovering Geology

Discovering Geology introduces a range of geoscience topics to school-age students and learners of all ages.

Fossils and geological time

Take a look at the history of the Earth, from its formation over four and a half billion years ago to present times.