From January 2016 to February 2020, the universities of York and Manchester were together monitoring air quality and greenhouse gases at the proposed Third Energy shale gas exploration site in Kirby Misperton. As well as capturing meteorological information, the monitoring equipment was set up to measure concentrations of:

- ozone (O3)

- particulate matter (PM1, PM2.5, PM4, and PM10)

- nitrogen oxides (NO, NO2 and NOx)

- methane (CH4)

- non-methane hydrocarbons (NHMCs)

- hydrogen sulfide (H2S)

- carbon dioxide (CO2)

Figure 1 Air quality monitoring equipment at the Kirby Misperton site. BGS © UKRI.

Rationale for monitoring

In the context of hydrocarbon exploration and production, atmospheric emissions have a number of potential effects. Emissions may have, both separately and collectively, implications for climate change, air quality and public and occupational health.

Public health

These parameters concern direct primary emissions from infrastructure onsite such as particulate matter and NO2 from:

- generators

- traffic

- plant

- flares

- dust

- materials handling

There are also gases that may affect air quality, such as NMHCs and potentially hazardous and harmful trace gases such as benzene (C6H6).

Secondary effects may occur downwind through reactive chemistry. Unlike greenhouse gases, many of the species mentioned are regulated both for emissions and in ambient air.

Greenhouse gases

Wide variations in the concentration of these gases occur over various timescales as a result of uptake by plants and variations in anthropogenic emissions. Variations can be seen for even minor changes in wind direction, depending on local conditions (for example, if a road exists nearby). Monitoring of gases over time therefore provides an understanding of the baseline, to which any changes induced by future activity can be compared quantitatively.

There are numerous sources of greenhouse gases, both natural and artificial. Natural variations of long-lived greenhouse gases, mainly CH4 and CO2, relate to soil and deeper subsurface processes. This signal is augmented by fugitive emissions from vehicle exhausts, industry and landfill. Development of a shale gas exploration programme potentially adds further fugitive emissions from leaks, gas storage, processing operations, fracking fluid and flowback. It is important to establish the range of baseline concentrations of greenhouse gases and other air quality parameters before any shale gas operations begin.

The monitoring site

The monitoring site (Figure 1) was located within the boundary of the Third Energy site. The station consisted of a waterproof enclosure installed with instrumentation to measure continuous concentrations of O3, PMs, NOx, CH4 and CO2, as well as wind speed and direction, air temperature and relative humidity. In addition, air samples were taken in stainless steel canisters and returned to the University of York for analysis of a wider range of parameters.

Data interpretation

Meteorology

Data for the first few months of wind measurement are shown in Figure 2. This shows that over the winter of 2015 to 2016, the dominant wind direction was from the south west quadrant (about 40 per cent), which is also the direction from which the strongest winds were observed. This is consistent with the series of vigorous Atlantic storms experienced over that winter.

Figure 2 Wind rose showing wind speed and direction statistics for the period January 2016 to 10 March 2016. The radius defines the percentage of time the wind in each of 12 wind direction cones (30° span), while the colour scale defines the wind speed (red colours indicating strong wind speeds over 6 ms-1 and yellow colours indicating lighter winds).

Greenhouse gases

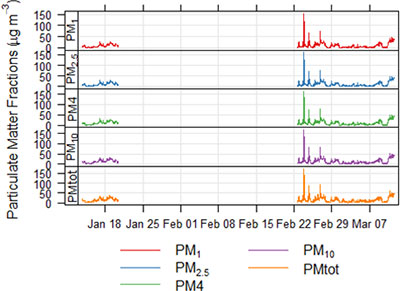

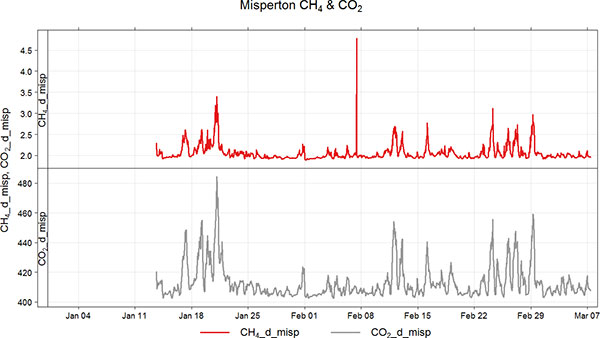

Greenhouse gas concentrations have been measured from 13 January 2016. A time series of the data is shown in Figure 3. A general correlation between CO2 and CH4 can be seen over the measurement period. Concentrations above the background are seen for every wind direction but with a greater tendency when the wind is from the south-west (albeit for the very limited dataset).

Figure 3 Time series of methane (red) and carbon dioxide (grey) concentrations in air. Units are parts per million (ppm). BGS © UKRI.

Air quality

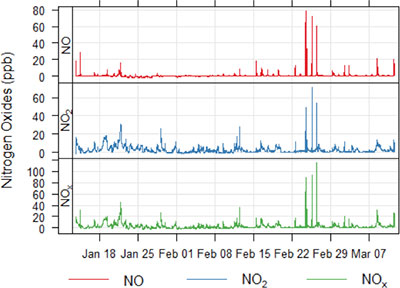

The time series for O3, NO, NO2, NOx, PM1, PM2.5, PM4 and PM10 are shown in figures 4, 5 and 6. The data gap in the PM measurement is due to an instrument problem. The data indicates that there are times when the site is affected by higher levels of pollution in the form of NO, NO2 and particles (spikes on the graphs). These are likely to reflect emissions from vehicle movements near the site.

Measurement statistics

The concentration statistics for the range of parameters are shown in Table 1. Although there is only a limited dataset, the mean concentration of CH4 is similar to the northern hemispheric seasonal average of around 1.9 ppm, while the CO2 site average is marginally enhanced relative to this wintertime hemispheric average (around 402 ppm).

Table 1 Statistical metrics for air-quality pollutants. Percentages refer to percentiles. LOD refers to measurements below the limit of detection of the instrument.

| Compund | Unit | 10% | 25% | 33% | Mean | 75% | 90% | 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH4 | ppm | 1.94 | 1.96 | 1.97 | 2.06 | 2.08 | 2.26 | 2.45 |

| CO2 | ppm | 404.73 | 405.93 | 406.92 | 412.97 | 414.30 | 428.40 | 439.25 |

| O3 | ppb | 13.36 | 21.35 | 23.93 | 28.92 | 34.01 | 38.44 | 40.53 |

| NO | ppb | LOD | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.27 | 0.83 | 1.66 |

| NO2 | ppb | LOD | 0.37 | 0.63 | 1.27 | 2.61 | 4.97 | 6.54 |

| NOx | ppb | LOD | 0.41 | 0.68 | 1.41 | 2.92 | 5.51 | 7.86 |

| PM1 | μg/m3 | 1.17 | 2.17 | 2.92 | 5.19 | 13.10 | 23.53 | 29.71 |

| PM2.5 | μg/m3 | 1.78 | 3.08 | 3.87 | 6.57 | 14.49 | 24.94 | 31.76 |

| PM4 | μg/m3 | 2.28 | 3.86 | 4.84 | 7.79 | 15.66 | 26.00 | 33.15 |

| PM10 | μg/m3 | 2.79 | 4.55 | 5.80 | 8.98 | 17.68 | 27.85 | 34.83 |

| PMtotal | μg/m3 | 3.17 | 5.34 | 6.75 | 10.29 | 19.75 | 30.78 | 38.26 |

| Particle count | particles/cm3 | 28.83 | 57.92 | 78.73 | 154.20 | 407.60 | 573.96 | 682.93 |

Non-methane hydrocarbons results

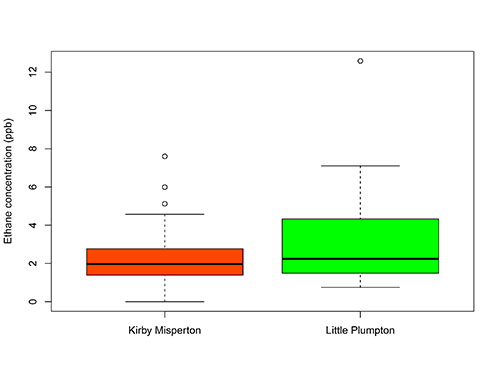

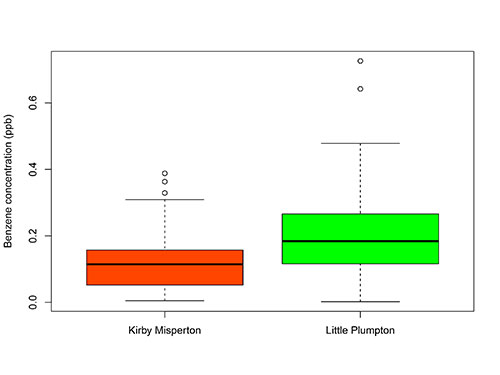

Samples for hydrocarbon (C2 to C6) analysis were collected weekly in special canisters from both the Little Plumpton (Lancashire) and Kirby Misperton (Yorkshire) sites and returned to the WACL laboratory at the University of York’s Wolfson Atmospheric Chemistry Laboratories.

The plots in figures 7, 8 and 9 show the distribution of individual species (ethane, propane and benzene) at the Kirby Misperton and Little Plumpton sites (Kirby Misperton: 87 samples from November 2015 to August 2017; Little Plumpton: 65 samples from October 2015 to August 2017). The dataset for hydrocarbons from 2016 is available on the BADC website archive.

Figure 7 Box plots showing the distributions of ethane from Kirby Misperton and Little Plumpton. BGS © UKRI.

Figure 8 Box plots showing the distributions of propane from Kirby Misperton and Little Plumpton. BGS © UKRI.

Figure 9 Box plots showing the distributions of benzene from Kirby Misperton and Little Plumpton. BGS © UKRI.

Note: EC Air Quality Directive limit value for benzene (annual mean) = 1.54 ppb. Observations to date indicate a median baseline concentration around a factor of ten lower than the EC directive limit value.