Ammonites lived during the periods of Earth history known as the Jurassic and Cretaceous. Together, these represent a time interval of about 140 million years.

![Ammonites are the extinct relatives of sea creatures such as the modern Nautilus from Palau. By Manuae (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.bgs.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Nautilus_Palau.jpg)

Ammonites are the extinct relatives of sea creatures such as the modern nautilus. Image: Manuae

The Jurassic Period began about 201 million years ago and the Cretaceous Period ended about 66 million years ago. The ammonites became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous, at roughly the same time as the dinosaurs disappeared. However, we know a lot about them because they are commonly found as fossils formed when the remains or traces of the animal became buried by sediments that later solidified into rock.

The animal

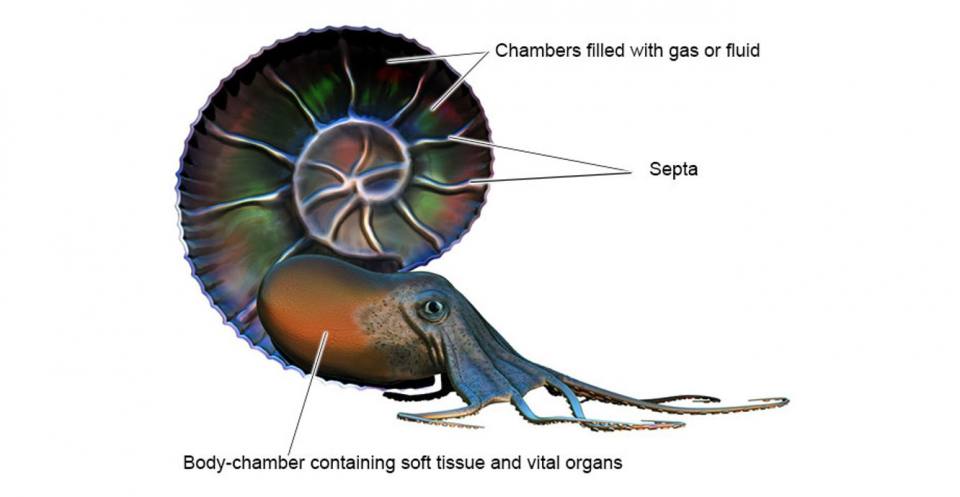

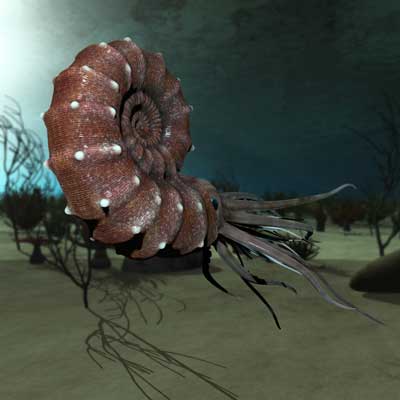

Ammonites were marine animals belonging to the phylum Mollusca and the class Cephalopoda. They had a coiled external shell similar to that of the modern nautilus. In other living cephalopods, e.g. octopus, squid and cuttlefish, the shells are small and internal, or absent.

An artist’s impression of a simplified cross-section through a ‘living’ ammonite. BGS (Chris Wardle) © UKRI.

The ammonite’s shell was divided into chambers separated by walls known as septa (singular: septum). These strengthened the shell and stopped it from being crushed by the external water pressure. Ammonites could probably not withstand depths of more than 100 m.

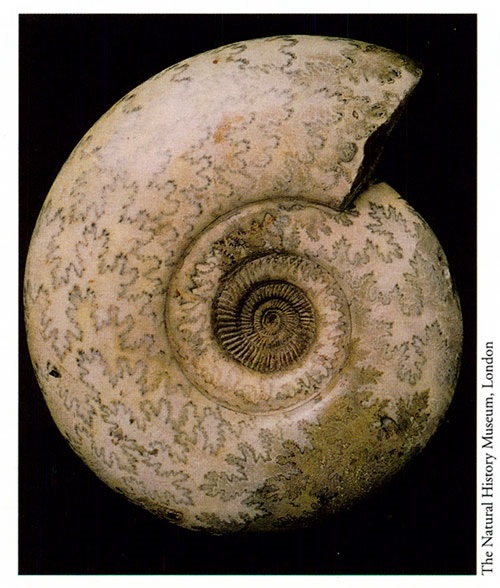

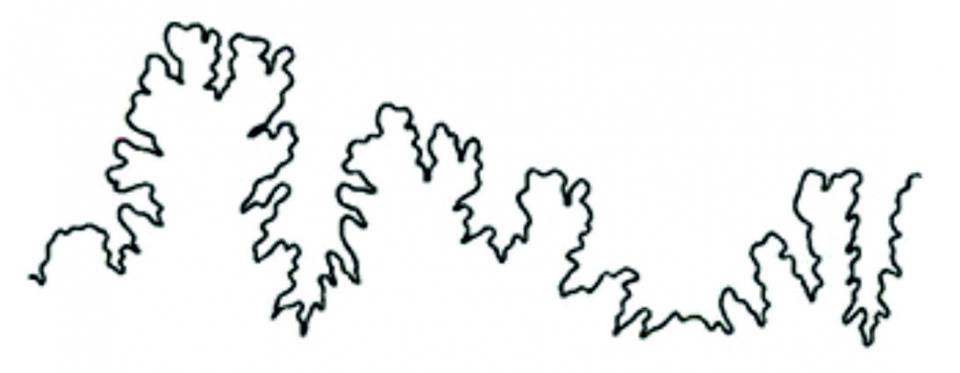

The septa had frilled edges. Intricate lines of varying complexity known as sutures mark where the septa joined the shell wall.

The ammonite itself lived in only the last chamber, the body-chamber; earlier chambers were filled with gas or fluid, which the ammonite was able to regulate in order to control its buoyancy and movement, much like a submarine.

Ammonites show an enormous range in size, from the very small to the height of a human. For example, the Late Jurassic Nannocardioceras is very small; complete adults are rarely more than 20 mm in diameter. At the other extreme, huge ammonites have been discovered; for example. Parapuzosia seppenradensis, from the Late Cretaceous, is 1.95 m in diameter. It was found in Germany in 1895. If complete, this specimen would have had a diameter of about 2.55 m.

The most important functions of the ammonite shell were protection and flotation.

Each complete 360° coil is called a whorl. Except for the innermost whorl, the shell is made up of three layers. The thin innermost and outermost layers are composed of prisms of aragonite (a form of calcium carbonate). The thicker middle layer is nacreous (mother-of-pearl), formed of tiny tabular crystals of aragonite.

In scientific literature, it has been the convention to illustrate ammonites with their body-chambers at the top. This is the opposite of their position in life.

Ribs, spines and tubercles (knobs), which frequently adorn the shell, may have strengthened it, but they may also have provided physical protection and camouflage against various predators, including marine reptiles (such as ichthyosaurs), crustaceans, fish and even other ammonites. They also helped to regulate buoyancy and stability, as well as being sexual display features.

Ammonites probably fed on small plankton, or vegetation growing on the sea floor. They may also have eaten slow-moving animals that lived on the sea bottom, such as foraminifera, ostracods, small crustaceans, young brachiopods, corals and bryozoa, as well as drifting, slow-swimming or dead sea creatures.

As with living animals, ammonites are classified into species and genera whose names must be Latin words or words that have been ‘Latinised’. The proper scientific name of any particular ammonite consists of the name of the species, preceded by the name of the genus to which it belongs, plus the name of the first person to describe it and the date it was first described.

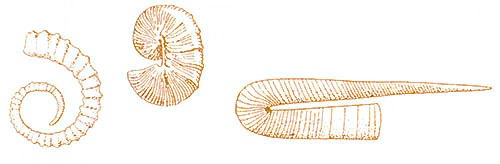

Some genera of ammonites had shells that were coiled in more bizarre ways than the usual spiral. These are known as heteromorphs, from the Greek heteros meaning ‘different’ and morphe meaning ‘form or shape’.

The coiled shell is generally the only part of the ammonite to be preserved as a fossil. As well as being aesthetically pleasing and popular with fossil collectors, they are of particular value to geologists.

The geologists’ tool

The use of ammonites in stratigraphy was pioneered in the 1850s by two Germans — Friedrich Quenstedt of Tübingen (1809–1889) and his one-time pupil, Albert Oppel of Munich (1831–1865). Their work was based on the ammonites of the Swabian and Franconian Alb of southern Germany — the eastern extension of the Jura Mountains of France and Switzerland, from which the Jurassic Period takes its name.

Friedrich Quenstedt (1809–1889). Courtesy of Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde, Stuttgart.

Albert Oppel (1831–1865). Courtesy of Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde, Stuttgart.

Guide fossils

Ammonites make excellent guide fossils for stratigraphy because:

- they evolved rapidly so that each ammonite species has a relatively short life span

- they are found in many types of marine sedimentary rocks

- they are relatively common and reasonably easy to identify

- they have a worldwide geographical distribution

The rapidity of ammonite evolution is the single most important reason for their superiority over other fossils for the purposes of correlation. Such correlation can be on a worldwide scale.

Ammonites can be used to distinguish intervals of geological time of less than 200 000 years’ duration. In terms of Earth history, this is very precise.

Ammonites through time

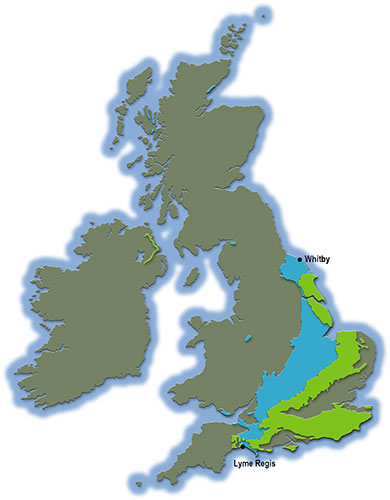

Map showing the main areas of Jurassic rocks (coloured blue) and Cretaceous rocks (coloured green) in Britain. The foreshore and cliffs at Lyme Regis and Whitby are famous collecting localities for ammonites and other fossils. BGS © UKRI.

Ammonite fossils are traditionally illustrated ‘upside down’ with the body chamber shown at the top. However, in life they would have swum the other way up.

Mantelliceras (Late Cretaceous, Cenomanian). BGS © UKRI.

Mantelliceras. Artist’s impression of living creature. BGS © UKRI.

Endemoceras (Early Cretaceous, Hauterivian). BGS © UKRI.

Endemoceras. Artist’s impression of living creature. BGS © UKRI.

Pavlovia (Late Jurassic, Kimmeridgian). BGS © UKRI.

Pavlovia. Artist’s impression of living creature. BGS © UKRI.

Stephanoceras (Mid Jurassic, Bajocian). BGS © UKRI.

Stephanoceras. Artist’s impression of living creature. BGS © UKRI.

Aegoceras (Early Jurassic, Pliensbachian). BGS © .

Aegoceras. Artist’s impression of living creature. BGS © UKRI.

Myths and legends

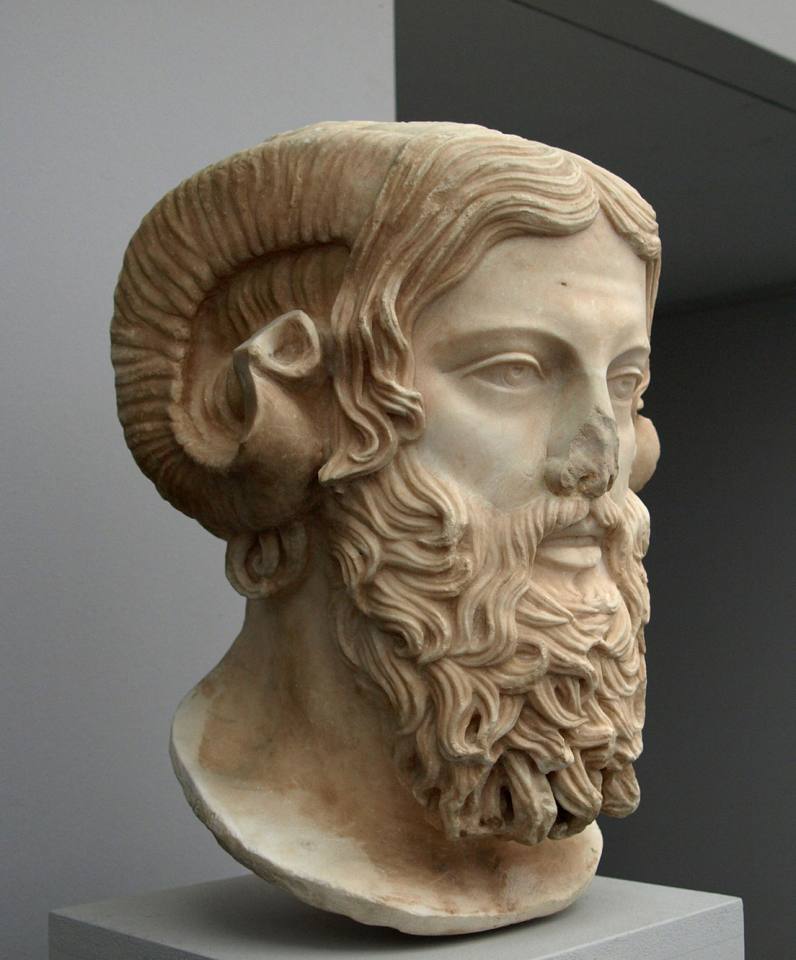

The ancient Greek god Zeus Ammon is depicted on coins from Cyrene (in modern day Libya) and in sculpture by a head with curling ram’s horns. Many genera of ammonites have names ending in –ceras from the Greek word ‘keras’ meaning horn.

Early works of natural history compared the coiled form of the ammonite with that of a serpent, and ammonites became widely known as snakestones. In order to perpetuate the legend that ammonites were serpents that had been turned into stone, local collectors and dealers in fossils frequently carved heads on them.

The snakestone legend is particularly associated with the town of Whitby in North Yorkshire, the home of the Anglo-Saxon abbess St Hilda (614–680 AD). The town’s coat-of-arms includes three ‘snakestones’. Used as charms, ammonites were thought to be a protection against serpents and a cure for baldness and infertility.

3D fossil models

Many of the fossils in the BGS palaeontology collections are available to view and download as 3D models. To view this fossil, or others like it, in 3D visit GB3D Type Fossils.

Derolytoceras radstockense (Early Jurassic, Pliensbachian). BGS © UKRI.

Reference

Cox, B M. 1995. Ammonites: fossil focus. (Nottingham, UK: British Geological Survey.)

You may also be interested in

Discovering Geology

Discovering Geology introduces a range of geoscience topics to school-age students and learners of all ages.

Fossils and geological time

Take a look at the history of the Earth, from its formation over four and a half billion years ago to present times.