The Stone of Destiny

The origins of the Stone of Scone: where it came from, why BGS has crumbs of it in its collections and the little-known fact that it is upside down.

03/05/2023

History of the stone

The Stone of Scone (pronounced ‘skoon’), also known as the Stone of Destiny or, in England, the Coronation Stone, is a slab of sandstone upon which the monarchs of Scotland have been crowned since medieval times. Stories about its origin are shrouded in mystery; one says it is the Biblical Jacob’s Pillow; another has it being used by ancient tribes of Scots in County Antrim before being brought to Scotland and still another states it originally came from the Roman Antonine Wall.

What is known is that it was used as a crowning-seat for Scottish monarchs at Scone Palace in Perthshire between the 9th and 13th centuries, until it was stolen in 1296 by King Edward I of England, the ‘Hammer of the Scots’. He took the stone to Westminster in London and had it mounted in a wooden throne; since then, English monarchs would be crowned above the stone as a symbol of the dominion they claimed to have over Scotland. It was not returned to its homeland until 1996, where it now resides in Edinburgh Castle.

The Stone of Scone at BGS

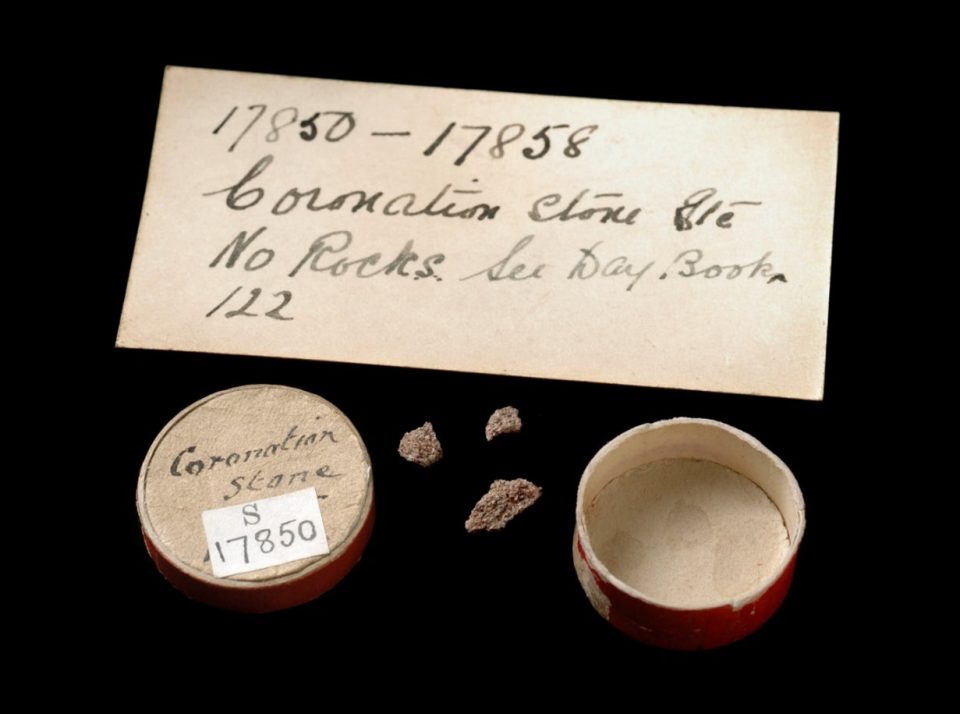

The stories and myths around the Stone of Scone are well known, but what is less well known is that fact that BGS has a sample of it as part of its Scottish collections. According to BGS’s records, the sample was collected in the late 19th century by either Sir A C Ramsay or Sir J J H Teall, both of whom later became directors of the Geological Survey of Great Britain (now the British Geological Survey).

The entry in BGS’s collections register corresponds to this sample and an additional six microscope slides, labelled S17850 to S17855, and refers to them rather irreverently as ‘crumbs from the Stone of Scone’. The entry for sample S17855 states that it was added to the collection by Teall, with the clear implication that this applies to the other thin sections and the rock chips. These microscope slides may, collectively, be samples collected by Ramsay in 1865 and were later registered by Teall as part of BGS’s Scottish collection. Ramsay examined the stone in Westminster Abbey and described how he took a sample by sweeping its lower surface with a soft brush, detaching as many grains ‘as would cover a sixpence’.

The grain mount thin sections made from Ramsay’s samples were later examined by another BGS geologist, C F Davidson, in 1937. Davidson stated that the ‘microscopic preparations’ were obtained in 1892. It is possible that he confused the year in which the samples were registered (possibly 1892) with that in which they were originally collected (1865). The additional loose rock chips may have been collected separately, perhaps in 1892 by Teall, and given the same sample number as one of the original microscope slides.

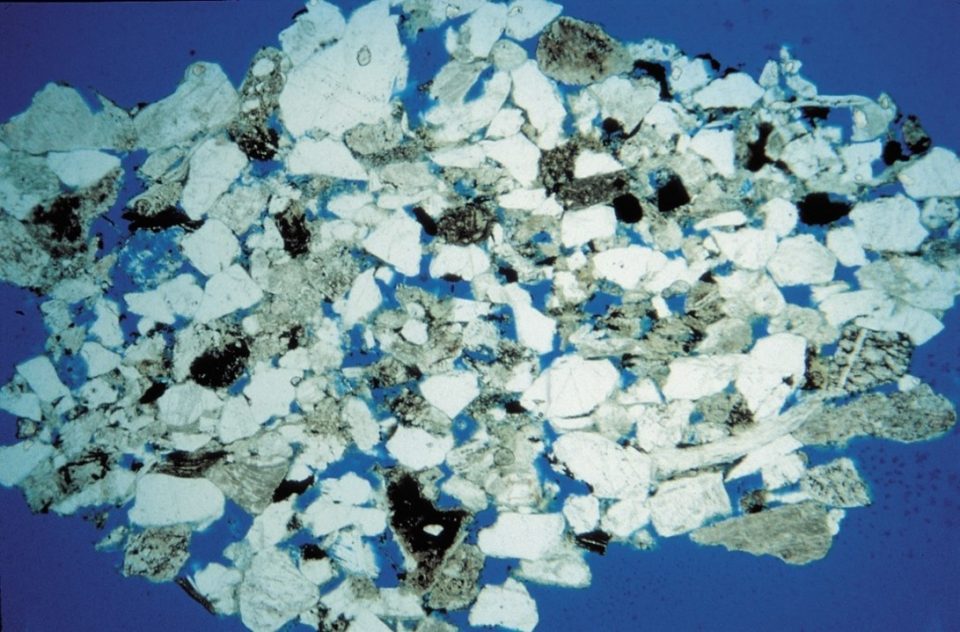

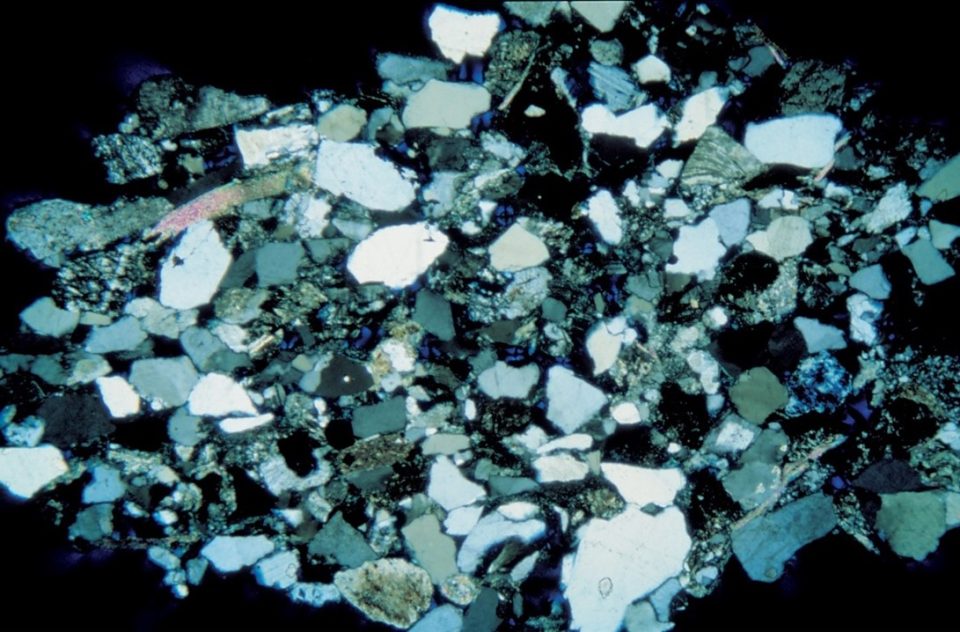

The samples held by BGS are of a pale-pink sandstone that is lithologically similar to the Stone of Scone. Detailed analysis of the microscope slides in 1998 and the actual stone on its return to Scotland confirmed that it resembles the Lower Devonian sandstones from the Perth area. In particular, the texture, mineral assemblage and colour are similar to the Devonian sandstones of the Scone Sandstone Formation that are exposed in the vicinity of Quarry Mill, near Scone Palace.

Is this the real Stone of Scone?

There has always been a question as to whether the stone now used in the coronation ceremony is the original, ‘real’ Stone of Scone. It was rumoured that the monks who guarded the stone at Scone Palace gave the English king a fake and that this is the stone that now sits in Edinburgh Castle. The stone was also stolen from Westminster Abbey in 1950 by a group of Scottish students, who hid it until 1951 when they handed themselves in and revealed the stone’s location. Rumours abounded again that they had returned a fake and that the real stone remains hidden away, adding another chapter to the stone’s mysterious history.

Is the Stone of Destiny upside down?

Examination of the Stone of Scone reveals that it is a single bed of cross-laminated sandstone. The cross-lamination was formed by sand waves moving across the bed of an ancient Devonian river that once flowed across central Scotland. The curved shapes of the sedimentary structures shows that the smooth, upper surface of the stone was the original base of the sandstone bed and the ‘base’ of the stone, which has been left uneven and unworked, is the irregular top of the sandstone bed. Geologically speaking, the Stone of Destiny is indeed ‘upside down’, possibly because the base of the sandstone bed was smoother and much easier for the original stone mason to work to provide the required flat surface.

The coronation of King Charles III

In May 2023 the Stone of Scone will once again travel south to Westminster, where it will be installed in the coronation chair that King Charles III will sit in when he is crowned in Westminster Abbey. After this it will return to Scotland once more to await the coronation of the next monarch of the United Kingdom.

About the authors

Welander, R, Breeze, D J, and Clancy, T O (editors). 2003. The Stone of Destiny: artefact and icon. Society of Antiquaries of Scotland Monograph Series, No. 22. (Edinburgh, UK: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.) ISBN: 978-0903903226

New UK/Chile partnership prioritises sustainable practices around critical raw materials

09/02/2026

BGS and Chile’s Servicio Nacional de Geología y Minería have signed a bilateral scientific partnership to support research into critical raw materials and sustainable practices.

Extensive freshened water confirmed beneath the ocean floor off the coast of New England for the first time

09/02/2026

BGS is part of the international team that has discovered the first detailed evidence of long-suspected, hidden, freshwater aquifers.

Hole-y c*@p! How bat excrement is sculpting Borneo’s hidden caves

23/12/2025

BGS researchers have delved into Borneo’s underworld to learn more about how guano deposited by bats and cave-dwelling birds is shaping the subsurface.

BGS awarded funding to support Malaysia’s climate resilience plan

17/12/2025

The project, funded by the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, will focus on minimising economic and social impacts from rainfall-induced landslides.

New geological maps of the Yorkshire Wolds to better inform groundwater management and policy decisions

17/12/2025

The new mapping provides crucial data on localised geological issues that may assist in protecting water supplies.

BGS agrees to establish collaboration framework with Ukrainian government

11/12/2025

The partnership will focus on joint research and data exchange opportunities with Ukrainian colleagues.

New 3D model to help mitigate groundwater flooding

08/12/2025

BGS has released a 3D geological model of Gateshead to enhance understanding of groundwater and improve the response to flooding.

New research shows artificial intelligence earthquake tools forecast aftershock risk in seconds

25/11/2025

Researchers from BGS and the universities of Edinburgh and Padua created the forecasting tools, which were trained on real earthquakes around the world.

New research highlights significant earthquake potential in Indonesia’s capital city

04/11/2025

Research reveals that a fault cutting through the subsurface of Jakarta could generate a damaging earthquake of high magnitude.

Fieldwork on Volcán de Fuego

13/10/2025

Understanding how one of the world’s most active volcanoes builds up material, and how they collapse to feed hot flows

PhD adventures in the Philippines: coring around Lake Bulusan

05/09/2025

Chris Bengt recounts his two-week field trip to Bulusan Volcano Natural Park in the Philippines to collect lake sediment cores, fresh soil and water samples.

New geological ‘pathways’ discovered beneath Welsh capital

02/09/2025

Scientists have discovered cavities in the clay underneath Cardiff, which will influence the siting of future geothermal developments.