Why do we store geological core?

With space at a premium and the advance of new digitisation techniques, why does retaining over 600 km of physical specimens remain of national importance?

11/09/2025 By BGS Press

In a warehouse just outside Nottingham, vast racks of geological core are carefully curated and stored in climate-controlled conditions. Part of the collections held within BGS’s National Geological Repository (NGR), this core is quietly energising the UK’s economy, supporting the nation’s growth agenda and energy transition aspirations.

Understanding our subsurface environment requires both direct observation, through samples such as drill core, and indirect observation, through sensors and monitoring. These observations are the basis on which we build models that constrain and test hypotheses explaining the Earth, its composition and its many processes. Such knowledge is critical for determining how society is affected by or can safely interact with the ground beneath our feet.

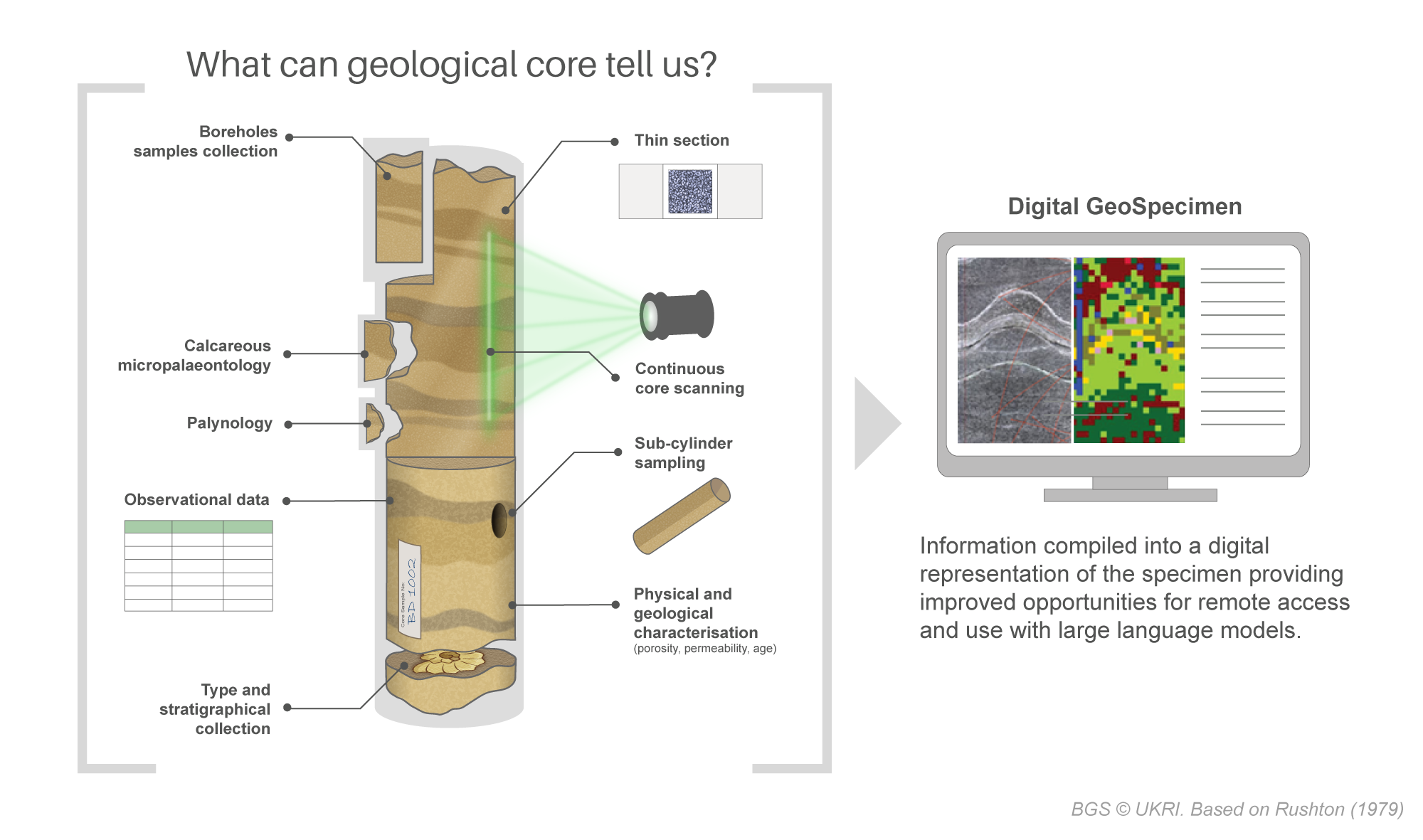

What can geological core tell us? BGS © UKRI. Based on Rushton (1979).

Saving cost, reducing risk and accelerating project timelines

Drilling new core is expensive. The cost of drilling just one new offshore borehole can be in the region of £20 to £30 million, around 20 times more than the annual operational costs for the NGR. Access to existing core can therefore significantly streamline the process for new infrastructure projects; it allows both public and private sector project managers to plan with a greater degree of certainty and better mitigate risk. More informed planning can result in drilling fewer new boreholes and a shorter project timeline. This not only saves significant costs; it also reduces any associated environmental impact.

Digital scanning has unlocked new opportunities … with limitations

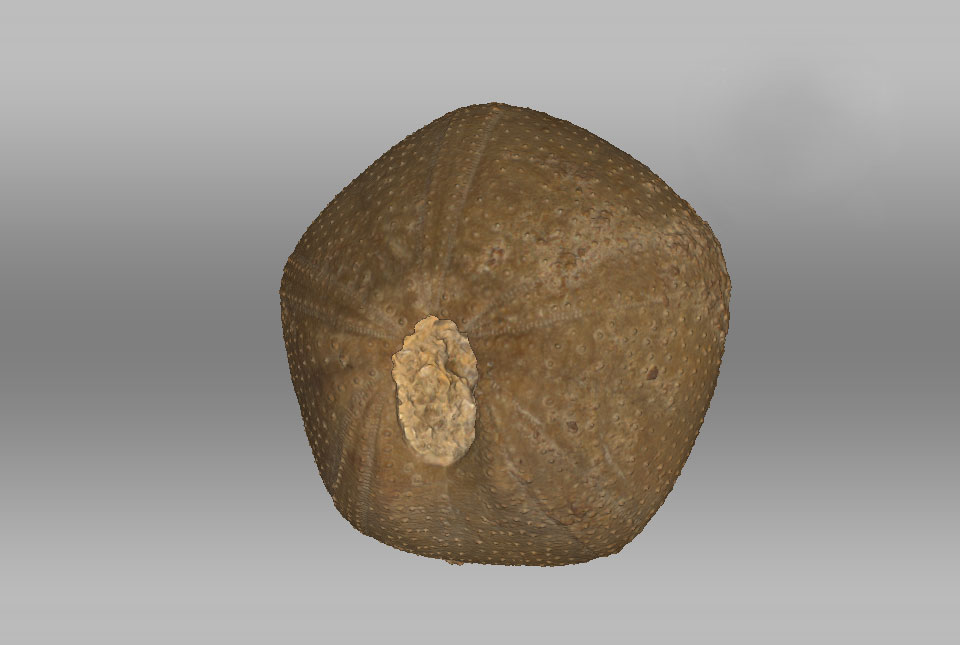

Digitisation of rock samples and core is a powerful tool for the modern-day geologist. Improvements in analytical techniques, including core scanning and 3D imagery, allow cores to be re-studied and preserve a record of the original material prior to sampling. These advancements are providing scientists with better opportunities to investigate changes in physical properties such as porosity (the free space inside a rock that fills with fluids).

An array of scanning technologies, including X-rays and hyperspectral imaging, allows scientists to extract more data than ever before from samples. Collectively, this data, sourced from different analytical techniques, can be compiled into digital geo-specimens that enable exciting opportunities through machine learning and artificial intelligence tools. However, there is a cost associated with scanning and digitisation. With the size of the core archive, these activities need to be targeted to deliver the largest benefit to the UK.

Scanned geological core from the Glasgow UK Geoenergy Observatory – GGC01 borehole drilled into Scottish coal measure. BGS © UKRI 2025

Although geological observations and digital samples have significant long-term value, they are limited by the context in which they were collected and the technologies available at the time. Discarding physical samples after digitising risks losing the ability to re-examine them with new techniques and technologies as they emerge in future. Digitisation enhances the samples, makes them more discoverable, and increases their value, but is not a replacement for holding physical specimens.

Safeguarding for the future

What society needs from the subsurface changes over time. The academic and commercial relevance of core varies and does so in ways that can be hard to predict. Many of the reservoir cores from the Southern North Sea gas fields, which were drilled in the 1960s and 1970s, are now being re-studied to assess their potential for carbon dioxidestorage. Sites that were once prized for their coal reserves are now being revisited for geothermal potential. These uses were almost certainly never envisaged when the core was originally drilled.

In some cases, the core may be unique and irreplaceable, especially where land has since been developed or reclassified (for example, as a Site of Special Scientific Interest). Maintaining a reference library of boreholes enables future research to take place using new techniques, saving time, reducing costs and limiting the environmental impact. Crucially, it also supports reproducible and repeatable science.

Physical space within the NGR is always a consideration. It is not possible to retain every specimen we are offered. Material is selected based on its value to inform the geological record. Sometimes, materials may be discounted or discarded where there is an abundance of material from a particular area or where samples have deteriorated, but such instances are rare. BGS is actively exploring funding opportunities to expand this national facility, so that we can continue to ingest materials critical to the UK economy.

Over the last two decades, it is estimated that the NGR has saved the UK economy at least £1.5 billion in avoided drilling and analysis costs alone. The importance of this facility can only increase as we maximise the potential of geological ‘super regions’ for renewable energy technologies.

As demand for natural resources grows and the effects of climate change intensify, so does the need for geological data to address the economic and societal challenges. All indications are that the most important phase of the NGR is yet to come.

Rushton, A W A. 1979. The fossil collections of the Institute of Geological Sciences. 57-66 in

Curation of Palaeontological Collections: a joint colloquium of the Palaeontological Association and Geological Curators’ Group, Vol. 22. Bassett, M G (editor). (Dyfed, UK: Palaeontological Association.)

Relative topics

Related news

Scientists gain access to ‘once in a lifetime’ core from Great Glen Fault

01/12/2025

The geological core provides a cross-section through the UK’s largest fault zone, offering a rare insight into the formation of the Scottish Highlands.

Why do we store geological core?

11/09/2025

With space at a premium and the advance of new digitisation techniques, why does retaining over 600 km of physical specimens remain of national importance?

New study reveals geological facility’s value to UK economy

19/08/2025

For the first time, an economic valuation report has brought into focus the scale of the National Geological Repository’s impact on major infrastructure projects.

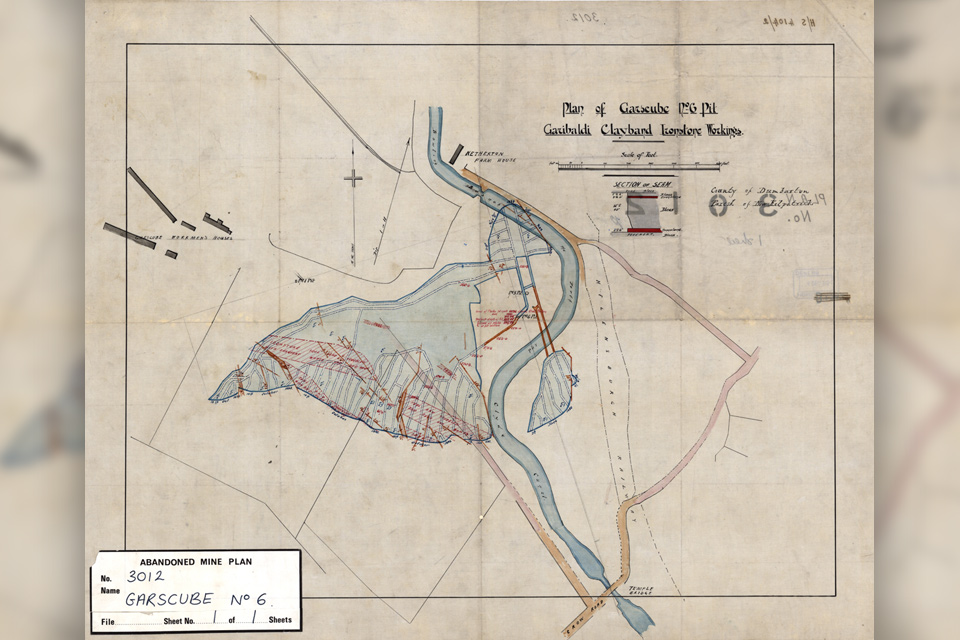

Release of over 500 Scottish abandoned-mine plans

24/06/2025

The historical plans cover non-coal mines that were abandoned pre-1980 and are available through BGS’s plans viewer.

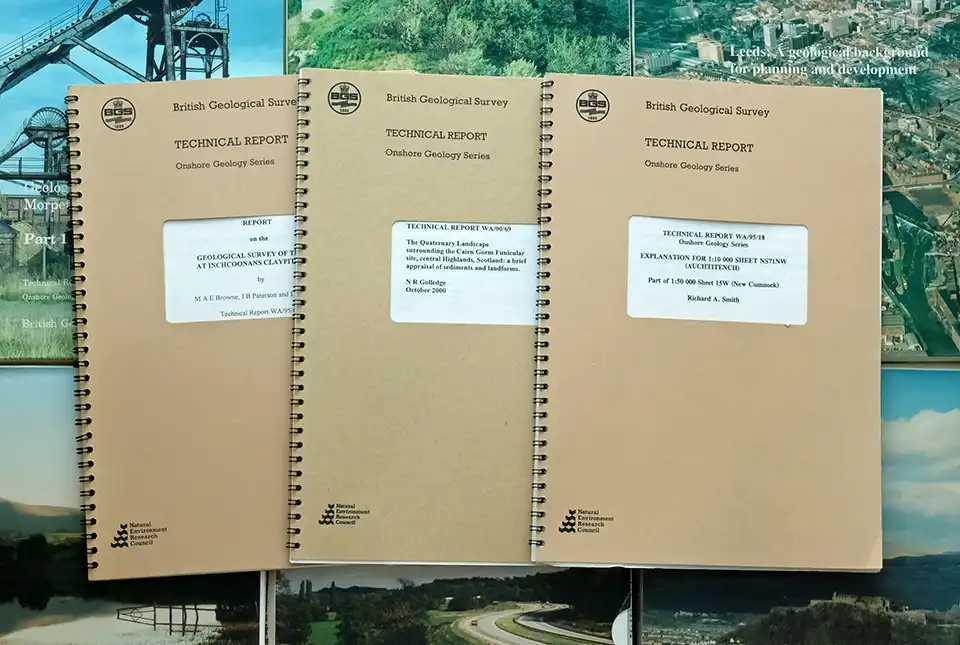

BGS’s National Geoscience Data Centre releases over 8000 technical reports

05/06/2024

The technical reports, covering the full spectrum of BGS activities and subjects, were produced between 1950 and 2000.

The art of boreholes: Essex artists visit the BGS to be inspired by our library of geological core

02/11/2023

Two UK-based artists visitors aim to turn art and earth science into a collaborative experience that facilitates discussion on land usage.

Boreholes aren’t boring!

31/07/2023

Work experience student Patrick visited BGS to learn more about being a professional rock lover.

Mineral investigation reports released online

07/07/2023

Reports from over 260 mineral exploration projects are now freely available on BGS’s GeoIndex.

Core Store solar project supports BGS net zero targets

02/07/2021

A large new solar panel array on the roof of the BGS Core Store is expected to result in a significant reduction in our carbon footprint.