Stream sinks (also known as swallow holes) are points at which water sinks directly into the ground. In some cases they may be associated with a surface depression; in others they may just be focused points within a stream bed where water disappears into the ground. They are distinguished from dolines (sinkholes) by their hydrologically active nature, although many are ephemeral and do not flow constantly.

A chalk stream sink, southern England. BGS © UKRI.

Karst stream sinks occur relatively frequently in the Chalk, Jurassic limestone and Permian limestone. Stream sinks are often associated with geological boundaries where there are lower-permeability deposits overlying the karstic rock. Surface run-off forms streams or rivers on the lower-permeability deposits, which then sink into the underlying karst at or close to the geological boundary.

Chalk stream sinks have been most extensively mapped, which has revealed that they can have very high densities along the boundary between the Chalk and the overlying Palaeogene clays and sands. For example, more than 130 stream sinks have been mapped in the Pang and Lambourn catchments in Berkshire (Maurice et al., 2006). Whilst individually these Chalk stream sinks have relatively small flows, ranging from small seeps to streams with flows of several litres per second following rainfall, collectively they form an important contribution to recharge and provide a direct flow path into the aquifer.

Dolines (also known as sinkholes) are surface depressions that are formed by solution processes and are not associated with a stream. They are formed by natural processes, unlike some surface depressions that are often called ‘sinkholes’ but are actually formed by collapse into artificial cavities.

They are generally classified as solution dolines, collapse dolines or subsidence dolines. Dolines may be palaeokarst features that are not currently hydrologically active. However, they are genetically karstic and their presence implies that there is or has been a fully connected flow path between the doline and the aquifer discharge point, enabling transport of solute and/or sediment through the aquifer (Williams, 2004).

Dolines are present in the Chalk and the Jurassic and Permian limestones, where they are usually smaller than dolines in Carboniferous limestone. However, one of the most famous karst dolines in the UK is Culpeppers Dish in the Chalk in Dorset, which is 21 m deep and 86 m in diameter. Doline densities in Dorset can be more than 100/km2, which is comparable to those in the South Wales Carboniferous limestone (Sperling et al., 1977). In some areas, it can be difficult to distinguish dolines from artificial pits that may have a similar shape.

Solution pipes are subsurface solutional voids that are filled with sediment. They may occur with no surface expression and they are often filled with low-permeability material, so they do not provide a rapid pathway to the subsurface. They are frequently encountered in engineering works, especially in the Chalk (Edmonds, 2008) and are indicative that karst processes are occurring in the area.

Solution pipe at Bempton Cliffs, Yorkshire. © Derek Gobbet, Hull Geological Society.

Small conduits from a few to tens of centimetres in diameter are revealed in quarries and on images of borehole walls. Although they are quite small in size, water can move rapidly through them.

Chalk karst conduits, 10 to 20 cm in diameter, intercepted in Swanscombe Quarry, Kent.

In karst studies, high temporal resolution discharge and water-quality data are used to assess the nature of karst. A higher degree of karstification is associated with springs that have rapid responses to precipitation resulting in changes in discharge and chemistry over periods of hours or days (Shuster and White, 1971; White, 1988).

Large springs (more than 10 l/s, and especially those more than 100 l/s) in themselves are indicative of karst processes, as a connected network of solutional voids of sufficient size is required to sustain the discharge.

Lynchwood ephemeral chalk spring, Lambourn, southern England. Flow varies seasonally from 0 to approximately 700 l/s. BGS © UKRI.

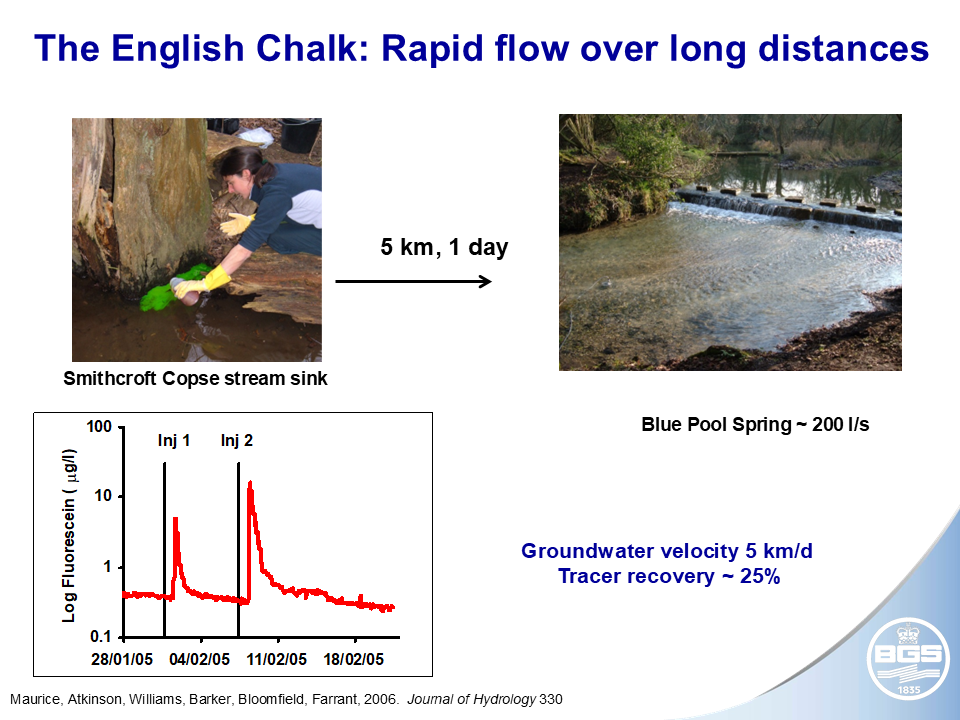

Successful tracer tests demonstrate the location of rapid karstic groundwater flow paths. Testing in the Chalk and the Jurassic limestone has demonstrated groundwater velocities of several kilometres per day over distances of several kilometres (for example, Atkinson and Smith, 1974; Banks et al., 1995; Foley et al., 2012).

One example is a tracer test in Berkshire, which involved injecting only a few hundred millilitres of a sodium fluourescein dye solution into a stream sink (Maurice et al., 2006). The tracer arrived five kilometres away at the Blue Pool spring in just 24 hours, illustrating how vulnerable these aquifers can be to pollution.

Tracer test in the Chalk, Berkshire. BGS © UKRI.

Tracer test in the Chalk, Berkshire. BGS © UKRI.

Karst aquifers are often characterised by high incidences of microbial pollutants, which often occur following recharge events. The presence of microbial contaminants in boreholes and springs is indicative of short residence-time groundwater, as some microbial contaminants only persist in aquifers for one to two weeks. Increased turbidity in springs and boreholes following rainfall can also be indicative of karst flow paths.

Atkinson, T C, and Smith, D I. 1974. Rapid groundwater flow in fissures in the Chalk: An example from South Hampshire. Quarterly Journal of Engineering Geology, Vol. 7. 197–205. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.QJEG.1974.007.02.05

Banks, D, Davies, C, and Davies, W. 1995. The Chalk as a karstic aquifer: evidence from a tracer test at Stanford Dingley, Berkshire, UK. Quarterly Journal of Engineering Geology, Vol. 28(1), S31–S38. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1144/GSL.QJEGH.1995.028.S1.03

Edmonds, C. 2008. Improved groundwater vulnerability mapping for the karstic Chalk aquifer of south east England. Engineering Geology, Vol. 99(3–4), 95–108. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2007.11.019

Foley, A, Cachandt, G, Franklin, J, Willmore, F, and Atkinson, T. 2012. Tracer tests and the structure of permeability in the Corallian limestone aquifer of northern England, UK. Hydrogeology Journal, Vol. 20, 483–498. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-012-0830-x

Maurice, L D, Atkinson, T A, Barker, J A, Bloomfield, J P, Farrant, A R, and Williams, A T. 2006. Karstic behaviour of groundwater in the English Chalk. Journal of Hydrology, Vol. 330, 53–62. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2006.04.012

Shuster, E T, and White, W B. 1971. Seasonal fluctuations in the chemistry of limestone springs: a possible means for characterising carbonate aquifers. Journal of Hydrology, Vol. 14, 19–128. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1694(71)90001-1

Sperling, C H B, Goudie, A S, Stoddart, D R, and Poole, G G. 1977. Dolines of the Dorset chalklands and other areas in southern Britain. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, Vol. 2, 205–223. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/621858

White, W B. 1988. Geomorphology and Hydrology of Karst Terrains. (Oxford University Press.) ISBN: 9780195044447

Williams, P. 2004. Dolines. 304–310 in Encyclopaedia of Caves and Karst Science. Gunn, J (editor). ISBN: 9781579583996

Need more information?

Find out more about our research

Karst aquifers

Aquifers formed in the Chalk Group and the Jurassic and Permian limestones of England.

Karst hydrogeology of the Bedhampton and Havant springs

One of the best examples of Chalk karst springs in the UK.

Karst report series

An overview of the evidence for karst in the Chalk and Jurassic and Permian limestones in different areas of England.

What causes sinkholes?

Explore the different types of sinkhole encountered in the UK.

Sinkholes research

Our research extends beyond the distribution and processes associated with sinkhole formation to the broader subject of karst.