Shale is a fine-grained, sedimentary rock formed as a result of the compaction of clay, silt, mud and organic matter over time and is usually considered equivalent to mudstone. Shales were deposited in ancient seas, river deltas, lakes and lagoons and are one of the most abundant sedimentary rock types, found at both the Earth’s surface and deep underground.

Shale gas is natural gas found in shale deposits, where it is trapped in microscopic or submicroscopic pores. This natural gas is a mixture of naturally occurring hydrocarbon gases produced from the decomposition of organic matter (plant and animal remains). Typically, shale gas consists of 70 to 90 per cent methane (CH4), the main hydrocarbon target for exploration companies. This is the gas used for generating electricity and for domestic heating and cooking.

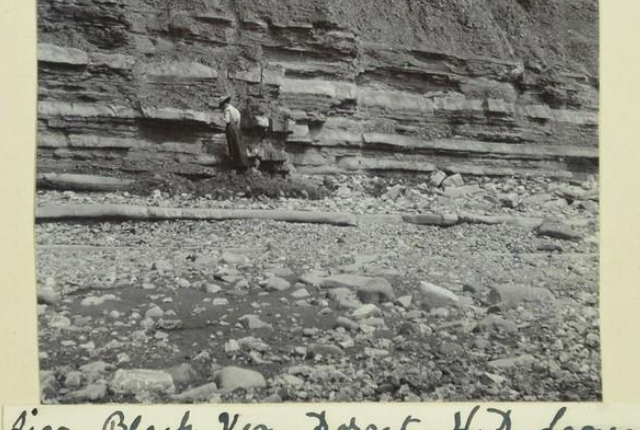

Interbedded dark mudstone and dolomitic and calcareous mudstone/siltstone of the Upper Bowland Shale Formation. BGS © UKRI.

How is shale gas different from conventional gas?

Hydrocarbons, such as oil and gas, are produced by the transformation of organic matter (plants; animals; algae, etc.) as a result of increased temperature and pressure. This occurs when a potential source rock, rich in organic matter, is buried and heated at considerable depth (usually thousands of metres below the surface).

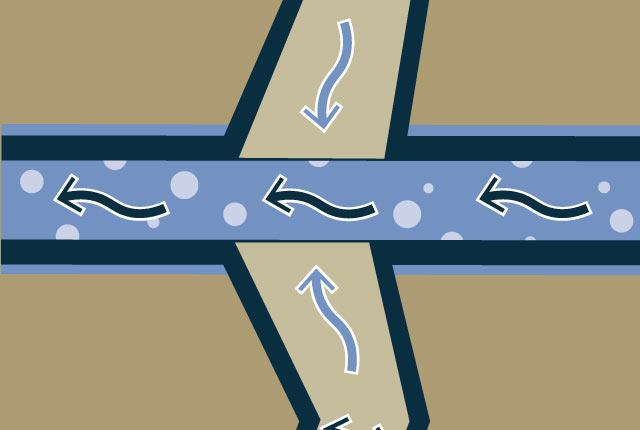

The hydrocarbons migrate upwards where they may find their way into porous reservoir rocks, typically a sandstone or a porous limestone. If the reservoir rock is overlain by an impermeable cap or seal rock, such as one rich in clay, the hydrocarbons become trapped in the reservoir rock. Conventional hydrocarbons can be extracted by drilling directly into the reservoir rock.

Shale gas is a form of unconventional hydrocarbons because the rock it is extracted from acts as the source, reservoir and cap rock. The gas is produced, stored and sealed within impermeable shale and can be released only after the shale is drilled and artificially fractured during an extraction process.

Our role and research

The BGS’s role is to provide independent, expert and impartial geological and environmental advice to industry, government and the public, regarding shale gas in the UK.

We research all aspects relevant to shale gas in the UK and internationally. Our research spans from resource estimation to the environmental impacts associated with shale gas extraction, such as investigating groundwater contamination and microseismicity.

Whilst shale gas extraction is not presently permitted in the UK, we continue to conduct research related to shale gas. We actively publish reports and academic papers on a variety of topics related to shale gas.

In this section

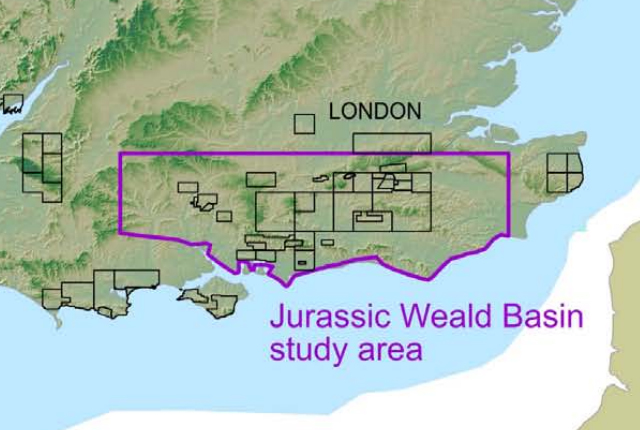

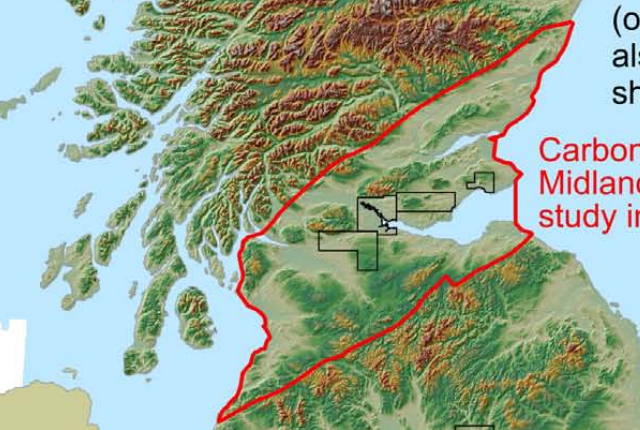

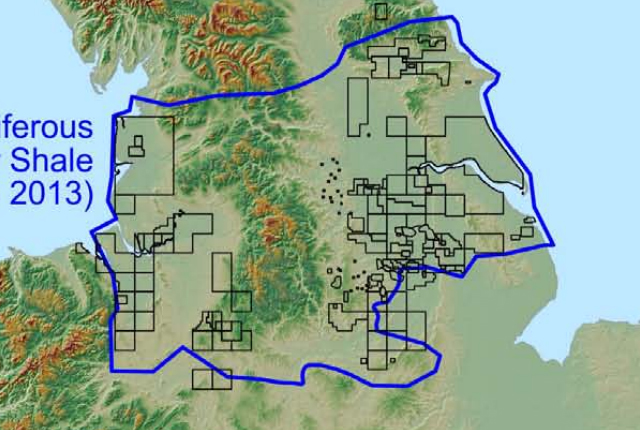

Shale gas in the UK

The UK has a number of sites that have been explored for shale gas deposits.

Shale gas extraction

Shale gas is extracted from microscopic pores in impermeable shale rock through a process called hydraulic fracturing.

BGS shale gas research

We provide independent, expert and impartial geological and environmental advice with continued monitoring and publication of the latest data.