The Chalk of the South Downs, like other limestone areas of the UK, hosts features indicative of a karst landscape, where drainage is underground through dissolutionally enlarged cavities, via features including:

- caves

- dolines

- dry valleys

- large springs

- solution pipes

- stream sinks

The Bedhampton and Havant spring complex in Hampshire is one of the best examples of Chalk karst springs in the UK. The springs are large, with a combined flow of approximately 104 000 m3/day (Atkinson and Smith, 1974) — enough to fill 40 Olympic-sized swimming pools every day. Such a high discharge is typical of karst springs fed by discrete open conduits.

Their karstic nature has also been demonstrated by tracer testing from stream sinks in the Horndean area to the springs (Atkinson and Smith, 1974; Barton et al., 1996). The springs are used as a drinking water source by Portsmouth Water Ltd.

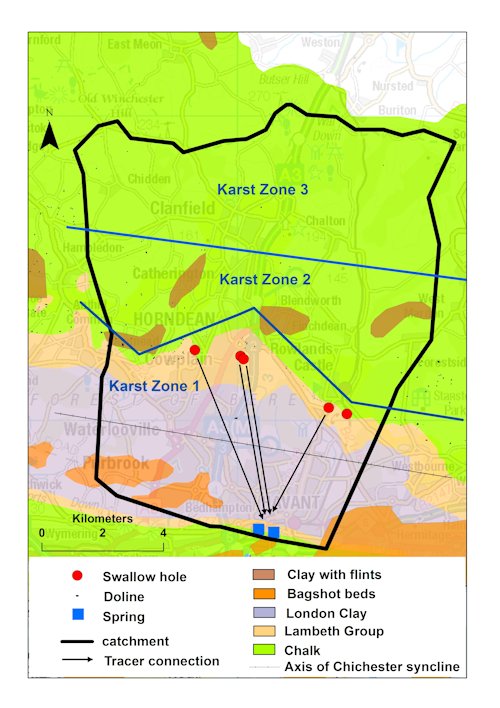

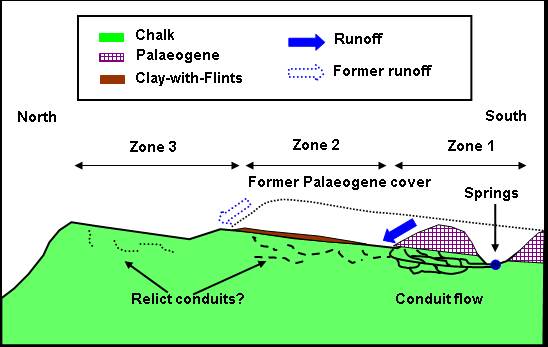

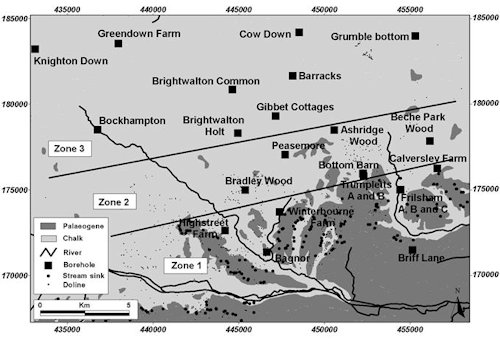

The geology, surface karst, and the total catchment area of the springs, based on the modelled drinking-water source protection zones, are shown in Figure 1. Figure 1 also divides the catchments into three ‘karst zones’ using the method developed by Maurice et al. (2006) in the Berkshire Chalk.

Figure 1 Geology and surface karst in the Bedhampton and Havant springs catchment. The catchment boundary is approximate and based on the SPZ-modelled total catchment. It differs slightly from the catchment boundary in Figure 5, which is based on a study by Day (1964). Geological material © NERC. All rights reserved. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown Copyright and database rights 2016.

The karst zones are defined on the basis of the geology as well as the density and type of surface karst features present. This is an overview of the karst hydrogeology in the catchment of the springs, based on available data for the catchment and current knowledge of the nature of Chalk karst in England.

Geology

The Bedhampton–Havant region is underlain by Upper Cretaceous-aged chalk and sands, silts and clays of Palaeogene age.

The Chalk Group comprises a soft, white, porous limestone, deposited between about 100 and 65 million years ago. It can be divided up into nine different formations, each characterised by differences in their physical characteristics (lithology) as well as the presence or absence of flint bands, marl seams, sponge beds and hardgrounds.

The Chalk is overlain by a sequence of Palaeogene sediments, 65 to 23 million years old. The oldest is the Lambeth Group, dominated by the clay-rich Reading Formation. This is overlain by the London Clay Formation. The youngest rocks in the region are the sands, silts and clays of the Bracklesham Group. These clay-rich units are impermeable and so support surface drainage.

Parts of the Chalk outcrop are covered in younger, superficial deposits including alluvium and the Clay-With-Flints Formation. The latter is a residual deposit derived from the weathering of the Palaeogene strata. As its name implies, it comprises a flinty clay, which can be several metres thick.

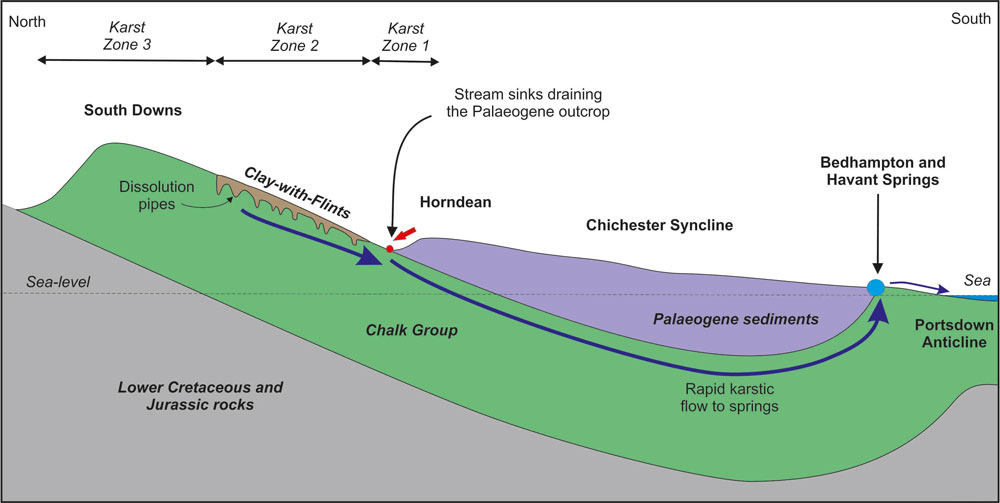

In this area, the rocks have been folded into a large, east–west-trending synclinal (trough) structure known as the Chichester Syncline. The Chalk of the South Downs dips southwards, disappearing beneath the overlying Palaeogene sediments, which are at the surface in the core of the syncline, before rising up to the surface along the Portsdown anticline (ridge) (Figure 2). The Bedhampton and Havant springs are found at the boundary between the Chalk and the overlying Lambeth Group, on the southern side of the Chichester Syncline.

Figure 2 Schematic cross-section across the Chichester Syncline showing the relationship of the geology to the underground drainage and karst features. (Not to scale.) BGS © UKRI.

Karst geomorphology

Several types of karst feature occur in the Bedhampton–Havant area.

Stream sinks

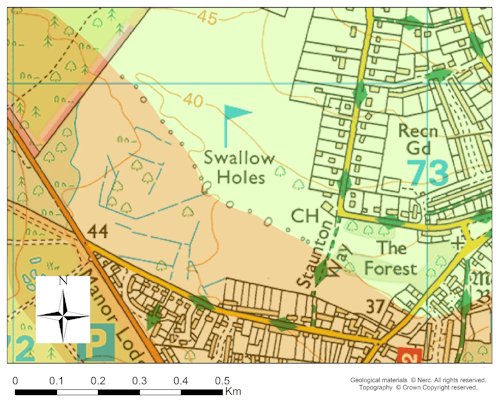

Stream sinks (also known as swallow holes) are surface karst features where water from surface streams sinks rapidly into the ground. In the Bedhampton–Havant area, they generally occur where drainage from the overlying Palaeogene clay-rich sediments sinks into the Chalk (Figure 3). Stream sinks are therefore concentrated along the boundary between these rocks at the surface, notably around Soberton Heath, Lovedean, Horndean and Rowlands Castle, where about 50 discrete sinks were reported (Barton et al., 1996). However, some of these may have been dolines and many of the hydrologically active stream sinks have been built over or culverted, so it is difficult to assess how many there were.

Figure 3 ‘Swallow holes’ shown on Ordnance Survey topographical maps along the Chalk (green)–Palaeogene (brown) boundary, west of Rowlands Castle. The features are not all hydrologically active. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown Copyright and database rights 2016.

Dolines

Dolines are depressions on the ground surface caused by the dissolution of the rocks beneath and can be common in the Chalk, especially in association with the Chalk–Palaeogene boundary. For example, in Dorset, up to 157 dolines per square kilometre are reported by Sperling et al. (1977). In the Bedhampton–Havant area, they appear to be locally common along the Chalk–Palaeogene boundary, and some are associated with stream sinks. Away from the boundary, dolines become progressively less common.

Dolines may be ancient stream sinks that are no longer active, or they may have been formed by other karst processes. For example, many dolines in the Chalk are likely to be formed by a process called ‘suffosion’, in which loose material such as soil, sand or silt is present above the Chalk and is gradually washed down into fissures within the Chalk itself. This causes the loose material to slump into these fissures, creating a depression at the surface.

Some dolines may have been infilled and others may have been dug deeper or wider by humans in the past to enable extraction of chalk for brickworks or lime. The presence of dolines is indicative of karst; however, it can be difficult to distinguish natural karst dolines from artificial chalk pits dug hundreds of years ago. Some surface depressions may be wrongly classified as dolines (Prince, 1964).

Solution pipes

Sediment-filled solution pipes can also be extremely common in the Chalk, especially beneath the Clay-With-Flints Formation (Waltham et al., 2005), so it is likely that these will be present in the Bedhampton–Havant area. These solution pipes can be up to 10 to 15 m deep, but have no surface expression (Figure 4).

Figure 4 A solution pipe in the Chalk beneath the Clay-With-Flints Formation, Marlborough, southern England. BGS © UKRI.

Karst zones

Using a method developed in the Pang–Lambourn catchments in Berkshire (Maurice et al., 2006), the catchment for the Bedhampton and Havant springs can be divided into three karst zones based on the distance from the Chalk–Palaeogene boundary (Figure 1).

- Karst zone 1 is characterised by frequent stream sinks and dolines associated with the boundary

- Karst zone 2 is an intermediate area where the Clay-With-Flints Formation is present (not shown on Figure 2). Dolines and solution pipes are likely to occur in this zone, but few hydrologically active stream sinks are present

- Karst zone 3 is the area furthest from the geological boundary, where stream sinks are absent and dolines are rare

Karst hydrogeology

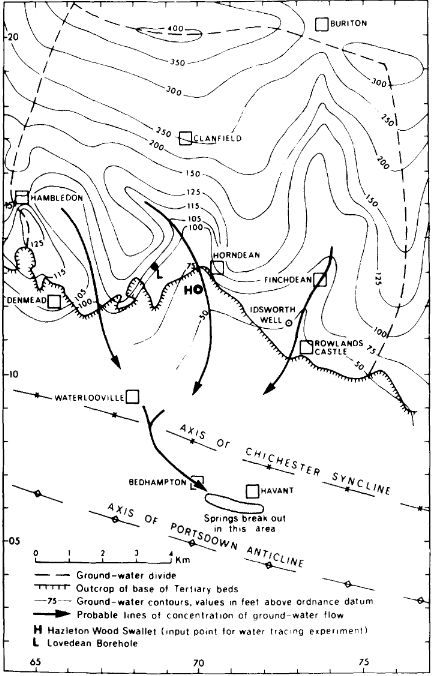

Groundwater contours indicate the elevation and gradient of the water table. Contours reported by Day (1964) suggest that the general flow direction within the catchment of the springs is from north to south, with focused concentrations of flow down valley features (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Groundwater flow in the catchments. (From Atkinson and Smith, 1974, based on Day, 1964.)

Tracer tests

Tracer tests can be used to determine connections between swallow holes and springs or boreholes, and to demonstrate how fast the water is moving in the subsurface. They involve tracing water as it moves through the subsurface by introducing a harmless substance, called a tracer, into the ground and sampling the water at springs or boreholes to detect the tracer.

Tracer tests have been carried out from five swallow holes located on the Chalk–Palaeogene boundary (Atkinson and Smith, 1974; Barton et al., 1996). Tracer from four of these swallow holes was detected at both the Bedhampton and Havant springs, demonstrating very rapid groundwater flow of several kilometres per day, based on time to first arrival of the tracer at the springs (Figure 1 and Table 1).

These velocities are extremely high and suggest flow through a well-connected system of karstic conduits and fissures extending over distances of many kilometres. The highest velocities of more than 10 km/day from the Rowlands Castle No. 39 swallow hole are substantially higher than the mean velocity of 1.94 km/day reported for 3015 tracer tests in karst aquifers by Worthington and Ford (2009).

The amount of tracer detected can also be used to calculate the proportion of injected tracer that has been recovered, which gives an indication of how much dilution or filtering of the tracer there has been. Atkinson and Smith (1974) reports tracer recoveries of 69.7 per cent for the test from Hazleton Wood swallow hole, which indicates relatively little loss of tracer along the flowpath, or relatively low dilution at the springs. Tracer recoveries were not reported for the tests by Barton et al. (1996).

A tracer test was also carried out from a swallow hole at Lovedean (#13) that demonstrated a connection with the Lovedean Well about 0.9 km away. The recorded velocity of 0.6 km/day was slower than those in the tracer tests from the swallow holes, but was still rapid.

| Injection site and number | Detection site | Distance (km) | Velocity (km/day) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazleton Wood/Horndean #32 | Bedhampton | 5.8 | 2.6 | Atkinson and Smith (1974) |

| Havant | 6.0 | 2.1 | Atkinson and Smith (1974) | |

| Lovedean #26 | Bedhampton | 6.3 | 2.7 | Barton et al. (1996) |

| Havant | 6.6 | 3.2 | Barton et al. (1996) | |

| Rowlands Castle #39 | Bedhampton | 4.8 | 10.5 | Barton et al. (1996) |

| Havant | 4.6 | 12.3 | Barton et al. (1996) | |

| Horndean #41 | Bedhampton | 5.8 | 9.1 | Barton et al. (1996) |

| Havant | 5.7 | 4.0 | Barton et al. (1996) | |

| Lovedean #13 | Lovedean Well | 0.9 | 0.6 | Barton et al. (1996) |

| Rowlands Castle #40 | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected | Barton et al. (1996) |

The tracer tests demonstrate the presence of karstic groundwater flow linking the stream sinks along the Chalk–Palaeogene boundary to the springs in the southerly parts of the catchments. The nature of karst in the Chalk for the more northern parts of the catchments is more difficult to define as there have been no studies of it there.

Transmissivity

Other measurements of the rate at which water flows through the rock (‘transmissivity’) can be used to indicate where solutional fissures and conduits may be occurring, as high transmissivity is likely to indicate their presence. However, there are no transmissivity records within the catchment. The nearest transmissivity measurements (Allen et al., 1997) are 10 to 20 km to the east and are highly variable. They include fairly low (57 m2/day) and very high (9100 m2/day) values within karst zone 2 (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Transmissivity data in the area to the east of the Bedhampton–Havant catchment. Geological material © NERC. All rights reserved. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown Copyright and database rights 2016.

Karst zones 2 and 3 in other Chalk areas

Several studies in other areas of the Chalk in England provide insight into the nature of karst in areas away from the Palaeogene outcrop. Some have demonstrated the presence of connected karstic conduits and fissures in karst zones 2 and 3.

The Pang and Lambourn catchments in Berkshire are in a similar geological setting to the Bedhampton and Havant springs catchment and therefore provide a useful comparison.

A study in these catchments by Maurice et al. (2006) provides a description (conceptual model) of one mechanism that could result in conduit development in areas away from the Chalk–Palaeogene boundary. Most Chalk stream sinks are currently located at or close to this boundary and are generally absent in karst zones 2 and 3. However, through geological time, this geological boundary has progressively moved and, in the past, a greater area of the Chalk would have been covered by Palaeogene strata and the Clay-With-Flints Formation before the material was eroded, as illustrated in Figure 7.

The conceptual model suggests that swallow holes may have been present in areas to the north of the current Chalk–Palaeogene boundary. Any underground conduits or dissolutionally enlarged fractures associated with them may still be present.

Another study in the Pang and Lambourn catchments used a type of tracer test known as a single borehole dilution test (SBDT) with the specific aim of investigating subsurface karst in areas away from the Chalk–Palaeogene boundary (Maurice et al., 2012). SBDTs provide information on the location and numbers of actively flowing features (fissures and fractures) intercepted by boreholes.

In this study, SBDTs were conducted in 26 boreholes (Figure 8). Flowing features were detected in boreholes in all three karst zones. The density of flowing features identified from the SBDTs decreased from 0.25 features per metre of borehole in karst zone 1, to 0.18 per metre in karst zone 2, to 0.15 per metre in karst zone 3. However, topography appeared to influence the density of flowing features, with higher densities in river valleys and major dry valleys, including the highest densities, which were in major dry valleys in karst zone 3 (Table 2).

Camera images were obtained from three boreholes in karst zones 2 and 3, which revealed that the flow horizons identified from the SBDTs were conduits up to about 15 cm in diameter, or solutional fissures. At one borehole in karst zone 3, sediment-filled solution features were observed at 74 m below sea level, indicating a connected system of conduits and fissures of sufficient size to transport sediment from the surface.

Overall, this study showed that there can be conduits and fissures present in boreholes in karst zones 2 and 3 that enable rapid dilution of tracer in SBDTs. It also shows that these features occur more frequently in karst zone 1, river valleys and dry valleys throughout all karst zones.

Table 2 The density of flowing features identified from SBDTs in the Pang and Lambourn catchments (number per metre). (From Maurice et al., 2012.)

| River valley | Major dry valley | Interfluve and minor dry valley | All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.25 ± 0.09 | – | 0.26 ± 0.28 | 0.25 ± 0.07 |

| 2 | – | 0.26 ± 0.32 | 0.14 ± 0.10 | 0.18 ± 0.09 |

| 3 | 0.17 | 0.41 | 0.10 ± 0.14 | 0.15 ± 0.14 |

| All | 0.23 ± 0.08 | 0.29 ± 0.20 | 0.15 ± 0.07 | 0.20 ± 0.05 |

There have been a few catchment-scale tracer studies of Chalk karst in the equivalent of karst zones 2 and 3. A tracer test has been conducted in karst zone 2 in Hertfordshire: tracer injected into a soakaway that drains into the Chalk was detected about 3 km away, demonstrating rapid groundwater flow of 2 km/day combined with high tracer losses (Price et al., 1992). Two unpublished studies in different areas of Chalk in East Anglia in the equivalent of karst zone 3 both indicated velocities of approximately 0.1 km/day over distances of up to 1.5 km, again combined with very high tracer losses.

These tracer studies suggest that rapid groundwater flow can occur over substantial distances in karst zones 2 and 3, but that a substantial proportion of the tracer was dispersed and diffused into the rock matrix and fractures surrounding the karstic conduit or fissure systems. This tracer may have been stored and then gradually released, but the timescales for this are unknown.

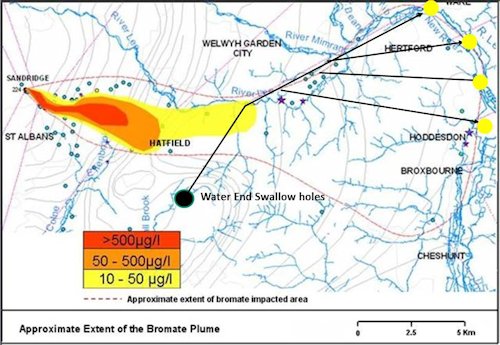

A large plume of a chemical contaminant (bromate) that originated at Sandridge in the Hertfordshire Chalk, in the equivalent of karst zone 2, has intersected a karst conduit system fed by the Water End Swallow Holes (Figure 9). The presence of the conduit system was demonstrated by tracer tests from the Water End Swallow Holes to springs and boreholes up to 20 km to the east, in the equivalent of karst zone 1 (Harold, 1937; Cook et al., 2012). The bromate is present in these springs and boreholes; the bromate plume has created an ‘accidental’ tracer test illustrating connectivity between Chalk groundwater in karst zone 2 and conduit systems in karst zone 1.

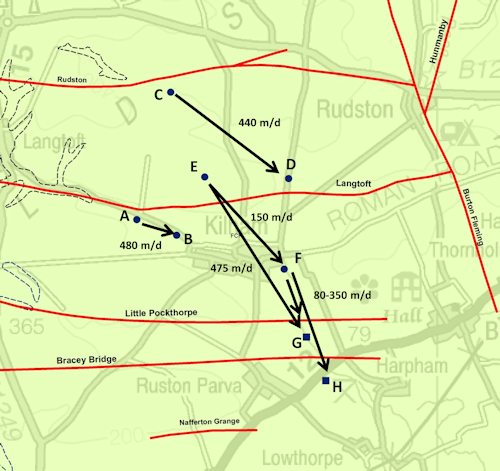

A series of tracer tests was also carried out in the Chalk in Yorkshire, in the Kilham area (Ward et al., 1997). There are no stream sinks or dolines reported in this area where the geological setting is different, and there are no Palaeogene deposits overlying the Chalk. The Chalk is also substantially harder and more fractured in the Yorkshire Wolds.

Tracer testing was carried out from monitoring boreholes and demonstrated rapid groundwater flows of up to 0.48 km/day over distances of several kilometres (Figure 10). These tests demonstrate that even in areas where surface karst is absent (equivalent to karst zone 3) there can be rapid groundwater flow through connected networks of solutional conduits and fissures over distances of several kilometres.

Conclusions

The Bedhampton and Havant karst springs have been proven to be connected to karstic stream sinks located along the Chalk–Palaeogene boundary, in karst zone 1. It is also likely that connected networks of dissolutionally enlarged fissures and conduits are present within karst zones 2 and 3 and contribute to the spring discharge. Whilst it may be more likely that they occur beneath the dry valleys, the location of such networks is not known and they may occur less frequently than in karst zone 1.

Further reading

Allen, D J, Brewerton, L J, Coleby, L M, Gibbs, B R, Lewis, M A, MacDonald, A M, Wagstaff, S J, and Williams, A T. 1997. The physical properties of the major aquifers in England and Wales. British Geological Survey Technical Report WD/97/34; Environment Agency R&D Publication 8.

Atkinson, T C, and Smith D I. 1974. Rapid groundwater flow in fissures in the Chalk: an example from south Hampshire. Quarterly Journal of Engineering Geology 7, 197–205. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.QJEG.1974.007.02.05

Barton, M E, Cater, R, and Price, N J. 1996. The Chalk swallow holes of south-east Hampshire: geological setting, groundwater hazards and fissure flow rates. Geological Society, 65–72.

Cook, S J. 2010. The hydrogeology of bromate contamination in the Hertfordshire Chalk: incorporating karst in predictive models. Unpublished PhD thesis, University College London.

Cook, S J, Fitzpatrick, C M, Burgess, W G, Lytton, L, Bishop, P, and Sage, R. 2012. Modelling the influence of solution-enhanced conduits on catchment-scale contaminant transport in the Hertfordshire Chalk Aquifer. Geological Society Special Publication 364, 205–225. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1144/SP364.14

Day, J B W. 1964. Infiltration into a groundwater catchment and the derivation of evaporation. Water Supply Papers of the Geological Survey of G.B. Research Report No 2.

Harold, C. 1937. The flow and bacteriology of underground water in the Lee Valley. Metropolitan Water Board 32nd Annual Report, 89–99.

Maurice, L, Atkinson, T C, Barker, J A, Bloomfield, J P, Farrant, A R, and Williams, A T. 2006. Karstic behaviour of groundwater in the English Chalk. Journal of Hydrology, Vol. 330(1–2), 63–70. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2006.04.012

Maurice, L D, Atkinson, T C, Barker, J A, Williams, A T, and Gallagher, A. 2012. The nature and distribution of flowing features in a porous limestone aquifer with small-scale karstification. Journal of Hydrology, Vol. 438–439, 3–15. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2011.11.050

Price, M, Atkinson, T C, Barker, J A, Wheeler, D, and Monkhouse, R A. 1992. A tracer study of the danger posed to a chalk aquifer by contaminated highway run-off. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers: Water, Maritime, & Energy, Vol. 96, 9–18. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1680/iwtme.1992.09754

Prince, H C. 1964. The origin of pits and depressions in Norfolk. Geography 49(1), 15–32.

Sperling, C H B, Goudie, A S, Stoddart, D R, and Poole, G G. 1977. Dolines of the Dorset chalklands and other areas in southern Britain. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, Vol. 2(2), 205–223.

Waltham, T, Bell, F G, and Culshaw, M G. 2005. Sinkholes and Subsidence: Karst and Cavernous Rocks in Engineering and Construction. (Berlin, Germany: Springer-Praxis Books in Geophysical Sciences). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/b138363

Ward, R S, Williams, A T, and Chadha, D S. 1997. The use of groundwater tracers for assessment of protection zones around water supply boreholes — a case study. 369–376 in Tracer Hydrology. Kranjc, A (editor). Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Water Tracing. (London, UK: CRC Press.)

Worthington, S R H, and Ford, D C. 2009. Self-organised permeability in carbonate aquifers. Groundwater, Vol. 47(3), 326–336. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6584.2009.00551.x

Need more information?

Find out more about our research

Karst aquifers

Aquifers formed in the Chalk Group and the Jurassic and Permian limestones of England.

Karst features

The distinctive features of karst landscapes.

Karst report series

An overview of the evidence for karst in the Chalk and Jurassic and Permian limestones in different areas of England.

What causes sinkholes?

Explore the different types of sinkhole encountered in the UK.

Sinkholes research

Our research extends beyond the distribution and processes associated with sinkhole formation to the broader subject of karst.