Geochemistry and ‘sea elephants’

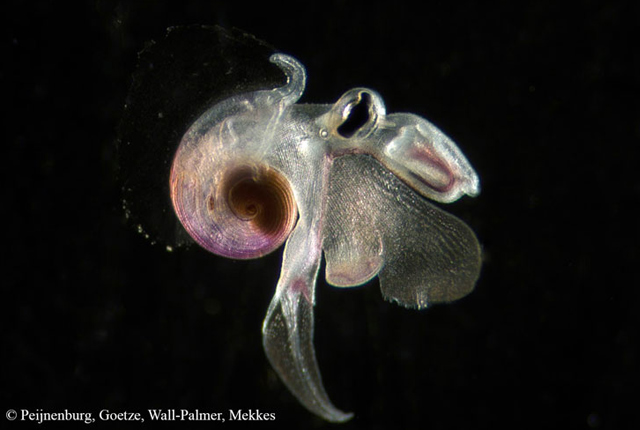

'Sea elephants' are very tiny swimming snails that are called elephants because they have a type of trunk.

02/11/2018 By BGS Press

Debbie Wall Palmer first stumbled across atlantid heteropods (very tiny, swimming snails that are rather oddly called a ‘sea elephant’ because they have a type of trunk) while looking for benthic foraminifera in Caribbean sediment samples, during her masters project at the University of Plymouth. It took her a long time to find out what these tiny, beautiful, delicately coiled shells were, because there are so few specialists working in this field. This little-known group of planktonic snails, which have a foot adapted for swimming and athetrunk that gives them their nickname, intrigued her.

After almost 10 years working on calcareous plankton, Debbie has the opportunity to continue researching atlantids as a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Research Fellow at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden, Netherlands.

Teaming up with BGS

Despite the current surge in research upon the aragonite-shelled pteropods and their response to ocean acidification, the atlantid heteropods, which also have an aragonite shell (an unstable form of calcite) and live in the upper ocean, have barely been considered. This is largely due to a lack of baseline data on diversity and distribution, and a lack of identification skills. So, in pursuit to find out fundamental information about the atlantids, Debbie teamed up with BGS’s Melanie Leng in the Stable Isotope Facility at BGS to answer the question ‘at what depth do atlantids live?’

Why do we need to know where atlantids live?

Understanding the vertical distribution of planktonic gastropods is essential when considering the effects of imminent ocean acidification and climate change. It has long been hypothesised that the atlantid heteropods reside in the upper 250 m of the ocean, but this is a very broad definition of their habitat. Previous studies using opening and closing plankton nets have given us snippets of information about vertical distributions, however, these are often restricted to a small geographic region or to only a few species.

Debbie, Mel and Hilary took a different approach, using a combination of museum collections to look at broad distributions and migration patterns, and shell geochemistry, to pinpoint exactly where shells are calcified.

Atlantid distribution findings

Species-collection data (species, depth, time) were collated from publications and from several museum collections. This revealed two patterns of atlantid heteropod vertical migration. Small species remained in shallow waters of <140 m at all times, whereas larger atlantids migrated to deep waters during the day and returned to shallow waters at night.

The data also revealed that some atlantids probably migrate to even deeper waters than anticipated (>600 m), highlighting that the atlantids may be affected by a shallowing aragonite lysocline (the depth in the ocean below which the rate of dissolution of calcite increases dramatically) in addition to surface-water acidification.

Shell calcification findings

When atlantids produce their shells they incorporate oxygen and carbon (and many other elements) from the water in which they live, trapping a chemical signature of the water within their shells. This chemical signature, in addition to water temperature and salinity, is used to determine the depth at which the atlantids calcified their shells.

To look closer at the depth of shell calcification, the team analysed oxygen isotope ratios of atlantid shells from the Atlantic Ocean, the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. The data revealed that calcification takes place within the upper 150 m of the water column for all 16 of the species analysed.

This depth is linked to concentration of chlorophyll (algae) in the water and is likely a region of abundant food. Atlantids are carnivorous, but their planktonic prey feed on algae and will have high numbers where there is abundant chlorophyll. This region is projected to experience the earliest and greatest anthropogenic ocean changes, strongly indicating that atlantid heteropods will be adversely affected in the near future.

Further information

You can read more in the article published in Marine Ecology Progress Series: Vertical distribution and diurnal migration of atlantid heteropods.

Contact

Contact Melanie Leng for more information.